There are some songs that resist all attempts at critical dissection, not through complexity, but through sheer, radiant familiarity. They are the air you breathe during a certain season of life, the permanent fixture of every highway drive, the soundtrack to every backyard cookout where the cicadas are louder than the conversation. Van Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl” is exactly this kind of piece of music: a three-minute, three-chord bolt of pure, untarnished nostalgia, sun-drenched and humming with a specific, remembered joy. To listen to it now is not simply to hear a song, but to step into a collective American summer, one that perpetually hums with the memory of youth.

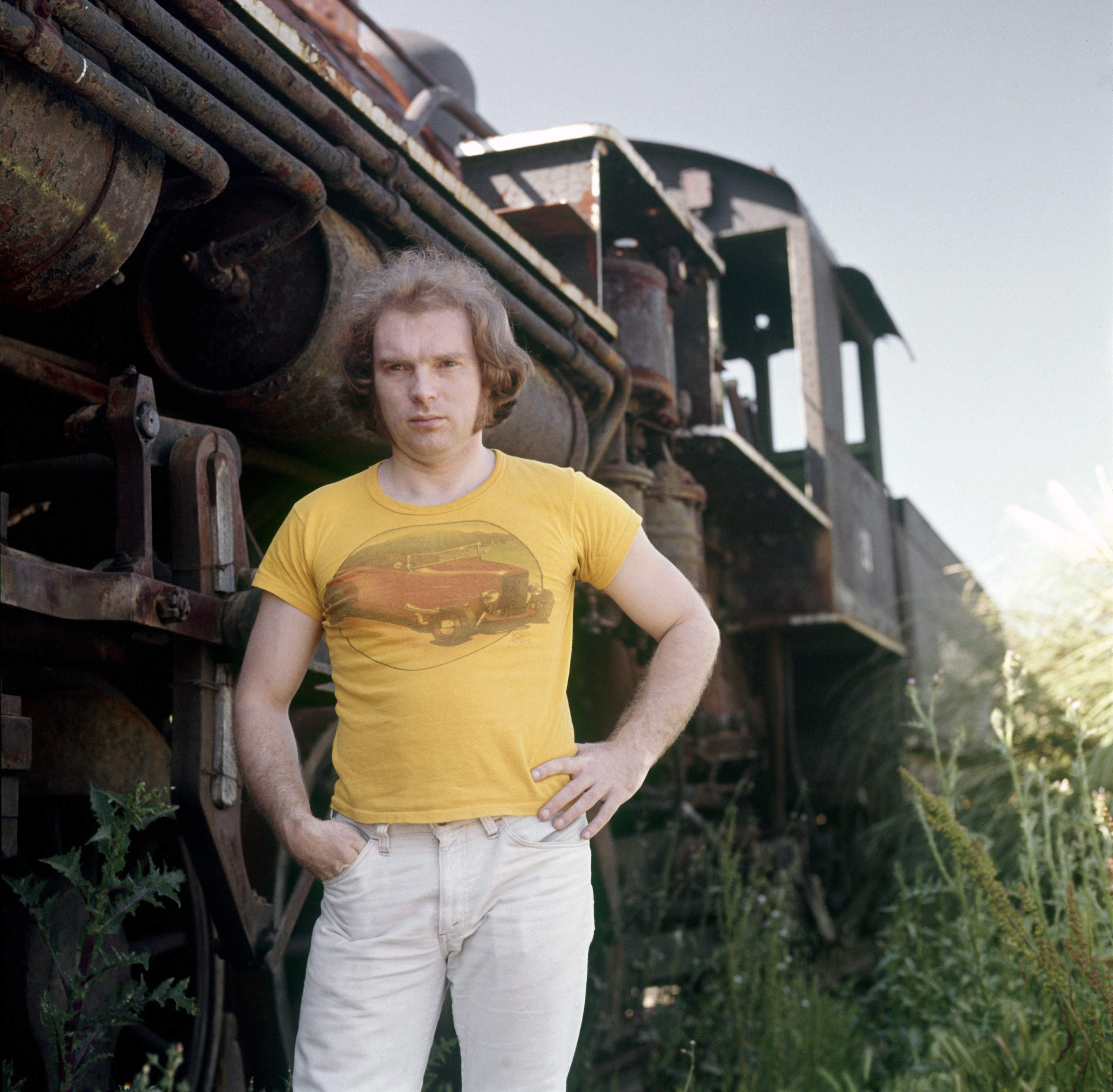

The strange beauty of this 1967 single is how it arrived, not as a seamless transition, but as a kind of reluctant bridge. Van Morrison had just emerged from the high-decibel, high-drama churn of his Belfast-born band, Them, having delivered garage-rock standards like “Gloria.” The 21-year-old was disillusioned with the industry’s grime and volume, only to be coaxed to New York by producer Bert Berns, a man who possessed a golden ear for radio hits, having already worked with Morrison on Them’s “Here Comes the Night.” Berns signed Morrison to his new label, Bang Records. The resulting two-day session, which spawned the collection that would be hastily compiled and released as the debut solo album, Blowin’ Your Mind!, was fraught, productive, and ultimately, foundational. Morrison famously disavowed the label and the LP itself, yet this single track, “Brown Eyed Girl,” remains his undisputed, perennial calling card—a pop song he tried, unsuccessfully, to outrun for decades.

