The year is 1962, a restless pivot point in American music. The ghosts of the pioneers were still rattling the chains of rock and roll, but the first whispers of the British Invasion were on the wind. It was a moment of deep sonic transition, a space where a young Atlanta songwriter working as an electrician could, almost by accident, land a sound that was both a tribute and a prophecy. This is the moment Tommy Roe’s “Sheila” arrived.

I first encountered this piece of music not on the crackling tube radio of its era, but decades later, pouring out of a dusty, rebuilt jukebox in a roadside diner. The song’s simplicity, the sheer, unbridled energy of its two-minute runtime, was disarming. It felt like an artifact perfectly preserved, a vibrant, primary-colored photograph from a simpler time. Yet, beneath the obvious teen-idol shimmer lay a sophisticated piece of sonic engineering, a deliberate echo built for the present.

Roe had first recorded this song—originally titled “Sweet Little Frieda,” written about a high school crush—in 1960. That initial attempt, while promising, failed to gain national traction. The crucial re-recording, the one that became a global phenomenon, came in 1962 for ABC-Paramount, helmed by a producer who would become an essential figure in rock and country: Felton Jarvis.

Jarvis, reportedly, recognized the vacuum left by the tragic loss of Buddy Holly in 1959. He had a clear sonic strategy: lean into the “Lubbock Sound.” The result was a Nashville session that gave us the iconic texture of this hit. The backing band included heavyweight session players like Jerry Reed on guitar, and the inimitable Jordanaires providing the smooth, ghostly harmonies that counterpoint Roe’s hiccuping vocal delivery.

The most defining characteristic of the 1962 arrangement is the drumming. It’s a relentless, tight, almost tribal rhythm that is impossible to ignore—a distinct paradiddle pattern that is an unmistakable nod to Holly’s masterpiece, “Peggy Sue.” This hyper-focused percussive attack anchors the entire song, providing a jittery, propulsive tension that propels the vocal forward. It’s what elevated the song from a regional rockabilly ballad to a transatlantic chart-topper.

Roe’s vocal performance is a masterclass in controlled, youthful exuberance. He sings of “Sweet little Sheila,” with blue eyes and a ponytail, employing a slight, noticeable Southern twang and those trademark vocal tics—the brief, almost nervous catches in his throat—that directly evoke the late great Buddy Holly. This similarity was intentional, a calculated risk by Roe and Jarvis that paid off handsomely. It wasn’t merely imitation; it was a continuation, a respectful spiritual inheritor to the early rock sound.

The instrumentation is sparse but effective. The rhythm guitar cuts through with a bright, clean timbre, providing a choppy, up-tempo accompaniment to the drums. You can almost feel the thick gauge strings and the single-coil pickups vibrating. While a piano part was reportedly played by Nashville legend Floyd Cramer on the session, it is largely submerged in the final mix, serving more as a foundational texture than a melodic voice, a common practice in those efficient, rapid-fire country-rock sessions.

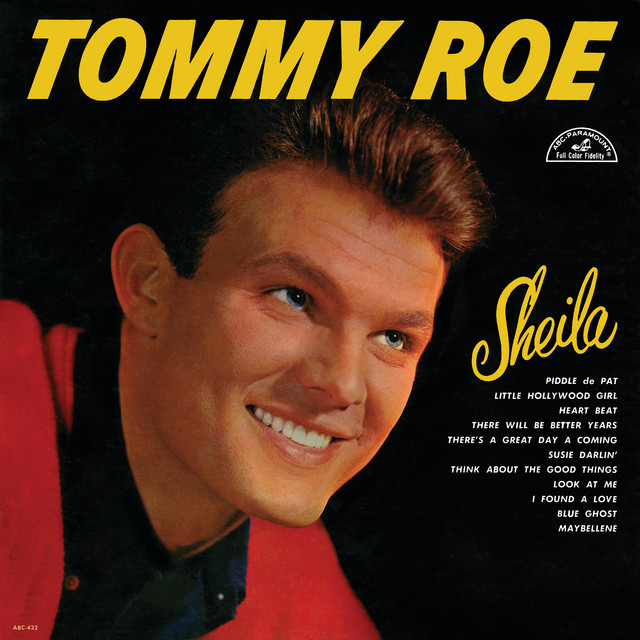

“Sheila” became the centerpiece, and title, of Roe’s debut album later that year. Its success was astounding, quickly climbing to the number one position on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 and charting strongly around the world. It launched Roe’s career, forever cementing him—sometimes reluctantly, sometimes embraced—as one of the principal architects of the pre-Beatles teen-pop sound. It was an immensely lucrative single, though it was years later, in 1969, that the RIAA presented him with a gold record for its accumulated sales of over a million copies.

The contrast here is fascinating: a sound that felt old-school to the ears of 1962 was simultaneously so fresh and immediate that it broke through. It managed to charm the traditionalists while providing a template for the effervescent, hook-driven pop that would soon be derisively labeled “bubblegum.”

Today, when we listen to “Sheila” through high-quality premium audio equipment, its clean production values—for the era—shine. The reverb on Roe’s voice is warm and enveloping, lending a cinematic quality to his simple, earnest confession of love. It’s a song about a girl so captivating, her name “drives me insane.” The entire piece is over in just a little over two minutes, a breathless sprint that is the very definition of a perfect single. It leaves no room for fat; every element serves the hook.

Imagine a teenager in 1962, hearing this for the first time on the radio. They’ve just gotten home from school, flipping through the sheet music they bought for the latest chart hit, and suddenly this driving, happy sound fills the air. It’s an infectious call to the dance floor, a soundtrack for first glances and nervous conversations. It feels simple, yet it is powerfully constructed to stick, to burrow into the consciousness.

“The power of ‘Sheila’ lies not in innovation, but in perfect distillation—the raw urgency of the past polished into a pop gem for the future.”

The song’s cultural wake is also worth noting. It was so potent that the French singer Annie Chancel, who covered the song later that year, adopted ‘Sheila’ as her professional pseudonym and became one of the biggest pop stars in France. The essence of the song—catchy, driving, deeply romantic—proved entirely translatable.

What remains is a pure, concentrated hit of pop brilliance. It’s a song that exists outside of the rigid categories we later impose. It’s rockabilly revivalism and proto-bubblegum. It’s Nashville session musicians channeling Texas-born brilliance. It’s a two-minute slice of pure, unadulterated musical joy. Put it on, and try to keep your foot still. It’s impossible.

Listening Recommendations (For Fans of the ‘Sheila’ Sound)

- “Peggy Sue” – Buddy Holly (1957): The clear spiritual and rhythmic blueprint for “Sheila,” sharing the driving drum pattern and vocal hiccups.

- “Travelin’ Man” – Ricky Nelson (1961): Shares the clean, professional, pop-friendly version of rock and roll common just before the major British impact.

- “Palisades Park” – Freddy Cannon (1962): Another perfect, propulsive two-minute slice of early ’60s energetic pop with a similarly driving beat.

- “The Loco-Motion” – Little Eva (1962): Features that same bright, clean production sound and infectious, dance-driven energy of the period.

- “Let’s Twist Again” – Chubby Checker (1961): Exhibits the same kind of stripped-down, rhythm-forward, irresistible pop construction.

- “Hey! Paula” – Paul & Paula (1963): A transition to the slightly sweeter, more sentimental side of early ’60s pop, but with comparable clean vocals and arrangement.