The first time I heard the full, album-version opening—not the compressed radio edit—it was late. The kind of late where the neon outside your window casts long, blue shadows and the only company you keep is the warm glow of the stereo tubes. I was streaming a deep-cut classic rock playlist, trying to understand what constituted perfection in the American rock single of the early 1970s. Then, a sound emerged that was both completely familiar and shockingly detailed: a sparse, echoing drum fill, followed by a raw, un-processed acoustic guitar riff that cuts the silence. It wasn’t slick; it was immediate, like a tape machine had just been punched in, catching the musicians mid-breath.

That primal, almost country-rock introduction, a simple piece of music in a major key, is the deceptive genesis of Three Dog Night’s defining statement, “Joy to the World.” It’s an auditory sleight-of-hand. The track, after all, starts with a nonsense line—“Jeremiah was a bullfrog, was a good friend of mine”—and then launches into a sonic tidal wave that, in 1971, absolutely dominated the airwaves, becoming the year’s top pop single on the Billboard Hot 100.

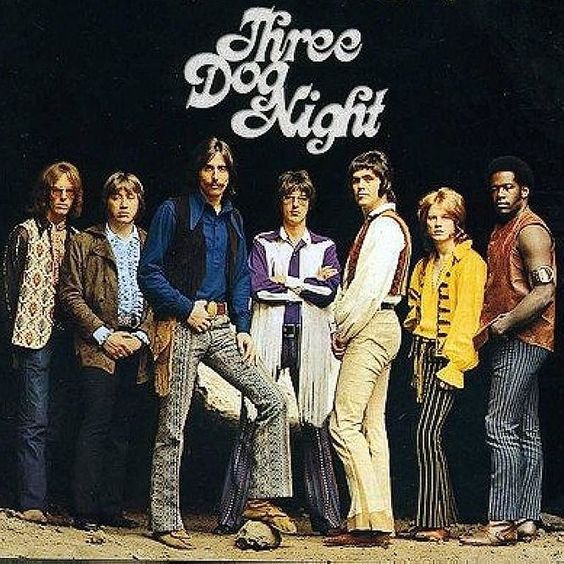

But how does a song, allegedly written by Hoyt Axton as a throwaway exercise—reportedly, a placeholder lyric for a TV cartoon that never aired—become such an enormous cultural bedrock? The answer lies in the masterful collision of material and execution, the unique engine that was Three Dog Night’s seven-man line-up, and the expert guidance of producer Richard Podolor.

The Anatomy of the Inevitable Hook

“Joy to the World” was originally tracked for the band’s fourth studio album, Naturally, released in November 1970 on Dunhill Records. At this point in their career, Three Dog Night had established a winning formula: they took exceptional, often overlooked material from contemporary songwriters (like Nilsson, Randy Newman, and Laura Nyro) and transformed it using their secret weapon—the three distinctive lead voices of Chuck Negron, Danny Hutton, and Cory Wells. This allowed them to pivot stylistically, avoiding the creative exhaustion that could hobble a single-songwriter band.

When Negron championed Axton’s whimsical composition, his bandmates were, by many accounts, skeptical. The genius lay not in the song’s literary depth, but in its harmonic openness and rhythmic propulsion, which the band and Podolor recognized as a canvas for their expansive sound.

The track’s sound is built on a massive foundation of rhythm section work, a muscular groove that sits right on the edge of a gospel-rock fervor. The bass line is propulsive, a relentless lockstep with the drums. Over this, a clean, bright electric guitar churns out simple, driving power chords. Crucially, the piano serves less as a melodic instrument and more as a percussive glue, its bright, compressed timbre filling the middle frequencies and pushing the rhythm forward with staccato chords.

The arrangement swells through judicious use of dynamics. Listen closely to the way the verses are relatively contained, riding on Chuck Negron’s soaring but controlled lead vocal. The texture is lean, almost conversational, before the pre-chorus signals the coming shift. Then, the collective voice hits.

The Voice: A Cathedral of American Rock

The moment the famous chorus explodes, it’s not just an increase in volume; it’s an eruption of democracy. Three Dog Night’s distinctive multi-vocal attack—a white-soul harmony tradition applied to rock—is what makes this track truly monumental.

In that “Joy to the World” chorus, the three singers weave a tightly-coiled knot of harmony that elevates the absurd lyrics into something genuinely spiritual. The lead voice is pushed to its absolute limit, thrillingly close to breaking, while the backing voices provide a harmonic cushion that is simultaneously tight and gloriously uninhibited. This contrast between the precise, controlled verse and the cathartic, almost reckless chorus is the engine of the song’s “joy.” It’s a moment of collective catharsis that transcends the initial silliness of the bullfrog and the wine. The sheer sonic energy demands a physical response.

“It is a sound of glorious, unselfconscious release, an invitation extended from the studio floor to every listener.”

This is the kind of recording that makes the argument for high-fidelity premium audio equipment instantly compelling. You need speakers capable of separating those densely layered vocals and reproducing the transient attack of the rhythm section without losing definition in the midrange. When the song hits its stride, it is one of the most dynamic pop tracks of its era, capturing an ecstatic peak that few three-minute singles ever achieve.

The Long Echo of a Simple Song

The song’s simplicity proved to be its eternal strength. It arrived at the close of a decade marked by complex, psychedelic arrangements and concept albums. “Joy to the World” was a pure, unvarnished shot of optimism. It was a refusal to be heavy, even in heavy times.

I once spent a summer afternoon observing a group of guitar lessons students attempting to tackle the song’s main acoustic riff. They struggled not with complexity—it’s deceptively simple—but with capturing the original’s swagger, the feel that separates a clean sequence of notes from a powerful, driving groove. It’s a reminder that the best music relies on attitude and collective feel, not just notes on a page of sheet music.

A few years ago, I was driving late through a small desert town in the American Southwest. The local radio station, barely pulling in on the car stereo, played “Joy to the World.” It was the middle of a mundane Tuesday, no party, no ceremony, just the endless highway. Yet, for three minutes, the song transformed the isolated stretch of asphalt into an instant celebration. This is the ultimate proof of its staying power. The song has become an indelible part of the soundtrack for everything from athletic victories to cinematic moments of simple elation.

Its success vaulted Three Dog Night to the pinnacle of their career, cementing their reputation as the greatest interpreters of the early 70s. They proved that commercial rock could still possess the raw vocal grit of soul music and the immediate hook of pop, all while delivering a message—however nonsensical its source—of pure, unadulterated happiness.

“Joy to the World” is more than just a hit record; it’s a testament to the power of a committed group of musicians breathing explosive, vital life into an unlikely composition. It is a siren call for collective exuberance, a masterpiece of arrangement that remains, fifty years on, impossible to resist. Give it another focused spin tonight. You might find a layer of pure, unadulterated joy you missed before.

Listening Recommendations

- “Never Been to Spain” – Three Dog Night: Another brilliant Hoyt Axton composition from the same Naturally album, showcasing the band’s versatility in interpreting outside writers.

- “Signs” – Five Man Electrical Band: Shares the same early ’70s feel of socially aware rock filtered through a polished, but still gritty, production style.

- “Vehicle” – The Ides of March: Features a similar brassy, energetic rock arrangement and a triumphant, instantly recognizable melodic hook.

- “Listen to the Music” – The Doobie Brothers: Epitomizes the same kind of positive, harmony-drenched, guitar-driven pop-rock sound that was soaring up the charts shortly after.

- “Put a Little Love in Your Heart” – Jackie DeShannon: Captures a similar mood of simple, declarative, and infectious optimism delivered with a powerful, soul-inflected vocal.