The sonic architecture of “Brown Eyed Girl” is a masterclass in mid-sixties session-musician efficiency. It’s built on a spine of guitar and a rhythmic pulse that owes a clear debt to the calypso and Latin-tinged records producer Bert Berns adored. The sound is immediate, captured without the sprawling reverb or psychedelic wash of many of its contemporaries. This is music meant to be heard clearly, right now, blasting from a dashboard speaker.

The rhythmic backbone is deceptively simple. Gary Chester’s drums are crisp, driving the track with a clean, light-footed beat. Hugh McCracken provides the steady acoustic rhythm guitar, a foundational strumming that keeps the song grounded in its folk-rock undertow. The track is then elevated by Al Gorgoni’s memorable electric lead guitar, which is economical, bright, and responsible for the joyous, descending line that punctuates the choruses. It’s an instant-classic hook.

Filling out the lower-mid frequencies is Garry Sherman’s organ. It’s not a church organ, nor a blues B-3 growl; it’s a bright, tinny, almost circus-like tone, perfectly suited for the sunny disposition. The lack of a prominent piano line is notable, allowing the organ and the rhythm section to define the entire harmonic texture. Crucially, the gospel-tinged backing vocals provided by The Sweet Inspirations—a group that included Cissy Houston—lend a warm, soulful glow, transforming the boyish memory into something approaching the spiritual. It is this blend of New York session polish, calypso rhythm, and Belfast blues grit that gives the track its irresistible texture.

“The greatest pop songs don’t just recount a memory; they become the memory itself.”

The song’s central tension, and its enduring magic, lies in Morrison’s voice. At 21, he already possessed the world-weary rasp, but here it is infused with a youthful exuberance—a passionate, unrestrained yelp that explodes on lines like, “Do you remember when we used to sing… sha la la la la la la la la la la te da?” It’s a vocal performance of glorious, unselfconscious abandon. His phrasing is conversational and immediate, yet his sheer vocal power ensures that this casual reminiscence hits with the force of catharsis.

The lyrics, which famously underwent a minor but significant change in the title from “Brown-Skinned Girl” to the commercially safer “Brown Eyed Girl” (reports suggest the change was made in error on the tape box and stuck), are a wistful reflection on an adolescent, summer romance. They are a collection of sensory vignettes—the sun setting, skipping stones, the sounds of the radio, “making love in the green grass.” The last line was, of course, famously censored in a radio edit for being too suggestive for the airwaves, a detail that now feels absurdly quaint. The song is not explicit; it is tender. It is a poem about the realization that some moments, once lived, are lost forever.

The irony of this track’s enduring status is that it represents everything the later, more esoteric, jazz-infused Morrison rebelled against: the quick-hit pop single, the commercial constraint, the necessary compromise. Yet, it serves as the essential access point to his catalogue. It’s the moment the raw, untamed spirit of the Astral Weeks artist first flickered into the mass consciousness. The song peaked broadly within the Top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100, and has since gone on to become one of the most ubiquitously played songs of the 1960s, a testament to its democratic appeal.

For those considering getting their first setup for high-fidelity listening, the sonic complexity of a track like this, which hinges on the interplay between the rhythm guitar and the electric lead, truly justifies the investment in premium audio. It’s the kind of song that sounds passable on a tinny speaker, but unlocks a new dimension of warmth when heard through carefully calibrated sound, allowing the separation of the backing harmonies to truly shine. We also see the core structure of many great songs laid bare here, and it’s no wonder aspiring musicians often look for guitar lessons to master this particular blend of chords and rhythm.

Today, “Brown Eyed Girl” is less a song and more a cultural shorthand. It’s the track that gets pulled up when the road trip stretches late and someone needs a dose of pure, uncomplicated joy. It’s the wedding slow-dance that isn’t slow, a spontaneous burst of energy that connects generations. It’s the eternal echo of a time when innocence and adult experience first collided in a fleeting, unforgettable summer. It is perfect, three-minute melancholy disguised as pure, carefree abandon.

Listening Recommendations

- The Box Tops – “The Letter” (1967): Shares the urgent, soulful grit and efficient pop structure of a smash 1967 single.

- The Young Rascals – “Groovin’” (1967): Captures the same sun-dazed, easy-going romantic mood of a perfect summer love story.

- Aretha Franklin – “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” (1967): Features the powerful backing harmonies of The Sweet Inspirations, the same group on Brown Eyed Girl.

- Otis Redding – “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” (1968): Offers a similar wistful, almost melancholy reflection on a past love delivered with powerful, soulful vocal nuance.

- The Beatles – “Here Comes The Sun” (1969): Presents a comparable feeling of lightness and sheer, simple, uncomplicated optimism.