Imagine the air in a London studio, mid-1964. It’s thick with the smell of hot vacuum tubes and cigarette smoke. The space is small, the soundproofing is functional at best, and a group of young, hungry musicians from Belfast are about to tear a hole in the fabric of popular music. The red light flicks on. There’s no click track, just a shared, primal count-off. Then, it happens: a jagged, menacing slash of sound.

It’s a guitar riff that doesn’t invite you in; it corners you. It’s not clean, it’s not polite. It’s a saw-toothed warning, a declaration of intent that rips through the speaker and announces that the next two minutes and forty-two seconds will be anything but comfortable. This is the opening salvo of Them’s version of “Baby Please Don’t Go,” and it is the sound of rock and roll getting its hands dirty.

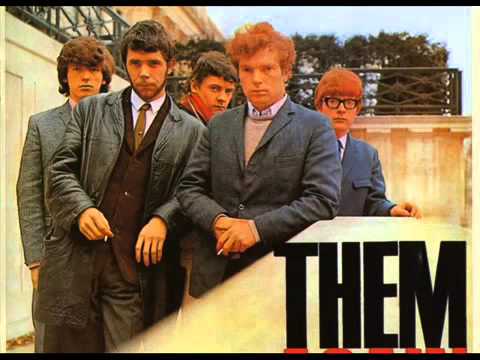

Originally a 1935 blues lament by Big Joe Williams, the song had been a standard for decades. But in the hands of Them, it was no longer a plea. It was a threat. This was the group’s second single for Decca Records, a crucial moment in the frantic arms race of the British R&B boom. Bands like The Rolling Stones and The Animals were already translating American blues for a UK audience, but Them’s approach felt different. It was less reverent, more volatile.

The session was helmed by the brilliant American songwriter and producer Bert Berns, a man who understood the alchemy of grit and melody. He had a knack for finding the raw nerve in a performance and putting a microphone right on it. With Them, and specifically with their frontman, a ferocious teenager named Van Morrison, he found an entire network of exposed wiring.

The riff, now the stuff of legend, was reportedly laid down not by the band’s regular guitarist but by a young, in-demand session player named Jimmy Page. While accounts vary, the sound itself is undeniable proof of a paradigm shift. It’s a clipped, aggressive, and slightly distorted lick that functions as the song’s central nervous system. It repeats with a hypnotic insistence, a rhythmic anchor in the ensuing chaos. This is not the fluid, lyrical playing of the blues masters; this is the sound of the city, of concrete and anxiety, channeled through six steel strings. The simple, muscular pattern proved you didn’t need complicated guitar lessons to change the world; you just needed an unforgettable idea and the conviction to play it like you meant it.

Then comes the voice. Van Morrison, not yet twenty years old, sounds less like he’s singing a lyric and more like he’s expelling a demon. His phrasing is a marvel of tension and release. He doesn’t just sing the title; he gargles it, spits it, begs it. “Baby, please don’t go!” is a ragged, desperate cry from the back of the throat. He stretches the word “down” into a multi-syllabic groan—“Well I’m goin’ down to New Orleans…”—as if the very act of enunciation is a physical burden.

This isn’t the calculated cool of many of his peers. It’s an authentic, almost frightening display of raw emotion. You believe him. You believe that if the person he’s singing to walks out that door, his world will collapse into dust. It’s the sound of a man who has glimpsed the abyss and is screaming to keep from falling in. He pushes his voice to the breaking point, a feral bark that cuts through the dense mix.

The rest of the band creates a perfectly frantic bed for Morrison’s vocal exorcism. The rhythm section is a runaway train, a relentless shuffle that pushes the tempo, creating a sense of urgency and forward momentum. The bass is a low throb, more felt than heard, while the drums are a splashy, energetic crash. There’s a subtle, almost-buried barrelhouse piano that adds a layer of authentic blues tonality, grounding the track in its roots even as the performance tears those roots from the soil.

Listening on a pair of good studio headphones reveals the delicious chaos in the margins—the slight bleed between instruments, the audible intake of breath before a vocal line, the raw energy of a band playing live in a room together. Berns’s production is a masterclass in controlled mayhem. He compresses the sound until it feels like it’s about to burst, forcing every element to fight for space. The result is a dense, claustrophobic piece of music that feels immediate and confrontational.

“It isn’t a recording of a song; it’s the sound of a controlled detonation, captured just before the shrapnel hits.”

Picture a teenager in 1965, huddled over a transistor radio late at night, twisting the dial past the polished pop of the era. Suddenly, this raw, elemental noise erupts from the tiny speaker. It would have been a revelation, a jolt of pure adrenaline. It was music that acknowledged the darkness, the frustration, and the wild energy simmering beneath the surface of post-war society. It was dangerous.

The song was released as a single and also served as a cornerstone of their debut album, 1965’s The Angry Young Them. The title was fitting. The entire collection seethed with a similar kind of defiant energy, but “Baby Please Don’t Go” was its most potent and distilled expression. It became their first major hit in the UK and put them on the map, defining their sound and establishing Morrison as one of the most compelling and unique voices of his generation.

Decades later, the track has lost none of its visceral power. In an age of digital perfection and auto-tuned vocals, its raw humanity is more striking than ever. It’s a reminder of a time when rock and roll was a visceral, physical force—a sound you could feel in your bones. It’s the sound of a band, and a singer, with nothing to lose, pouring every last ounce of their being into a two-and-a-half-minute masterpiece of desperation and desire.

To listen to this piece of music today is to plug directly into the raw, untamed spirit of the 1960s. It’s a testament to the enduring power of a simple riff, a desperate voice, and the electrifying moment when they collide. Turn it up. Let the chaos in.

Listening Recommendations

- The Animals – “The House of the Rising Sun” (1964): For another definitive, dark, and trans-Atlantic reinvention of a folk-blues standard by a British R&B group.

- The Yardbirds – “For Your Love” (1965): Captures a similar sense of brooding, minor-key intensity and marked a creative turning point for a legendary band.

- The Spencer Davis Group – “Gimme Some Lovin'” (1966): Shares that same explosive, organ-driven R&B energy and a powerhouse vocal from a prodigiously talented teenager, Steve Winwood.

- The Rolling Stones – “19th Nervous Breakdown” (1966): Showcases a similarly jagged, relentless guitar riff and a frantic, high-anxiety performance that defines the era.

- Bo Diddley – “Who Do You Love?” (1956): A foundational American track built on a hypnotic, threatening groove that directly inspired the British R&B movement.

- The Sonics – “Have Love, Will Travel” (1965): An American garage-rock parallel, offering a similarly raw, overdriven, and gloriously unhinged take on R&B.