I remember the exact moment the grit of the 1960s crystallized for me. It wasn’t a pristine Beatles track or a psychedelic flourish from the Summer of Love. It was a cold, late-night drive, the AM radio fading in and out of static as I cruised an anonymous stretch of highway. A primal, two-note riff cut through the hiss, a sound drenched in reverb and something harder to place—a tangible sense of sneering, swaggering youth. The disc jockey, his voice a weary balm, eventually mumbled the title: “Dirty Water,” by The Standells.

This piece of music was an instant education. It wasn’t the polished Los Angeles sound of sun and surf. This was the sound of a band that had been kicking around for years, finally capturing the volatile, unpretentious energy of the garage rock movement. This single, first released in late 1965 and the centerpiece of their most successful album, 1966’s Dirty Water, was not initially destined for greatness. It was a slow burn, recorded in Hollywood but gaining traction far from the glitz of their home base.

The Grime and The Glory: Producer Ed Cobb’s Blueprint

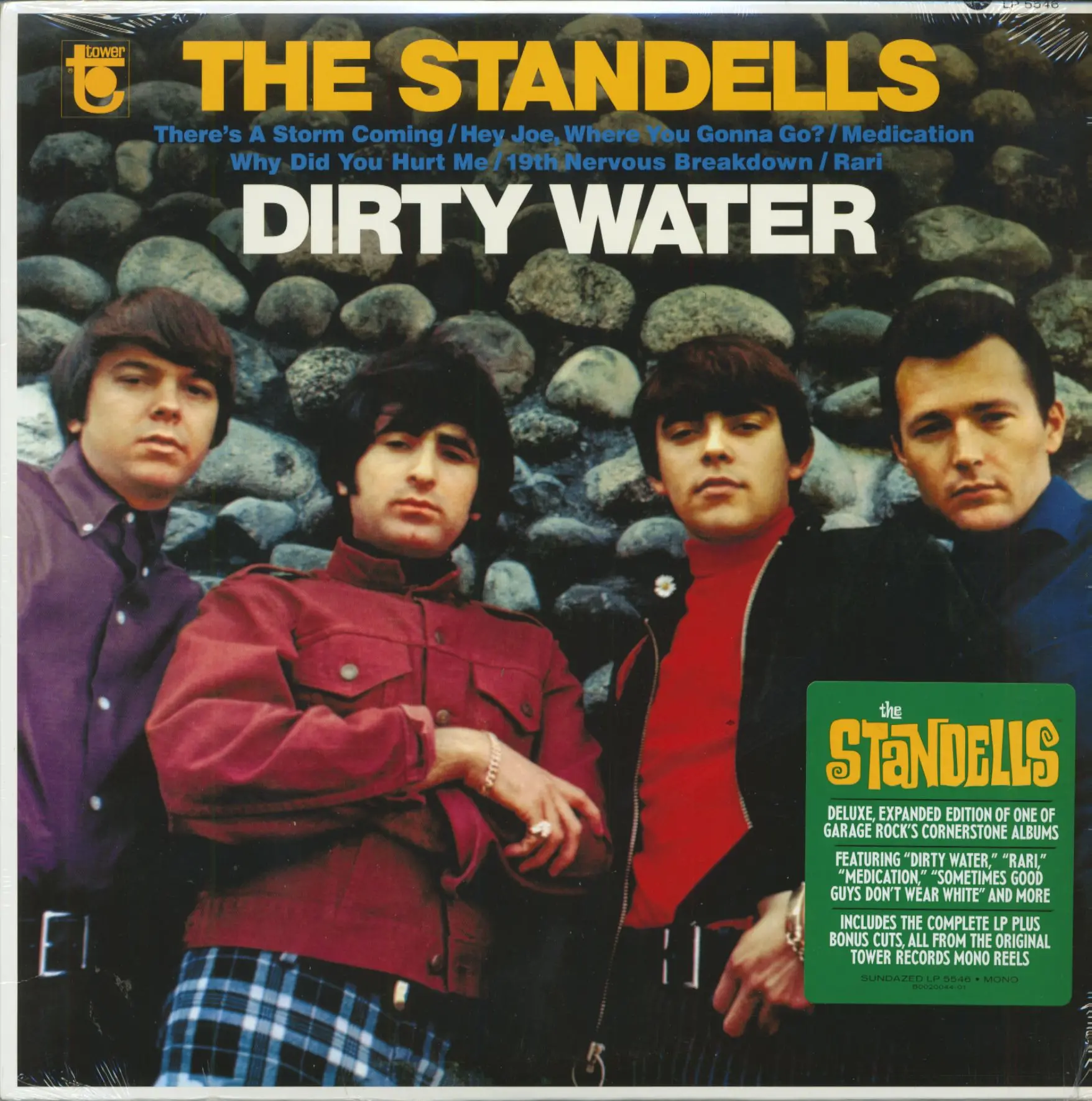

The architect of this sonic manifesto was producer and songwriter Ed Cobb—best known perhaps for writing “Tainted Love,” an irony not lost on connoisseurs of gritty music. Cobb took a Los Angeles band—Dick Dodd on drums and lead vocals, Tony Valentino on guitar and harmonica, Larry Tamblyn on Vox Continental organ and backing vocals, and Gary Lane on bass—and, reportedly, channeled a mugging he experienced in Boston into a mocking paean to that city’s famously polluted Charles River and harbor. What The Standells delivered, however, transcended the localized joke. They delivered proto-punk.

