I first hear it the way most people remember it: on a car radio that sounds like it’s been lived in. The drums don’t so much enter as fall forward. A bright, brazen vocal leans over the beat, and the whole thing moves with the confidence of a kid sneaking past curfew. “Hanky Panky” isn’t shy about what it wants to be. It’s a grin set to tape—a three-chord dare that locks into a stomp and refuses to apologize for how simple it is.

Before we talk about charts and labels and the long shadow of garage rock, it’s worth sitting with the recording itself. The performance feels live, almost tipped toward chaos, with the rhythm section pushing air like a budget PA in a crowded hall. You can hear the room—tight, unadorned, the sort of space where every cymbal hit smears a little and every vocal yelp blooms into quick echo. The tempo is urgent but not frantic, the backbeat thick and unvarnished. When the hook lands, it lands as something obvious, as if you’ve known it since grade school and only needed a drummer brave enough to say it out loud.

Context sharpens that instinct. “Hanky Panky” was written by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, first tucked away on a Raindrops B-side in 1963—a Brill Building trifle waiting for a spark. Many sources note that Tommy James first cut it in 1964 with an early Shondells lineup for the tiny Snap label, where it did regional business and then faded. The story turns on a Pittsburgh bootleg: local DJs spun a revived pressing in 1965–66, and the track suddenly caught a second life so potent that James needed a new band to ride it. Roulette Records swooped in, and the reissue raced up the U.S. charts to No. 1 in July 1966. michiganrockandrolllegends.com+2Wikipedia+2

