There’s a special kind of tenderness in Conway Twitty’s “I Love You More Today.” From the very first note, his voice carries the weight of devotion—steady, unwavering, and deeper with every passing day. 🌹 It’s a song that reminds listeners of love that grows stronger through time, even when tested by distance or doubt. For fans who remember Conway spinning on their turntables, this ballad isn’t just music—it’s a vow set to melody, a promise echoing through the years, touching hearts just as powerfully now as it did then. 💫

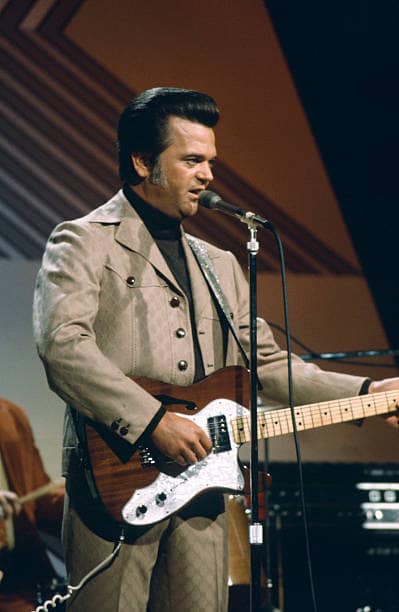

It begins like a door opening softly, not for spectacle but for a conversation. The band breathes in, the tempo settles, and Conway Twitty steps to the center of the frame with that warm baritone—confiding, unhurried, certain. On first pass, “I Love You More Today” plays like something you’ve known forever, a country promise spoken plainly. But sit with it—really sit—and you hear the discipline underneath the ease: the way phrases land on the beat and then lean off it; the controlled air in the vibrato; the exactness of each consonant. It’s the difference between sentiment and craft.

In 1969, “I Love You More Today” arrived as Twitty’s career was solidifying its second act. The former rock ’n’ roll hitmaker of the late ’50s had already crossed into country several years earlier; by the time this single appeared on Decca, he was no tourist. He was building a home. The song, written by L. E. White, became the title track of a release that marked his climb toward the long run of chart toppers that would define the 1970s. Owen Bradley—one of Nashville’s most consequential producers—guided the session, and you can hear his fingerprint in the smoothness: rounded edges, careful balances, and the invitation for a vocal to carry the truth without needing to shout.

The text of “I Love You More Today” is deceptively simple: love, measured not in fireworks but in increments—today more than yesterday. White’s lyric avoids grand metaphor. It sets up a modest emotional architecture in which small declarations matter because they’re repeatable. That’s Bradley’s production ethic, too. The arrangement favors presence over drama; the rhythm section moves with a gentle confidence, and the top end never grows glassy. You don’t feel compression or heavy limiting; you feel air.

Twitty’s vocal is the axis. Listen to how he lands on the word “more”—a soft press, a release, and a residual ring in the room. He rarely over-sustains; he prefers to finish the line and hand it back to the band. It’s courtship language delivered with adult calm. He’s not auditioning for love. He’s keeping it.

Instrumentally, the record is a study in late-’60s Nashville cohesion. A steady backbeat, bass that walks just enough to keep the floor moving, and what sounds like a polite, silvery steel tracing the emotional contour without showboating. A clean electric guitar tucks in small fills between the phrases, and when a softly voiced piano steps forward, it plays the benevolent neighbor—there when needed, never a chatterbox. You can practically sense the placement of mics: not bone-dry isolation, not cavernous reverb—just the kind of short, tasteful reflections that keep a voice near and a band intact. These are working musicians balancing restraint and color, which is why the record still breathes on small speakers and opens up on better rigs.

That sound doesn’t come from accident. Bradley’s reputation for countrypolitan polish preceded him, but what’s striking here is the reserve. He avoids the orchestral swell that could have tipped the track toward pop. Instead, the blend favors lightness: backing voices (if present) whisper rather than proclaim; steel decorates rather than dictates. It’s the sort of discipline you notice most when it’s absent on other records—when strings crowd the middle, or when the time feels glued to a click. Here, the pocket is human.

The song’s place in Twitty’s arc matters. It followed his initial reintroduction to country radio and arrived just before the string of hits that would culminate in songs like “Hello Darlin’.” “I Love You More Today” became one of his early country number ones, confirming that the move wasn’t an experiment; it was an address change. He anchored it with a writer he trusted (White) and with Bradley’s sonic compass, both of which helped him stabilize his identity for the decade to come.

As a piece of music, it’s an ode to proportion. There’s no long instrumental break to rewrite history. Middle eights, when they appear in this era, often act as shade rather than spotlight, and this track behaves the same. If you want fireworks, you can find them in Twitty’s later catalog. If you want proof that everyday devotion can be sung without collapsing into cliché, you come here.

I keep thinking about the way Twitty approaches the emotional math. Today is greater than yesterday, but he doesn’t promise an infinite ascent; he suggests a steady accrual. That’s more interesting than the breathless assurance of “forever.” It acknowledges doubt without dramatizing it. In a market that often prizes novelty—new hooks, louder choruses—this song cares about something else: credibility. The voice sounds like it’s been through disappointment and found a vocabulary that still honors hope.

Three small listening moments crystallize the record for me.

