A Classic Album That Turned Nashville’s Honky-Tonk Confessions into Timeless Poetry

In 1971, when country music was balancing tradition with a growing hunger for introspection, Kris Kristofferson delivered an album that would define not only his career, but the emotional vocabulary of outlaw country itself. The Silver Tongued Devil and I was his second studio album, and its title track quickly became one of the most revealing self-portraits ever written in Nashville.

More than half a century later, “The Silver Tongued Devil and I” still resonates—not because it shouts, but because it confesses. It is a song of quiet internal warfare, of longing wrapped in wit, of charm imagined rather than possessed. It is also a snapshot of Nashville’s Music Row at a time when ambition and insecurity shared the same barstool.

Nashville, Music Row, and the Tally-Ho Tavern

Before Kristofferson became one of country music’s most respected songwriters, he was a struggling artist trying to break through in Nashville. Music Row—lined with publishing houses, studios, and smoky taverns—was both opportunity and obstacle. It was here that dreams were born, crushed, and occasionally immortalized.

The Tally-Ho Tavern, referenced in the song, was a real bar and a genuine part of Kristofferson’s life. He reportedly worked there as a bartender, serving drinks to the very songwriters and musicians he would later stand beside as an equal. That lived experience gives “The Silver Tongued Devil and I” its authenticity. This isn’t imagined heartbreak—it’s observed insecurity, distilled into melody.

The Song as a Character Study

“The Silver Tongued Devil and I” unfolds like a short story. The narrator sits at a bar, eyeing a “tender young maiden.” He wants to speak, to charm, to seduce with confidence. But instead, he battles himself.

The “silver tongued devil” is not another man—it’s his alter ego. It represents the bold, smooth-talking version of himself he wishes he could be. The devil is persuasive, fearless, and magnetic. The narrator, by contrast, is hesitant, introspective, and painfully aware of his limitations.

This duality—between who we are and who we wish we were—is central to Kristofferson’s writing. His characters rarely present themselves as heroes. Instead, they are flawed, vulnerable, and human. In this sense, the song is less about romantic pursuit and more about identity.

It asks a quiet but powerful question: Who is really in control—our conscience or our cravings?

The Sound of Smoke and Solitude

Musically, the track is deceptively simple. A steady rhythm section, understated instrumentation, and Kristofferson’s unmistakable baritone voice create an atmosphere thick with late-night reflection. You can almost hear the glasses clink and the low hum of barroom conversation.

Unlike the dramatic orchestration that dominated some country productions of the era, Kristofferson kept it grounded. The minimalism serves the story. There’s no need for grand crescendos—the drama exists entirely within the narrator’s internal dialogue.

His vocal delivery is conversational yet poetic. He doesn’t oversing. He doesn’t perform emotion; he inhabits it. That restraint became one of his signatures and helped separate him from the polished Nashville mainstream.

A Mirror of the Outlaw Movement

Though the full outlaw country wave would crest later in the 1970s, Kristofferson was already laying its foundation. Artists like Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson would soon push back against Nashville’s rigid commercial system, demanding creative control and raw authenticity.

Kristofferson’s songwriting embodied that rebellion—not through volume, but through vulnerability. “The Silver Tongued Devil and I” rejected the glossy love-song formula. Instead of triumphant romance, we get awkward hesitation. Instead of bravado, we get self-doubt.

That honesty was revolutionary.

The Album’s Wider Impact

The album The Silver Tongued Devil and I also featured some of Kristofferson’s most enduring compositions, including “Loving Her Was Easier (Than Anything I’ll Ever Do Again).” Together, the songs created a thematic tapestry of longing, regret, temptation, and emotional complexity.

By this point, Kristofferson had already written hits recorded by others, including Johnny Cash and Janis Joplin. But this album solidified him not just as a songwriter-for-hire, but as an artist with a distinct voice and philosophical depth.

Critics praised the album for its literary quality. Kristofferson, a Rhodes Scholar and former Army officer, brought intellectual nuance to country music without sacrificing grit. His lyrics were poetic but never pretentious. He understood the barroom because he had lived in it.

Why the Song Still Matters

More than five decades later, “The Silver Tongued Devil and I” continues to feel modern. In an age of curated personas and social media bravado, the idea of wrestling with an internal “devil” feels especially relevant.

We all carry versions of ourselves—the confident one, the cautious one, the reckless one. Kristofferson gave that internal conflict a melody and a name.

The genius of the song lies in its relatability. You don’t have to sit in a Nashville tavern to understand it. Anyone who has ever hesitated before speaking their heart knows the tension. Anyone who has ever imagined a braver version of themselves understands the silver-tongued devil whispering suggestions.