The single, released on Tower Records, a subsidiary of Capitol, was the pivot point in The Standells’ career arc. Prior efforts had been scattered, including a live album and a string of minor singles. “Dirty Water” became their breakout hit, a national success that climbed to the top 15 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the summer of 1966. It was a smash born of two raw ingredients: a simple, unforgettable riff and an overwhelming sense of attitude.

The arrangement is a masterclass in economy. The instrumentation is classic mid-sixties garage: drums, bass, electric guitar, and the indispensable Vox Continental organ. The immediate attack comes from the guitar riff—a three-chord wonder played by Tony Valentino, simple yet possessing a sustain that is utterly corrosive. It’s less a melody and more a jagged textural hook, establishing the mood of urban decay and cool indifference within the first few seconds.

The rhythm section is mercilessly direct. Dick Dodd’s drumming is simple but propulsive, his drums sounding tightly tuned, almost brittle, but driving the track with unwavering commitment. Gary Lane’s bassline provides the necessary subterranean anchor, locking in with the drums to create a foundation that is heavy and relentless.

The Gritty Heart of the Machine

Where the song truly transcends the simple rock format is in its textures. Larry Tamblyn’s Vox Continental organ is the secret weapon, its thin, buzzing timbre weaving through the track like a siren in the smog. It’s not the bright, carnival-esque sound that some pop groups employed; here, the Vox is a grimy, menacing texture, providing a counter-melodic hum that is both eerie and danceable. In the absence of a piano, this organ fills the melodic space, giving the track its distinctive, slightly unsettling atmosphere.

The lead vocal, delivered by drummer Dick Dodd, is a perfectly pitched sneer. It’s half-sung, half-spoken, dripping with a fatigued but defiant swagger that delivers the lyrics’ tales of “lovers, muggers, and thieves.” The microphone placement seems close, capturing the immediacy of the performance, lending a feeling of being right there in the small, hot room where the tape was rolling. There’s a glorious, almost amateurish quality to the sound—a directness of signal that separates it from the more heavily engineered pop of the era. The Standells’ sound here, raw and undiluted, would later inspire countless groups in the burgeoning punk and new wave scenes.

“This is the sound of the un-scrubbed 1960s, a three-chord riot packaged for a world that thought pop music should always sparkle.”

The recording quality, particularly the reverb tail on the vocals and the fuzz-drenched guitar tone, gives the track a sense of necessary space. This isn’t a technically pristine recording; it’s a documentation of energy. This sound aesthetic is what drew me in that night on the highway—it felt honest, a reaction against the orchestral sweep of more sophisticated records. While many today seek out high-resolution formats and the clearest possible signal to enhance their premium audio experience, sometimes the magic is found in the distortion and the decay, the way the cheap mic and the overworked amp conspire to create a sound bigger than the parts. It’s a crucial lesson often overlooked by those obsessed with flawless fidelity.

Beyond the Charles River

The ultimate power of “Dirty Water” lies in its ability to take a specific, almost geographically petty gripe—a complaint about a river in Boston—and transform it into a universal rallying cry for those who love the beautiful mess of a city. The line, “Boston, you’re my home,” delivered with that deadpan, resigned finality, is pure defiance. It says: My home is flawed, it’s dangerous, it’s polluted, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. It’s the sonic equivalent of a worn leather jacket—a little beat up, a little dirty, but absolutely essential.

Think of the enduring appeal. It’s why, decades after its release, it became an anthem for the Boston Red Sox, a celebration of underdog grit. It took the song from a minor rock classic in the historical context of a compilation album like Nuggets to a perpetual cultural artifact. For a band that began in the earlier decade of rock and roll, this piece of music cemented their legacy as forefathers of a rougher, more stripped-down sound. It proves that the foundation of rock—the relationship between the electric guitar, the drums, and a simple song structure—remains eternally powerful.

I recently watched a young guitarist struggling through their initial guitar lessons, focusing on scales and complex fingerings. I wanted to tell them: Forget the pyrotechnics for a moment. Go listen to “Dirty Water.” Understand the primal force of a two-note riff repeated with absolute conviction. The song’s legacy isn’t in its complexity; it’s in its directness.

The Standells only briefly enjoyed their moment in the national spotlight before the tides of psychedelia and pop-rock refinement pulled them back. Yet, their contribution is undeniable. They gave the mid-sixties garage scene a permanent place on the pop charts, offering a blueprint for grit that still feels urgent and fresh today. It’s a testament to producer Cobb’s vision and the band’s raw execution that this single endures, a gloriously trashy hymn to urban decay and stubborn pride. Don’t stream it in the background; crank it up and let the dirty water wash over you.

Listening Recommendations: For Fans of Gritty Garage and Proto-Punk

- The Seeds – “Pushin’ Too Hard” (1966): Shares the same sneering vocal delivery and the essential use of the Vox organ as a lead instrument.

- The Shadows of Knight – “Gloria” (1966): Features a similarly raw, blues-punk guitar attack and a focus on elemental, three-chord simplicity.

- The Count Five – “Psychotic Reaction” (1966): Built around a visceral, two-note riff and a dramatic mid-song breakdown, embodying the era’s intensity.

- The Troggs – “Wild Thing” (1966): A primal, unforgettable rock classic relying on only three chords and a raw, almost childlike vocal power.

- The Knickerbockers – “Lies” (1965): Blends the British Invasion sensibility with American garage grit, featuring crisp harmonies over a tight, driven rhythm.

- The Remains – “Don’t Look Back” (1966): A lesser-known gem from the same era that captures a similar desperate, high-energy rock and roll urgency.