First, the entrance. There’s no long pickup. The band is there, and then he is, as if the room was already in motion and he stepped inside it. It feels like walking into a kitchen conversation where the coffee is already poured. You trust a singer who doesn’t need to clear his throat.

Second, the middle phrases of the first verse. He holds just enough tone at the end of a sentence to let the steel answer him—call and response reduced to a glance. The hinge is restraint: neither instrument nor voice claims dominion; each line feels shared.

Third, the final refrain. He doesn’t extend the last note with a big, cinematic hold. He eases off, allowing the band to write the period. That choice leaves the listener with the aftertaste of a promise kept, not a performance completed.

“Love songs often promise the moon; this one offers a porch light—and that’s why it feels true.”

It’s also worth hearing the record in the context of what country was doing in ’69. The genre was managing a careful negotiation between tradition and crossover. Some tracks chased pop adjacency; some doubled down on honky-tonk grit. Twitty and Bradley chose the middle lane: modern enough to sit on daytime radio, country enough to belong to the format. If you listen beside contemporaneous singles by Glen Campbell or Tammy Wynette, you hear cousins: the consonants are softened, the sibilance is tamed, the band is mixed to serve the story.

People sometimes reduce Twitty to the iconic baritone—an instrument of seduction and sympathy—but what sustains these 2½ minutes is diction. He knows how to sing around a vowel, how to color a word without repainting the sentence. That skill turns a straightforward lyric into something durable. Try covering the track and you’ll discover how hard it is to replicate “simple” when simple is the design.

The physicality of the sound matters, too. On basic earbuds, the low end stays tidy, the vocal remains forward. On better speakers—or with a good pair of studio headphones—the bass roundness and gentle high-end sheen reveal themselves, and you can locate the steel in the stereo field more clearly. This is not a gear-demo record, but it rewards attention in a way that aligns with thoughtful playback. One line of advice: if you’re upgrading your living room setup, you’ll notice how this kind of production blossoms with premium audio, letting the small inflections ride above the band rather than sinking into it.

I’m also drawn to how the record models adultness. Country has always been a home for everyday stories—bills and babies, days and years—but adultness in sound is another thing. It’s the art of letting separation and warmth coexist. You can hear each instrument where it lives, but nothing feels isolated. That’s grown-up engineering, and it matters because it underwrites the lyric’s promise: consistency.

Consider the song as part of a listener’s life now. A couple in their thirties, working opposite shifts, discovers the habit of short voice notes. They send one in the late afternoon—“Just thinking about you. More than yesterday, somehow.” The refrain is a shorthand for workaday tenderness. Another vignette: a daughter digitizes her parents’ cassettes and stumbles on this track; she doesn’t know the artist but understands the pitch of the promise. And another: an older man replaces a warped LP with a clean digital copy, not to chase nostalgia but to keep the ritual—dinner, a glass of something, and three minutes of a vow renewed.

It’s tempting to call “I Love You More Today” modest, but modesty implies lesser ambition. The ambition here is different: to articulate commitment without inflation. That’s why it’s aged well. The glossy facades of some contemporaneous productions have faded; this one retains its grain. I suspect it’s because Bradley trusted the singer, and the singer trusted the song.

In the broader context of Twitty’s discography, the track signals a clarifying moment. After earlier country successes, this single’s reception confirmed that the bet on Nashville was paying off. It also positioned him for the work that would follow—songs that took bigger swings, duets that expanded his persona, and an eventual run of industry recognition. But even if you strip away the arc and hear this record in isolation, it communicates a complete world: one voice, a band of professionals, and a promise that refuses melodrama. That’s country at its best.

We’re used to hearing time measured as loss in music—what fades, what leaves, what can’t be recovered. Twitty flips the script: time as accumulation. That vision is both romantic and practical. It says: I’ll be here tomorrow, and it’ll count. Listen again and you’ll notice how the song resists extremes. No key change, no last-minute fireworks. Just balance. In 1969, that was a statement; today, it feels like a gift.

If you’re exploring Conway Twitty for the first time, this track is a wise starting point. It gives you the vocabulary—the warmth, the calm, the conversational poise—without giving away the store. From here, follow him forward to the bigger anthems or backward to the early country years. Either way, you’ll hear how this single sits like a cornerstone.

For the record keepers: the song was released in 1969 on Decca, produced by Owen Bradley, and written by L. E. White; it served as the title track to a release of the same name and became one of Twitty’s early country number ones, helping to define his country phase moving into the next decade. Those facts matter because they anchor the listening experience inside an actual moment—one where an artist who had already lived one life on the charts was building another with patience and a superb team.

Before we close, a quick note for players and learners who come to music through the hands: the gentle pocket here teaches feel better than a metronome alone. The space between vocal line and fill, the way a tasteful lick never arrives on top of the lyric, the shape of an ending that trusts silence—these are lessons you can’t fake. If you’re mapping your own practice routine, study how the accompaniment answers the voice without ever competing. It’s a masterclass in courtesy.

There’s always a risk in praising subtle records: the praise becomes louder than the art. This one can hold it. Put the track on when the house is quiet and let the opening seconds tell you what kind of evening it wants. You’ll hear a singer content to be plausible rather than grand, and a band content to be true rather than busy. That, today—more than yesterday—feels like wisdom.

And if you’re counting, I am too. Each listen adds something. The song keeps its word.