I first heard “Amarillo By Morning” not on a pristine stereo, but on a jittery late-night station that faded in and out between county lines. The song didn’t insist on itself; it stretched out like highway, fiddle leading the way, George Strait’s voice clean and unhurried. The hook drifted past billboards and cattle guards, and I remember thinking: this isn’t just a rodeo story—this is a map of how some lives must be lived, with bruised hands on the wheel and a sunrise that keeps moving the finish line.

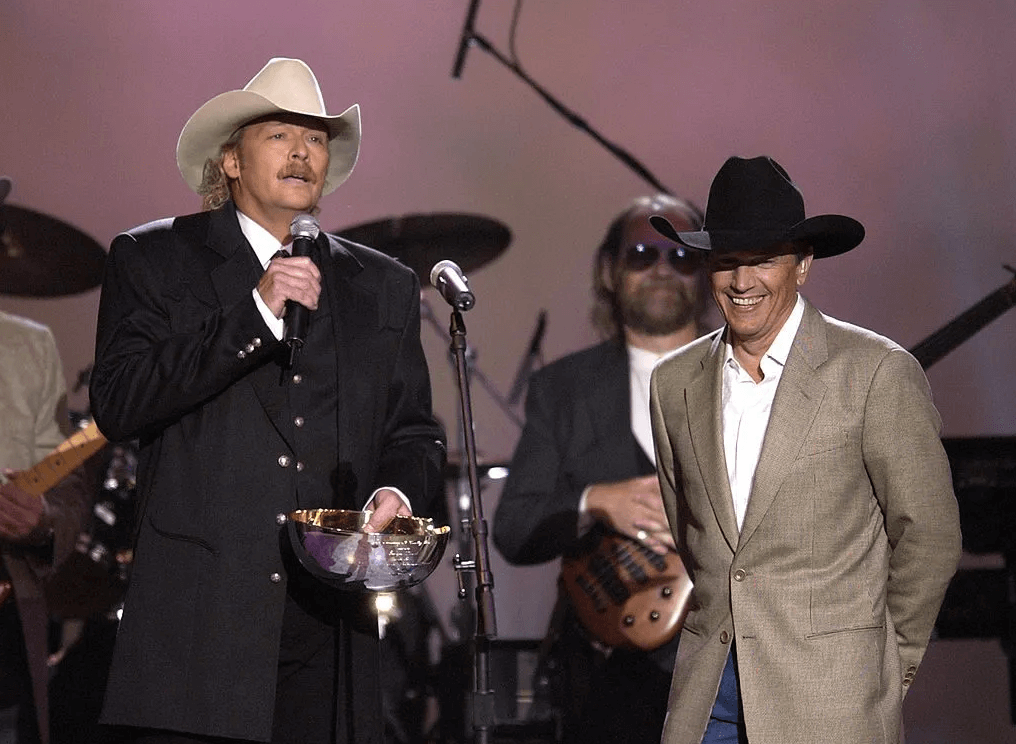

The official credit at the heart of the matter belongs to George Strait. His version, produced by Blake Mevis for MCA Records, appeared on the 1982 album “Strait from the Heart” and was released as a single in 1983. Written by Terry Stafford and Paul Fraser, the song had an earlier life in Stafford’s original 1973 recording, but Strait’s cut became the defining reading, a top-five hit on the country charts and a durable entry point for listeners who treat the tune like a rite of passage. Alan Jackson didn’t release a formal studio duet of “Amarillo By Morning” with Strait; instead, he stands as a stylistic neighbor who has performed or nodded to it live over the years—one of those lineage moments where the apprentice has long since become a master, yet still tips his hat.

What anchors the piece of music is its arrangement: a bright, singing fiddle line that announces the horizon and never lets go. The rhythm section is spare and steady, a soft gallop rather than a stampede. Acoustic and electric guitar work in tandem—one providing percussive strum, the other tracing liquid fills that feel like fence lines slipping past the window. The pedal steel hangs in the air with restraint, not drowning the space but tinting it, as if the room itself were steeped in old varnish. A few piano chords tuck in near the verses, understated, chiming at the edges like lights on a distant exit ramp.

