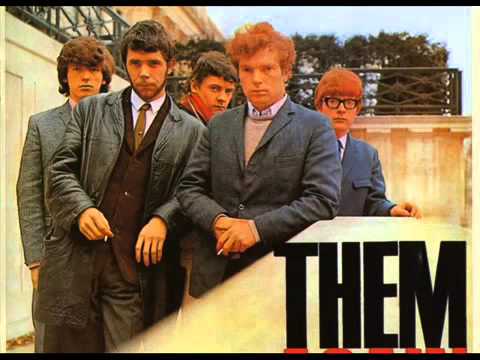

The air in the club was thick, smelling of stale beer and desperation. A single, naked bulb swung above the stage, illuminating the kind of sweat-and-leather intensity that rarely translates to vinyl. This wasn’t a stadium; it was the Maritime Hotel in Belfast, 1964, a place where a barely-formed band called Them, fronted by a fierce, almost sullen young man named Van Morrison, hammered out a sound that felt dangerous and utterly new. This visceral energy is the ghost trapped inside the grooves of “Gloria,” a piece of music that began as a live exorcism before it was reluctantly committed to tape.

It’s easy, decades later, to forget that this towering monolith of rock history was, at the time, merely a B-side. Released in the UK on Decca Records in November 1964, “Gloria” played second fiddle to the cover of Big Joe Williams’ blues standard “Baby, Please Don’t Go.” This placement is telling. The A-side was the nod to tradition, the expected R&B homage from a British Invasion band; the B-side was the Trojan horse, a blast of raw, original teenage desire disguised in a three-chord riff. It would later be added to Them’s debut UK album, The Angry Young Them, released the following year, cementing its place in the fledgling canon of rock’s first wave.

The Grinding Gears of Proto-Punk

The beauty of Them’s “Gloria” lies in its almost aggressively simple architecture. It’s an aural monument to economy, a testament to how much can be achieved with so little. The instrumentation is classic 1960s R&B grit, but stripped of any pretense. The track was reportedly overseen by legendary Decca producer Dick Rowe, a figure often associated with early British rock. Yet, the recording doesn’t sound polished or meticulously arranged; it sounds captured, like a wild animal cornered in the studio.

The core of the sound is the rhythm section, which operates with a relentless, driving simplicity. The bass is thick and foundational, laying down a hypnotic, repeating pulse that never wavers. It’s a sonic anchor for the escalating tension. Crucially, the guitar work is pure, unvarnished rhythm and power. There are no soaring leads, no virtuoso breaks—just a sharp, overdriven strumming pattern that hammers the I-IV-V progression into the listener’s skull. The texture is rough, the timbre biting, suggesting a low-fidelity microphone pushed to its limit to capture the sheer volume. It’s the sound of a garage band, even if it was recorded in a proper studio. If you listen closely on a set of good premium audio speakers, you can practically hear the room vibrating around the drum kit.

Van Morrison’s vocal performance, however, is the track’s true dynamo. He doesn’t sing the lyrics so much as he declaims them, a mix of R&B bark and spoken-word menace. That famous, drawling, semi-chanted introduction—”I said G-L-O-R-I-A”—is a masterclass in slow-burn anticipation. It’s not just spelling out a name; it’s building a cult around it, granting the mundane name a mythic weight. The entire track builds dynamically, a slow, greasy slide towards a catharsis that is never fully reached—it just cuts off, leaving the listener hanging.

The Allure of the Forbidden Chord

For aspiring musicians of the era, “Gloria” wasn’t just a song; it was a syllabus. The fact that any kid with a cheap electric guitar and a slightly broken amp could master the chords—E, D, and A—meant that this raw, powerful sound was instantly democratized. It was a rallying cry against the orchestral sweep of some contemporaneous pop; this was music you didn’t need a professional arranger or piano for, only attitude.

This accessibility is precisely what propelled it from a minor regional curiosity—it notably found great success in the Los Angeles area long before the rest of the US national charts picked it up, peaking on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1966 after a hugely popular cover by The Shadows of Knight—to a foundational text. It provided the template for countless teen bands, offering a way to sound dangerous and cool without needing advanced guitar lessons or a deep understanding of complex jazz changes. It was rock and roll distilled to its essential, volatile elements.

“The original 1964 recording of ‘Gloria’ is not just a song; it is a declaration of independence, signed with three chords and a snarl.”

The genius of the song is its narrative brevity. The entire lyric is essentially a six-line stanza repeated and rearranged, focusing on a midnight visit from a girl whose name is spelled out as a devotional mantra. It’s primal, repetitive, and deeply sexual in its implied narrative—a simplicity that forced other bands, notably The Doors and Patti Smith, to reimagine and expand upon its form years later. Morrison gave them the framework of a legend, and they built their own stories inside it.

This piece of music endures because it speaks to the elemental desire for transgression. The whole world of 1960s British R&B was about taking the raw blues of America and making it white-knuckle, urgent, and loud. Them’s “Gloria” is the purest example of this transfer. It carries the weight of a back-room gig, the intensity of a crowd pressed right up against the stage, and the electrifying promise of a late-night rendezvous. It is an artifact of the moment when rock learned to stop asking permission and start demanding attention.

It’s worth reflecting on how a simple, less-than-three-minute blast of sonic testosterone came to define not just a band, but a genre. Them, as a band, was notoriously unstable, essentially a vehicle for the tempestuous genius of Van Morrison. But in this track, for a breathless 2 minutes and 38 seconds, they were a perfectly fused machine. The subsequent history of rock is littered with its echoes, from the minimal ferocity of the Velvet Underground to the punk ethos of the Ramones. It is a song that remains vital not in spite of its simplicity, but because of it. Pull out the speakers, crank the volume, and feel the history.

Listening Recommendations

- The Shadows of Knight – “Gloria” (1966): A slightly cleaner, Americanized cover that was a major US hit and helped introduce the song to a wider audience.

- The Doors – “Gloria” (Live, 1983 release): Jim Morrison’s famous, lengthy ad-libbed take demonstrates the song’s adaptability as a live, psychedelic jam vehicle.

- Patti Smith – “Gloria” (1975): An utterly transformative version that uses the core riff as a launchpad for her iconic feminist-punk poem, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine.”

- The Animals – “Boom Boom” (1964): Shares the same raw, R&B-influenced garage band dynamic and prominent, simple guitar riffing.

- The Troggs – “Wild Thing” (1966): Another masterpiece of rock minimalism, built on a few simple chords and a raw, lustful vocal delivery, much like “Gloria.”

- The Kinks – “You Really Got Me” (1964): An almost contemporary track that similarly defined the raw, loud, and guitar-driven sound that garage and hard rock would embrace.