Kristofferson’s Enduring Legacy

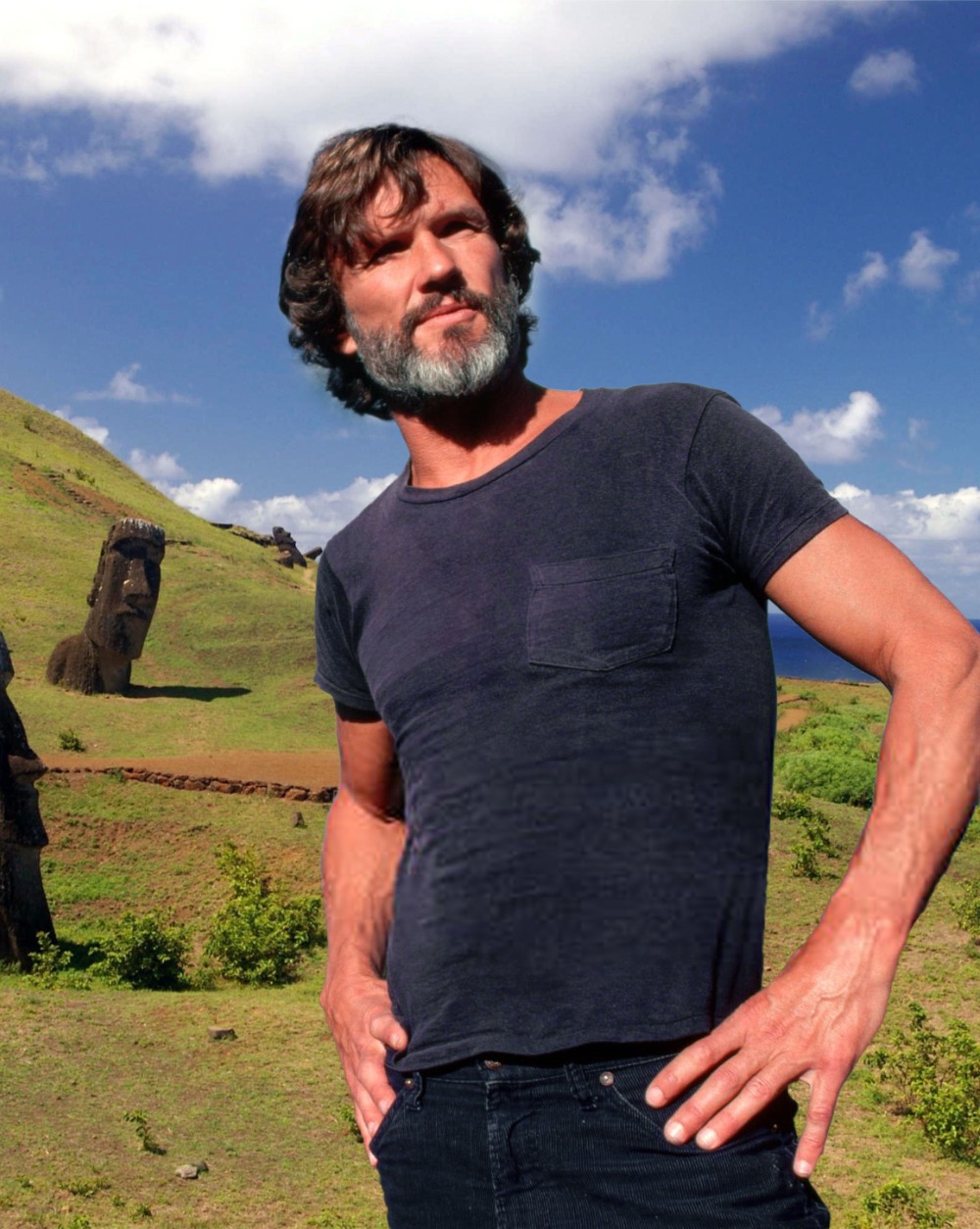

Kris Kristofferson would go on to achieve extraordinary success—not just in music, but also in film. Yet many fans still point to his early 1970s output as his most essential work.

“The Silver Tongued Devil and I” captures him at a pivotal moment: hungry, reflective, and uncompromising. It documents a songwriter turning personal insecurity into universal art.

For listeners who appreciate storytelling-driven country—especially those drawn to the golden era of the late ’60s and early ’70s—the song remains a masterclass in emotional economy. It proves that sometimes the most powerful drama unfolds not in grand gestures, but in silent hesitation.

Final Thoughts

“The Silver Tongued Devil and I” isn’t just a song about a man in a bar. It’s a meditation on temptation, identity, and the stories we tell ourselves about who we are.

Set against the backdrop of Nashville’s Music Row and born from lived experience, it stands as one of the clearest expressions of Kristofferson’s artistic philosophy: honesty above all else.

In the smoky glow of the Tally-Ho Tavern, with a drink in hand and doubt in his heart, Kris Kristofferson didn’t just write a song—he wrote a confession. And in doing so, he gave country music one of its most enduring portraits of the human condition.