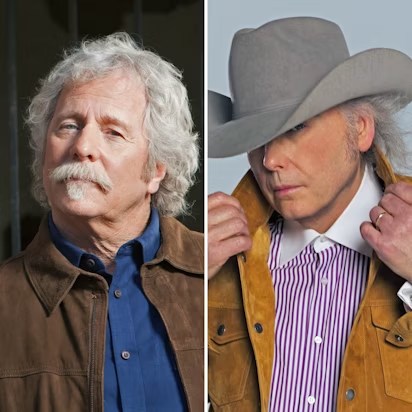

On August 23, 2025, something rare and quietly historic unfolded inside the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Beneath the banners of the critically acclaimed Western Edge: The Roots and Reverberations of Los Angeles Country-Rock exhibition, two architects of American roots music—Chris Hillman and Dwight Yoakam—sat side by side for an intimate, deeply reflective conversation.

It wasn’t just an interview. It was a summit meeting between generations. A passing of perspective. A reminder that in an era of streaming algorithms and genre-blurring playlists, authenticity still carries weight—and twang still cuts deep.

Moderated by veteran music journalist Erin Osmon, the discussion quickly transcended its promotional premise. What unfolded was a living archive of country-rock history, told not through nostalgia, but through lived experience. For fans of the Bakersfield bite, Laurel Canyon harmonies, and bluegrass precision, the evening felt less like a museum event and more like a revival.

Chris Hillman: The Quiet Revolutionary

To understand the magnitude of this conversation, one must first appreciate Chris Hillman’s place in American music.

As a founding member of The Byrds and later The Flying Burrito Brothers, Hillman didn’t simply participate in the birth of country-rock—he helped invent its DNA. Long before country crossover was a commercial strategy, Hillman was fusing bluegrass instrumentation with the electrified urgency of 1960s rock.

His early years as a mandolin prodigy grounded him in discipline and tradition. But Los Angeles in the mid-1960s was a crucible of experimentation. Folk met psychedelia. Country met rock. And Hillman, standing at the crossroads, had the musical vocabulary to bridge those worlds.

During the interview, Hillman spoke with understated clarity about those formative days. The Byrds’ groundbreaking fusion of jangling 12-string guitars and country storytelling wasn’t calculated—it was instinctive. When Gram Parsons later joined forces with Hillman in The Flying Burrito Brothers, the vision sharpened. Traditional pedal steel and honky-tonk ache were no longer background influences; they were front and center.

Hillman reflected on songwriting as craft, not commodity. He emphasized the discipline of musicianship, the importance of harmony—not just musical harmony, but interpersonal harmony within a band. “We were chasing a sound we believed in,” he noted, not one tailored to radio trends.

It’s that integrity that has kept his legacy intact. As Tom Petty once famously quipped, Hillman was the man who “at least paid for the fuel” every time a band like The Eagles boarded their private jet. The country-rock explosion of the 1970s—commercially dominated by others—was ignited by pioneers like Hillman who took the early risks.

Dwight Yoakam: The Rebel Revivalist

If Hillman represents the origin story, Dwight Yoakam embodies the resurgence.

When Yoakam emerged in the mid-1980s, mainstream Nashville had polished its edges. Production leaned slick. The Bakersfield sound—sharp Telecasters, punchy rhythms, emotional directness—felt sidelined.

Yoakam changed that.

With his tight jeans, cowboy hat, and unapologetic honky-tonk swagger, he brought California country roaring back to life. His breakout albums were steeped in Buck Owens and Merle Haggard influences, but they carried something contemporary and defiant. He wasn’t retro. He was revival.

During the conversation, Yoakam candidly discussed the early resistance he faced from Nashville executives who found his sound “too West Coast,” too raw, too reminiscent of an era they considered past. Ironically, it was Los Angeles—the birthplace of country-rock experimentation—that embraced him first.

He credited Hillman and his contemporaries for carving a path that allowed artists like him to exist outside Nashville’s gravitational pull. Hillman’s blending of folk-rock sophistication with country grit showed Yoakam that artistic boundaries were meant to be tested.

“I saw what Chris had done,” Yoakam reflected. “He made it possible to honor tradition without being trapped by it.”

That statement encapsulated the night’s deeper theme: innovation rooted in respect.

Mutual Respect Across Generations

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the evening was the visible admiration the two men held for one another.

Hillman praised Yoakam for igniting what he called a “country-rock resurgence” during the late 1980s and 1990s—a period when traditionalism needed a champion. Yoakam, in turn, credited Hillman’s generation for reshaping the musical landscape entirely.

It wasn’t flattery. It was acknowledgment of lineage.

In a music industry often driven by competition, their dynamic felt refreshingly collaborative. The student honoring the pioneer. The pioneer validating the successor. A continuum rather than a rivalry.

That generational bridge is precisely what Western Edge aims to illuminate. The exhibition traces the evolution of Los Angeles country-rock from the 1960s through the 1980s, spotlighting not only superstars but also the session players, songwriters, and producers who shaped the movement.

Both artists expressed gratitude for the museum’s meticulous attention to overlooked contributors. They spoke about the cultural alchemy of Los Angeles—a city geographically distant from Nashville yet spiritually connected to country’s storytelling core.

In L.A., country music absorbed new textures. It mingled with the singer-songwriter movement, brushed against psychedelia, and embraced studio experimentation. The result was a sound simultaneously grounded and progressive—dusty but refined.

Why the Western Edge Still Matters

The title of the exhibition—and the evening’s central metaphor—feels especially relevant in 2025.

The “Western Edge” isn’t merely geographic. It represents artistic independence. It symbolizes musicians who stood at the margins of mainstream country and chose to create something honest rather than convenient.

Today’s musical landscape, shaped by streaming platforms and genre-fluid collaborations, often celebrates hybridity. Yet Hillman and Yoakam reminded the audience that true fusion requires deep understanding. You can’t bend tradition if you don’t first respect it.

For longtime fans, the conversation offered validation. For younger listeners discovering country-rock through vinyl reissues or curated playlists, it provided context.

Quality endures. Authenticity resonates. And craftsmanship outlasts trend cycles.

A Blueprint for Artistic Integrity

What makes both Hillman and Yoakam compelling isn’t merely their catalogs—it’s their consistency.

Neither artist chased every industry shift. Neither diluted their sound for temporary radio favor. Instead, they evolved without abandoning their core.

That blueprint—honor your influences, master your craft, collaborate sincerely, and trust the audience—may be the most valuable takeaway from the evening.

In many ways, the interview felt like a masterclass disguised as a conversation. It wasn’t loud or sensational. It didn’t rely on controversy. It relied on depth.

And depth, much like twang, lingers.

The Reverberations Continue

As the evening concluded, one thing was clear: country-rock is not a relic. It’s a living current within American music.

From indie Americana acts to mainstream country artists reintroducing steel guitars and stripped-down arrangements, the reverberations of Hillman’s and Yoakam’s work are audible everywhere.

Their dialogue at the Country Music Hall of Fame wasn’t just a look back—it was a reaffirmation.

The Western Edge remains sharp.

And in a world constantly chasing the next sound, sometimes the most radical act is returning to the roots.

For fans who believe music should feel earned rather than engineered, the Hillman-Yoakam conversation wasn’t just an event—it was a reminder that the heart of country-rock still beats strong, echoing from Bakersfield to Laurel Canyon and far beyond.

Two titans. One enduring legacy. And a genre that refuses to fade quietly into the background.