The production feels open, almost hand-hewn. Strait’s vocal sits high and unadorned, with what many sources note as a subtle plate reverb that never pulls focus. You can hear the syllables land with the surety of boots on plywood. There’s no grand crescendo because the work of the song is in its steadiness, its refusal to cheat with drama. Country music has plenty of big endings; this one is about holding the line until the morning shows up.

As a text, the narrative is simple: a rodeo man running down dreams and paydays, losing things he can’t afford to lose, and showing up again in Amarillo because there’s always another ride. Yet the emotional shading is richer than the plot suggests. Even without an explicit confession, you can hear the costs tally up—the cracked knuckles, the towns that blur together, the lovers who find the waiting more dangerous than the bulls. Strait’s phrasing moves between stoic and tender, hitting consonants squarely and letting the vowels bloom. He sounds like a man who doesn’t waste words, which is probably why every word counts.

Alan Jackson’s role here is atmospheric but meaningful. He belongs to a generation that absorbed Strait’s ‘new traditionalist’ clarity and carried it into the 1990s and beyond, keeping fiddle and steel at the center even when radio flirted with pop sheen. When Jackson nods toward “Amarillo By Morning” onstage—or stands next to Strait in other contexts—you’re reminded that certain songs aren’t just repertory pieces; they’re handshakes across eras. If you’ve ever watched Jackson cover it, you see how the melody fits his baritone like a familiar jacket, austere but warm.

“Amarillo By Morning” is also a study in dynamic modesty. The mix breathes without calling attention to itself. The fiddle’s attack is crisp, but the sustain is silky, and when the steel lets a note taper, you can almost measure the reverb tail in inches. The drums sit soft in the pocket—no gated thwack, just an organic thump that keeps the wheels rolling. Listen closely to the way the guitars trade small gestures: a clipped phrase here, a brushed harmonic there, the sort of details that only surface after the twentieth play. This is music engineered for endurance rather than spectacle.

Three vignettes keep returning to me when I think about why this song still lands.

First: a dad driving an aging Silverado before dawn, thermos rattling in the cup holder, his teenage son dozing in the passenger seat. They’re headed to a small-town arena where the kid will ride steers for the first time. The radio offers advice the dad doesn’t say out loud: it won’t always go your way, but show up anyway.

Second: a nurse finishing a graveyard shift, keys to a quiet apartment dangling from tired fingers. She doesn’t know anything about rodeo, but she knows about mornings that arrive like judgment. When Strait sings about being broke, she smirks at the ceiling of her car and thinks, “Buddy, I’ve been there,” and waits for the chorus to wash the night off her.

Third: a college kid in a city far from home, headphones on, walking past bakery steam that fogs the winter air. He’s never seen Texas, but he recognizes the hunger in the melody. Some songs offer destinations; this one offers a direction.

If you’re searching the track for lyrical flash, you won’t find much. That’s the secret. The words are worked into the grain of the melody, as if the language existed primarily to hold the note. Strait never over-sells the pain. He underlines the resolve. The timbre of his voice—clear, unforced, with a hint of west-Texas dust—feels engineered for lines that accept what they cannot change. You don’t need a weeping string section to feel the ache; two bars of fiddle will do.

What’s striking is how modern the record still sounds, given that it bears the hallmarks of early-80s Nashville. The EQ choices give the fiddle and steel a glassy brightness without harshness. The low end is conservative, which leaves room for vocal intelligibility; you never miss a consonant. Played on a quiet room system or in a truck with road noise, the balance holds. It’s the rare country single whose “premium audio” virtues reveal themselves without a thousand-dollar rig; even better, the song remains humane through the smallest phone speaker.

When we talk about George Strait’s career arc, this single becomes even more consequential. “Strait from the Heart” established him as a standard-bearer of a sound that would outlast trends. Working with Blake Mevis, he refined the idea that tradition isn’t about nostalgia; it’s about choosing the right notes and trusting silence. The success of “Amarillo By Morning” solidified his path through the decade—hit after hit built on similar virtues. Alan Jackson’s arrival later would demonstrate how that map scales: keep the songs clean, the stories plainspoken, the players tasteful, and the audience will do the rest.