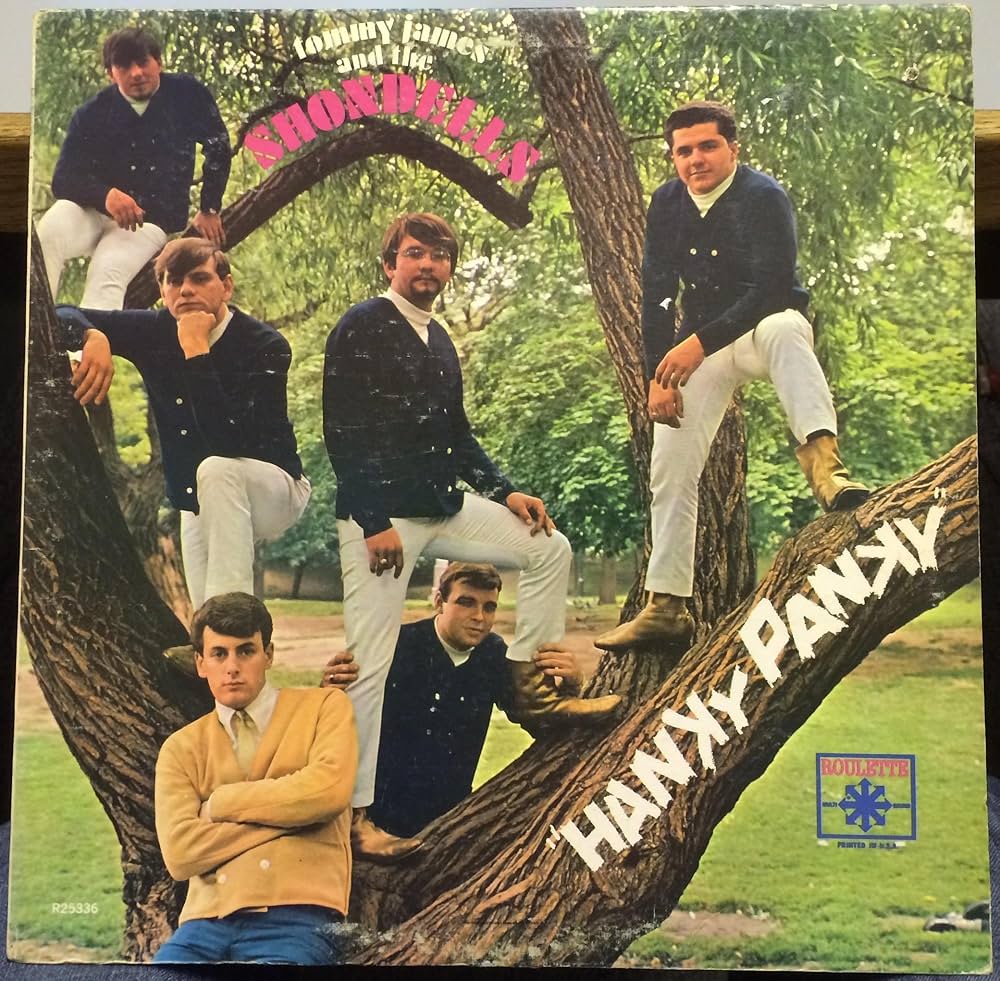

Place it in the career arc and it gets even clearer: “Hanky Panky” becomes the hinge that swings Tommy James from midwestern obscurity to national profile. The cut anchors the group’s debut LP—titled Hanky Panky—released the same year on Roulette. Production credits across the single and LP point to Henry Glover, with Bob Mack also credited on the LP, which fits the music’s mix of on-the-floor immediacy and radio-savvy trimming. The record broke the door open; within a few years, James would stretch toward polish (“I Think We’re Alone Now”) and psych gloss (“Crimson and Clover”). But the blueprint is here: a knack for choruses that come on like a chorus line and a showman’s willingness to ride the first great idea straight to the tape head. Wikipedia+1

This is a piece of music that earns its reputation by refusing to overcomplicate the obvious. The arrangement is sturdy: drums that stomp, bass that walks in straight lines, and a trebly guitar figure that slices through like chalk on pavement. There’s no orchestral padding, no filigreed strings or woodwinds dressing up the skeleton. The pleasure is the skeleton: kick, snare, bass, voice. The attack is crisp, the sustain short—every chord feels like it has somewhere to be.

Listen to the vocal phrasing. It’s half shout, half wink; the intonation is purposefully rough, a singer making the microphone a conspirator rather than a confessional. Reverb trails are quick, suggesting a small room and a board that isn’t trying to hide the bleed. If you turn it up on decent speakers, the cymbals smear at their edges and the tambour (if it’s there) rides just under the vocal, the sort of mix choice that makes the groove feel like someone tapping your sleeve. This is the kind of single that tells you exactly what the dance floor should do without ever bothering to say please.

One of the enduring myths around “Hanky Panky” is that it’s a song that “just happened.” That’s both true and a little unfair. Yes, it rides a bootleg wave and leans into an unfussy performance. But that looseness rests on precision choices. The verse cadence leaves negative space the band can pounce on; the hook repeats right as the ear starts to wander; the whole thing pivots on a rhythmic see-saw—push, pull, push—that’s deceptively tricky to nail. Amateurish? No. It’s businesslike about sounding tossed-off, which is as professional as it gets.

And yet, “Hanky Panky” also sits at a cultural seam. In 1966, American radio straddled tidy pop and fuzzier, club-bred textures. This single parks itself in the middle. You can file it with garage staples, but it’s equally at home alongside polished Brill Building confections. That dual identity is part of why it still feels usable by listeners’ lives—soundtracks for spontaneous detours, scrimmage warmups, backyard parties where somebody finds an extension cord and the evening turns.

Consider three quick vignettes.

First: a late-night drive after a too-long shift, windows cracked, road noise braiding with the intro drum hits. You’re too tired for narrative and too wired for quiet; this track presents itself as a solution. At 2-plus minutes, it’s concentrated caffeine. The hook hits, you grin despite yourself, and a service-station neon flickers by like it’s keeping time.

Second: a college bar twenty minutes before last call. The jukebox is a democratic mess—current rap, sad-country sing-alongs, a Britpop chestnut—until someone with good instincts queues “Hanky Panky.” Its stomp cleaves the room cleanly: dancers rise without planning to, and the wall-leaners suddenly look like they picked the wrong shoes.

