The world in August 1965 felt less like a steady stream and more like a series of sharp, electric jolts. The first of those jolts, the one that truly changed the frequency, arrived not with a psychedelic shimmer, but with a four-piece suit, an urgent bassline, and a teenage scream. That sound belonged to the Small Faces, and the weapon was their debut single, “What’Cha Gonna Do About It.”

It’s a piece of music so concise, so focused in its aggression, that it barely crosses the two-minute mark. To listen to it today is to be instantly transported to a sweat-slicked club in London’s East End, where the scent of Brut aftershave mixes with the cigarette smoke and the sheer volume of a young band finding their voice. This wasn’t the genteel pop of earlier British acts; this was the sound of a generation demanding attention, and it’s a sound that holds up even on the most demanding premium audio setups.

Context: The Mod Gospel According to Decca

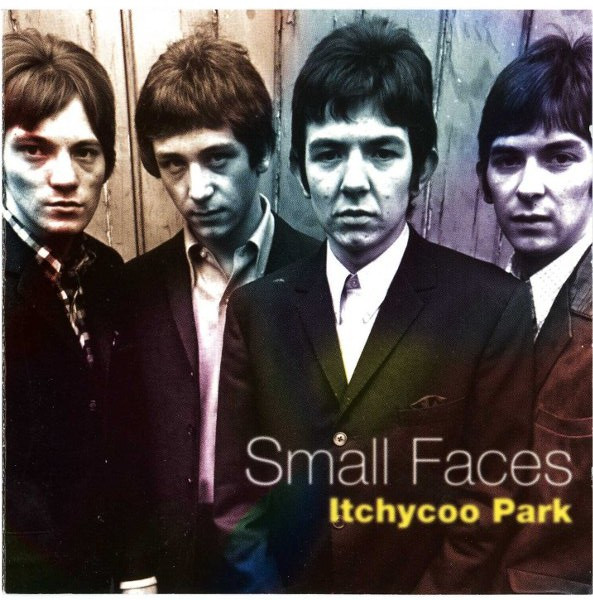

This track’s importance stretches far beyond its brevity. It was the launching pad for The Small Faces, a band whose career trajectory would become a perfect, chaotic mirror of the Mod movement itself: intense, short-lived, and brilliantly influential. Released on Decca Records, “What’Cha Gonna Do About It” announced the arrival of the quartet—Steve Marriott on lead vocals and guitar, Ronnie Lane on bass, Kenney Jones on drums, and original keyboardist Jimmy Winston—just as they were moving out of the purely cover-band circuit and into their own songwriting stride.

The song would later anchor the band’s self-titled 1966 debut album, a raw testament to their early R&B power. But initially, this was a statement on vinyl, a non-album single produced by Ian Samwell, known for his early rock and roll credentials with The Shadows. Samwell’s role was crucial, helping to translate the band’s frantic, live energy into a studio recording that retained its punch. The result hit the UK singles chart, peaking in the Top 20, a respectable launch that validated their swagger.

The core instrumental motif, a descending two-note figure, was undeniably “borrowed” from Solomon Burke’s “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love,” but the Small Faces twisted it, amplified it, and injected it with a purely British urgency. This was the genius of their early career arc: taking American soul and R&B and filtering it through a uniquely London, working-class lens of style and youthful hunger.

The Sound: A Masterclass in Compact Attack

The instrumentation is a lesson in economy. Every note serves the explosive whole. The song kicks off with an iconic blast of feedback from Marriott’s guitar, a brilliant, untamed squall that immediately tells the listener this won’t be a tidy affair. This is raw, glorious noise, a moment of intentional sonic chaos that pre-dates similar experiments in mainstream rock.

Underneath this opening salvo, Ronnie Lane’s bassline provides the track’s relentless, driving pulse. It’s not a meandering melodic part, but a locked-in, kinetic rhythm that drags the listener along. Kenney Jones, still a teenager, attacks his drum kit with a lean ferocity; the snare hits are sharp and dry, pushing the tempo ever forward without unnecessary ornamentation. There’s no fat on this arrangement—it’s pure muscle.

Jimmy Winston’s contribution on the organ, and reportedly some early piano work in the rehearsal phases, offers a thick, percussive texture. His Hammond organ part is less a soloist’s showcase and more a rhythmic component, bubbling beneath the surface, reinforcing the R&B foundation while adding a necessary gritty depth to the overall sonic canvas. The absence of string sections or orchestral sweep is definitive; the power comes from four instruments played with maximum attack.

Marriott’s vocal performance is the true star. His voice, already a powerhouse despite his age, cracks and strains with a conviction that few British singers of the era could match. He doesn’t just sing the lyrics; he yells them, pushing the microphone to the edge of distortion, his phrasing a breathless, impassioned plea. “I want you to know that I love you, baby,” becomes a declaration of war, a teenage existential crisis compressed into a high-octane shout.

“This is the sound of ambition running on pure adrenaline and youthful, untamed talent.”

The production is suitably unfussy, favoring clarity of impact over studio sheen. The drum sound is tight, the bass is forward, and the feedback, initially an accident according to lore, is kept in, a testament to the band’s embrace of sonic grit. It is a thrilling exercise in dynamics: the verses maintain a tight coil of tension, and the brief chorus explodes into a call-and-response that begs for a dancefloor riot.

A Modern Resonance

While the track is steeped in the specific cultural moment of Mod London, its energy transcends time. Today, when I pull up this track on my system, I’m struck by how current its economy feels. The two-minute sprint prefigures the punk ethos that would arrive a decade later, yet it does so with a soulful foundation that punk often discarded.

It offers a micro-story in itself: think of the modern listener, scrolling through playlists on a music streaming subscription, when this track suddenly cuts through the algorithmic noise. It’s impossible to ignore. It’s a wake-up call, a reminder that brilliance does not require four movements or an eighteen-piece orchestra. It just requires the right riff and the willingness to push the faders past the red.

This tight, explosive arrangement is a challenge to any budding musician. Forget the complex structures of progressive rock; study “What’Cha Gonna Do About It” for its perfect distillation of intent. Any beginner taking guitar lessons would benefit from understanding how Marriott utilized simple power chords and that startling feedback to create a compelling, immediate hook. It’s a foundational piece of R&B-infused garage rock that remains structurally perfect.

The track’s enduring appeal lies in its authenticity—the feeling that this is a song played by four short kids who genuinely believed they were the toughest, sharpest band in town, and played like their rent was due in 120 seconds. They captured the nervous, exhilarating tension of youth, the quick shifts from tenderness to anger, all within that compressed timeframe.

Listening Recommendations: Adjacent Rushes of Energy

- The Who – “My Generation” (1965): Another definitive Mod anthem; shares the same anti-establishment fire and bass-driven urgency.

- The Kinks – “You Really Got Me” (1964): Features a similar raw, distorted guitar riff that acts as the primary engine for the track.

- The Action – “Land of a Thousand Dances” (1966): Excellent example of British Mod soul, showcasing vocal power and tight R&B musicianship.

- The Spencer Davis Group – “Keep On Running” (1965): Gritty, high-energy British R&B with a soulful vocal powerhouse (Steve Winwood) at the helm.

- The Yardbirds – “For Your Love” (1965): Though more psychedelic, it captures the raw intensity and innovative instrumental use of the early British R&B scene.

- The Animals – “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” (1965): Features the same urgent, life-or-death vocal delivery and working-class lyrical theme.

This recording remains a vital flashpoint in the history of British rock and soul, a perfect opening statement that never lost its power. Put it on, turn it up, and let the sheer audacity of those two minutes remind you what passion sounds like.