One beauty of the recording is its photography of space. You can almost picture the ensemble: fiddle up front, steel off to the right, the rhythm guitar near the singer, and the piano tucked behind a baffle. Whether or not that is literally how the room looked is beside the point; what matters is that the mix conjures place. You can sense air moving around the instruments, a sonic parallax where no element bullies the others. It’s a masterclass in leaving things out.

This is also a song that resists the urge to swell into a cinematic bridge or key change. Instead, it trusts the cycle of verse and chorus, much like a rider trusting the gait of a horse. The melody coils and releases without theatrics. The chorus lands not like a fireworks burst but like dawn slipping between blinds. When the last notes fade, it doesn’t feel like an ending so much as an arrival to the next long mile.

If you’re a musician looking to study its inner mechanics, notice how the chord progression keeps the harmonies familiar enough to feel like home while allowing small suspensions to create ache. There’s room to interpret the vocal lines with different textures—Strait favors cool clarity, while later covers sometimes lean into rougher grain. For players, the questions are practical: where to place the downbeat in your strum, how to let the steel halo the edges without swallowing the singer, whether the piano should sparkle on top or offer a lower, bell-like cushion. The arrangement answers these questions by example: be generous, not showy.

For singers, there’s a lesson in restraint. Strait’s phrasing obeys punctuation but never feels stiff. He bends just enough—the kind of micro-vibrato that suggests control rather than strain. He hits the center of the pitch and lets the emotional weight gather naturally. Many contemporary performers aim for vocal gymnastics; this song argues for the athleticism of patience.

There’s a practical dimension to the tune’s longevity. You can hear it in bars after softball games, at weddings where an uncle with a baritone requests it as a quiet slow-dance, on tailgates where somebody pairs it with coffee before a long haul. It’s a traveling companion, unflashy but faithful. The rodeo details give it color; the human stakes give it legs.

A final word on the “George Strait & Alan Jackson” pairing in your search field: while there isn’t an official, co-billed studio release of this title by the two, the thought experiment is instructive. Put them side by side and you notice how both men reject affectation. Jackson would likely keep the tempo close to Strait’s, perhaps giving the steel a hair more room, his voice slightly earthier. The shared DNA is taste, and the result—whether in a live tribute, a guest spot, or your imagination—just reaffirms how sturdily the song is built.

“Some songs knock; this one simply opens the door and lets the morning in.”

If you’re approaching the song as a learner, you’ll find that even basic chord shapes can carry the tune with dignity. Beginners practicing from available sheet music will appreciate how the melody sits naturally against open-position shapes, yet seasoned players can add grace notes that turn the predictable into the personal. And if you’re listening critically, a good pair of studio headphones reveals the interplay between fiddles and steel—little slides and scoops you might miss on the first hundred drives.

The tune holds a peculiar peace: it acknowledges hardship without borrowing sorrow. There are no villains, only choices and consequences. By the final chorus, you realize the singer isn’t chasing victory. He’s chasing continuity, the proof that he can keep showing up. That’s why the song keeps showing up for us. Each time life knocks us sideways, we look for the next city at dawn.

And when the last fiddle phrase dissolves, you’re left with a quiet that doesn’t feel empty. It feels earned. That’s Amarillo’s true gift—not a triumph or a tragedy, but a horizon you can face with your shoulders squared. Play it again, not to recapture the past but to recalibrate the present.

Listening Recommendations

-

George Strait — “The Cowboy Rides Away” — Similar stoic clarity and a graceful farewell mood anchored by steel and fiddle.

-

Alan Jackson — “Here in the Real World” — A kindred early-career statement where simplicity and sentiment share equal weight.

-

Randy Travis — “Deeper Than the Holler” — Traditionalist warmth with an understated vocal that prizes melody over fireworks.

-

George Strait — “Run” — A later-era cut that preserves space in the mix and lets the story carry the motion.

-

Keith Whitley — “I’m No Stranger to the Rain” — Weathered resilience delivered with immaculate phrasing and gentle steel.

-

Brooks & Dunn — “Neon Moon” — Lonesome glow, steady pulse, and a melodic line that lingers like a highway sign after dark.