Third: a kitchen on a Saturday morning, sunlight across the tile, the record spinning while someone burns the first round of pancakes. The imperfections of the recording feel companionable. The handclaps (real or imagined) make the room feel bigger. Sudden laughter lands right as the chorus does.

“Sometimes the most durable pop isn’t polished like chrome; it’s scuffed just enough to sound like your life.”

The technical ear has plenty to admire. The drums are up in the picture, especially the snare, which pops with a dry crack. The bass is supportive rather than melodic—more sinew than melody, a choice that keeps the chorus from turning syrupy. The vocal sits forward, almost over-loud by modern standards, which adds to the sense that we’re hearing a performance rather than a construction. If there’s a keyboard at all, it’s tucked deep; the track is practically a textbook case of what happens when you let the rhythm section build the house and trust the singer to throw the party. A lone piano would have complicated the midrange, but the arrangement leaves that space for voice and drum transients.

As a debut statement on Roulette, “Hanky Panky” also had to demonstrate something beyond a single. The LP that bears its name is a collection of period-appropriate beat numbers and covers, but even skeptics concede the title track has that particular radio-ready voltage. The LP credits point to Bob Mack and Henry Glover in the producer’s chair—a pairing that tells you plenty about the priority: keep the edges, frame them just enough, and deliver a cut that can spar in a playlist with British Invasion riffs and American girl-group echo. The song’s origin—the Barry/Greenwich pen—ties it back to a writing tradition that knew how to turn the smallest phrase into a dance instruction. Wikipedia+1

One reason “Hanky Panky” endures is that it’s modular. DJs, from 1960s ballrooms to present-day retro nights, can slot it anywhere tempo-wise. Bands can cover it without a rehearsal marathon. And listeners can map whatever mood they need onto it: flirtation, mischief, just-enough-defiance. Strip away the words, and you’re left with a groove architecture so basic you can teach it in five minutes.

When people call it “garage,” they often mean the texture more than the genealogy. The recording sounds like affordable microphones aimed quickly, preamps pushed to the point where drum attacks get a little square at the corners. When Tommy James hits the hook, there’s a quick lift in the reverb—the kind of serendipity you get when a singer leans a few inches closer to the mic and the engineer rides nothing at all. That aura—control surrendering to immediacy—is hard to fake. Even in an era of infinite takes, bands still chase this particular lightning.

Let’s talk sequence within the LP experience. Many listeners encounter “Hanky Panky” first, then wander the set to find other affinities. You can hear the band learning on-mic: the straight-ahead stomp reappears in variants, the harmonies tighten track-to-track, and you get the sense of a group moving quickly to bottle a moment that might not last. That urgency suits the era. If you wanted a meticulous studio symphony, 1966 offered plenty of choices. If you wanted a single that sounded like Saturday night inside a Wednesday afternoon, this was it. The LP’s second single, “Say I Am (What I Am),” would climb respectably as well, but the title track is the reason the door opened. Wikipedia

There’s also the business story. Roulette Records could move quickly and had the muscle to get spins. The label loves a Cinderella tale: a found single, a reconstituted band, a chart run that looks inevitable only in retrospect. The bootleg-to-Boardwalk pipeline is part of rock lore now, but in 1966 it felt like proof that regional taste could still co-author the national playlist. The Pittsburgh catalyst—DJs and promoters resurrecting a forgotten local disc—reads like a parable about curiosity. Without a crate-digger and a dancefloor, “Hanky Panky” might have stayed a footnote. Instead, it becomes the headline. michiganrockandrolllegends.com

What does it feel like in high fidelity? The honest answer: cleaning it up too much can sand off its grin. You can absolutely appreciate it through modern studio headphones, but the charm peaks when the mix breathes a little and the imperfections turn aerodynamic. Meanwhile, the track flows just fine within a modern playlist, even if it’s separated by half a century from its neighbors. It sits comfortably beside glam, early punk, even power-pop—the universality of a square-beat stomp.

