There is a precise point in the life of every truly great, slightly abrasive rock-and-roll band when they must either compromise for the masses or retreat into the protective shade of the cognoscenti. For The Small Faces, that moment arrived on January 28, 1966, wrapped in a two-minute-55-second explosion of pop perfection called “Sha La La La Lee.” It was a song they didn’t write, a sound they reportedly bristled at, and yet, it was the exact piece of music that launched the scrappy East London mods out of the clubs and onto the national stage, permanently altering their career arc.

I’ve always felt a specific, almost cinematic charge when the song drops into a mix—not a club DJ set, mind you, but late at night, in the solitary glow of a high-quality home audio system. You’re alone with the sound, and the sheer, unadulterated lift of the track is undeniable. It’s a sonic snapshot of a moment in time: the tail end of the R&B fixation, the dawn of British pop’s flirtation with pure, unselfconscious euphoria.

The band was just finding its feet on the charts when this single hit. Signed to Decca Records, they had established their early sound with the fierce R&B blast of “Whatcha Gonna Do About It.” They were mod royalty in London, all sharp suits, energy, and soulful grit, but they hadn’t cracked the absolute upper echelon of the UK singles chart. Then came “Sha La La La Lee,” a track penned by the experienced songwriting duo of Kenny Lynch and Mort Shuman. It wasn’t a product of the developing, fertile partnership between singer Steve Marriott and bassist Ronnie Lane; it was an outside job, a clear bid for mainstream radio play. And it worked, vaulting them up to a Number Three peak in the UK.

This track effectively bridges the gap between the initial, raw sound on their self-titled debut album—which it later appeared on—and the more sophisticated pop psychedelia they would master later on Immediate Records. Crucially, “Sha La La La Lee” is also the first single to feature the newly recruited Ian McLagan on keyboards, replacing Jimmy Winston. McLagan’s dynamic, driving organ work is central to the track’s signature texture, a throbbing counterpoint to the insistent beat.

Anatomy of an Unwilling Hit

The core arrangement is a study in focused, high-energy simplicity. The driving force is the rhythm section: Ronnie Lane’s bass line is propulsive yet melodic, a thick, rounded anchor against Kenney Jones’s drumming. Jones is pure motorik energy here, a relentless, crisp attack on the snare and cymbals that sounds urgent and live. The texture is dominated not by the traditional rock instruments, but by the organ, the heart of the track’s mod-soul aesthetic. McLagan’s piano is present, too, often buried in the mix, lending a touch of barrelhouse bounce to the relentless groove, but it’s the Hammond organ that coats the entire piece of music in its unmistakable, swirling texture.

Then there is Steve Marriott. At this stage, he was already established as a powerhouse vocalist, a rare English singer who could genuinely channel the intensity and ache of American R&B heroes. On “Sha La La La Lee,” he delivers the call-and-response refrain with a bright, almost playful energy that contrasts sharply with the guttural sincerity of his later work. There’s a lightness, a youthful swagger in his delivery that makes the admittedly lightweight lyrics irresistible.

The song’s construction is pure, mid-sixties pop craft. A short, sharp intro leads immediately into the verse, building momentum through repetition and a deceptively complex use of dynamics. The guitar work, primarily from Marriott himself, is functional rather than flashy, a bright, slightly abrasive rhythm chop that keeps the track skipping forward. It’s not a showcase for blues histrionics, but a masterclass in economy. This is what you learn when you move beyond basic guitar lessons and study rhythm playing in the pocket: every strum serves the relentless forward motion.

It is worth noting the production, handled in part by the band themselves, alongside reported collaboration with Kenny Lynch. The recording has the characteristic bright, somewhat compressed sound of mid-sixties UK studio work—a little boxy, perhaps, but aggressive and loud, designed to jump out of a small transistor radio speaker.

“It is a track where the inherent soulfulness of the band struggles delightfully with the commercial imperative of the single market.”

The band’s famous ambivalence toward the song—they considered it too commercial and too far removed from the R&B they loved—is a crucial part of its legend. This artistic tension, however, is precisely what gives the track its unique fizz. It’s the sound of a talented, streetwise band reluctantly playing the pop game, but doing so with such undeniable energy and style that they transcend the material. They couldn’t help but make it sound great, even if it wasn’t “theirs.”

Imagine a moment, decades later, walking home after a night out. The air is cool, and you pull out your phone, queuing up a playlist. You’re looking for a jolt of simple, unironic joy. This is where “Sha La La La Lee” comes in. It doesn’t ask for contemplation; it demands movement. It is the sound of London in a very specific, optimistic, sharp-edged year, before the paisley shirts fully took over and the mood shifted to psychedelia. It’s a clean hit of pure mod exuberance, a track that cuts through the decades with its bright, unblemished energy.

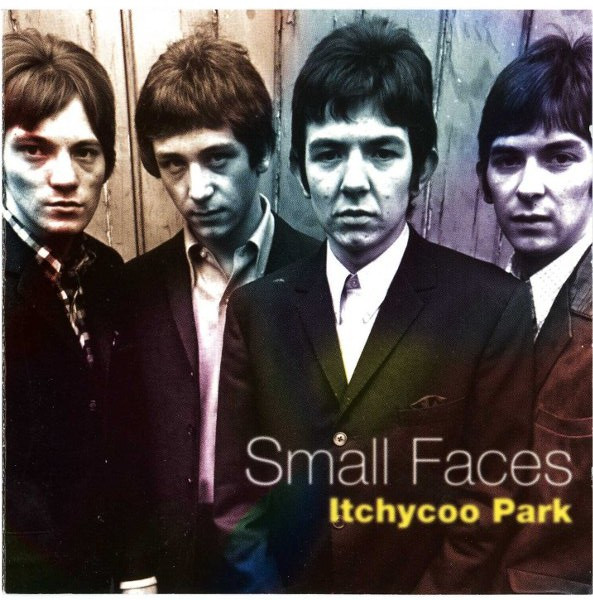

It is this forced simplicity, this reluctance to over-complicate, that makes the song timeless. It solidified the Small Faces’ place in the rock pantheon, giving them the breathing room and the chart success to later experiment with their own, more ambitious compositions like “All or Nothing” and “Itchycoo Park.” Without the unashamed pop power of “Sha La La La Lee,” their artistic freedom might have been constrained. It was the necessary compromise that bought them the space to be revolutionary. A magnificent piece of accidental brilliance.

Listening Recommendations

- The Kinks – “All Day and All of the Night” (1964): Shares the same raw, driving, and essentialist energy of early British rock packaged for pop radio.

- The Who – “The Kids Are Alright” (1966): Similar mod-era urgency and youthful anthem quality, anchored by insistent drumming and key changes.

- The Spencer Davis Group – “Gimme Some Lovin'” (1966): Features a powerhouse white-soul vocal and a dominant, driving organ line, much like “Sha La La La Lee.”

- The Move – “I Can Hear The Grass Grow” (1967): Excellent transition between mod pop/R&B punch and the coming psychedelic studio sound.

- Manfred Mann – “Sha La La” (1964): A different song, but sharing a similar, simple vocal refrain and a tight, R&B-influenced pop structure.

- The Creation – “Painter Man” (1966): A deep cut that exemplifies the high-energy, art-pop sound of the Mod scene in the year this song charted.