Instrumentation talk often drifts toward guitar heroics, but this isn’t that kind of record. The guitar is a rhythm tool first, carving the beat’s angles, leaving the melodic spotlight for the voice. A keyboard cameo would have pulled the track toward a different lineage; mercifully, any possible piano color is minimal, which keeps the cut taut. The sonic palette is small, and that’s the point. You can imagine a cavern of overdubs, but “Hanky Panky” would melt under the weight. The band gives you the blueprint and trusts your body to furnish the rest.

If you come to “Hanky Panky” looking for a lyrical thesis, you’ll miss the larger thesis: motion. This is music as social physics—mass times acceleration. The lyric rides the beat; the beat drives the body; the body, once in motion, needs only the next snare hit to keep going. In a mid-60s landscape that sometimes prized cleverness over contact, “Hanky Panky” insists on contact. It’s not careless; it’s careful about joy.

A brief detour through the origin helps underline that claim. Barry and Greenwich wrote with a feel for phrases that fit a teenager’s mouth and a DJ’s clock. The earliest Raindrops version had the bones; James and crew supplied the swagger and the room noise that made it feel inevitable. Add local DJs, a bootleg pressing that sped the track slightly, and the commas between events start to vanish. What remains is a single that sounds like it arrived instantaneously—because for the listener, it always does. michiganrockandrolllegends.com

There’s a temptation, writing about 1966, to over-solemnize. The year was full of heavy art and big ambitions. “Hanky Panky” doesn’t reject that; it just proposes another path to durability. Joy can be archival. Groove can be a thesis. And sometimes the shortest way to memory is the most direct beat on the kit.

For collectors, the Roulette pressings and reissues offer a small history in their labels and credits—one more reminder that paperwork follows magic, not vice versa. For casual listeners, the whole history folds into a single sensation: that chorus arriving like a friendly shove between the shoulder blades. You don’t analyze it first; you move.

If you’re encountering this track anew in a curated playlist or via a music streaming subscription, give yourself the courtesy of a second spin. The first run is for surprise. The second is for noticing the miniaturist choices: how the drummer places the snare just behind the metronome, how the bass stays monastic until the chorus, how the vocal glances off the reverb return and smirks. Those are the moments that keep a radio single alive long after the signal fades.

By the time the fadeout arrives, you’ve been reminded of something deceptively simple: a song doesn’t need to be epic to be permanent. “Hanky Panky” survives because it respects the smallest durable unit of pop—pulse, hook, voice—and makes each element earn its keep. That’s why a record born in a regional scene, pressed and re-pressed, scraped into national consciousness, still feels like a secret handshake. You hear it, and the room sharpens.

The last measure falls away like a door closing softly. You don’t clap; you grin. Then you start it again. Because modesty, when it’s this sure of itself, is irresistible.

Recommendations

— The Kingsmen – “Louie Louie” (Raw, chant-driven garage energy and a perfect companion to a two-chord stomp.)

— The Troggs – “Wild Thing” (A 1966 masterclass in minimalism: primal beat, unabashed swagger, and a chorus you can’t shake.)

— The Standells – “Dirty Water” (City-grit attitude and fuzz-tone riffing that mirror the rough-edged charm.)

— The McCoys – “Hang On Sloopy” (Handclap pop with a dancefloor-ready tempo and airwave-friendly hook.)

— The Kinks – “You Really Got Me” (Proto-hardness and clipped phrasing that set the template for unvarnished riffs.)

— The Monkees – “I’m a Believer” (Brill Building sparkle channeled into exuberant radio pop, kin to the song’s writerly roots.)

Facts & Sources: “Hanky Panky” written by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich; early Raindrops B-side (1963); Tommy James’ 1964 regional release on Snap; revived via Pittsburgh bootleg; Roulette reissue reached U.S. No. 1 in July 1966; LP and production credits to Henry Glover (single) and Bob Mack/Henry Glover (LP).