In country music, there are performances that entertain, and then there are performances that understand. When George Jones sang Merle Haggard’s “Sing Me Back Home,” it fell firmly into the second category. This was never about vocal fireworks or reinvention. It wasn’t a star taking on another legend’s hit to leave a personal stamp. It was something quieter, deeper, and far rarer: one life recognizing itself in another.

From the first note, Jones approached the song with a kind of emotional restraint that only the truly seasoned can afford. He didn’t rush the tempo. He didn’t build toward a dramatic crescendo. Instead, he let the melody breathe, allowing each lyric to settle into the silence around it. That space — those pauses between the lines — carried as much weight as the words themselves.

Merle Haggard wrote “Sing Me Back Home” from a place of confinement, inspired by his time in San Quentin and the stark humanity he witnessed behind prison walls. The song tells the story of a dying inmate requesting one last song, a memory of home carried on melody rather than freedom. It’s a piece rooted in regret, reflection, and the fragile dignity that can still exist in broken places.

George Jones, by contrast, sang it from the other side of survival.

By the time Jones recorded his version, he had already lived through his own battles — addiction, public struggles, near-career collapse, and hard-earned redemption. He knew what it meant to be trapped, even outside prison walls. He knew about the long road back, about facing your past without flinching. That shared understanding is what gives his performance its quiet gravity.

Jones didn’t treat the song like a showcase. He treated it like testimony.

His voice, famously one of the most expressive instruments in country music history, sounded different here — not flashy, not soaring, but worn in the best way. There’s a carefulness in his phrasing, as if he’s choosing each word because he has lived close enough to the truth behind it. He leans into the sadness without exaggerating it. He doesn’t cry for the listener; he simply tells the story and trusts the listener to feel it.

That trust is what makes the performance so powerful.

In an era when many artists might have tried to “update” the song or reshape it to fit their own persona, Jones did the opposite. He stepped aside. He allowed Haggard’s narrative to remain intact, honoring its emotional architecture rather than remodeling it. It feels less like an interpretation and more like a man stepping into an existing memory and walking through it gently.

There’s also a profound sense of respect in the fact that George Jones rarely recorded Merle Haggard’s songs. Both men were towering figures in country music, each with a distinct style and songwriting identity. For Jones to choose this particular piece suggests he recognized something deeply personal within it. He didn’t need to prove he could sing a Haggard song — everyone already knew he could sing anything. The decision feels intentional, almost reverent.

And that reverence shows in every line.

When Jones sings about the chapel, the dying prisoner, and the final request for a song from home, it doesn’t sound like storytelling from a distance. It sounds like memory. Like empathy forged through shared scars. There’s no sense of competition, no shadow of ego. Instead, the performance carries the emotional tone of one man nodding at another across time, saying, I understand.

That understanding transforms the song.

Under Jones’s voice, “Sing Me Back Home” becomes less about prison walls and more about the universal longing for grace at the end of a hard road. It’s about wanting to be remembered not for your worst mistakes, but for the part of you that still believed in something better. Jones knew that feeling intimately. His life had been a public lesson in falling and getting back up again. He sang the song like someone who knew how heavy freedom could feel when you’re carrying the past with you.

Musically, the arrangement stays understated, which only heightens the emotional impact. There’s no dramatic orchestration pulling the listener’s heartstrings. The instrumentation supports rather than leads, leaving Jones’s voice front and center. And in that simplicity, the truth of the song shines brighter.

Perhaps what’s most striking is how the performance refuses to beg for attention. It doesn’t demand tears or applause. It simply exists — steady, honest, and unadorned. In today’s world of vocal runs and high-production gloss, that kind of restraint feels almost radical. Jones reminds us that sometimes the most powerful thing a singer can do is not oversing.

Because real pain rarely shouts.

Listening now, decades later, the performance feels timeless. Not because it’s polished, but because it’s human. You hear age in his voice, history in his phrasing, and humility in his delivery. It’s the sound of someone who has stopped trying to impress and started trying to tell the truth.

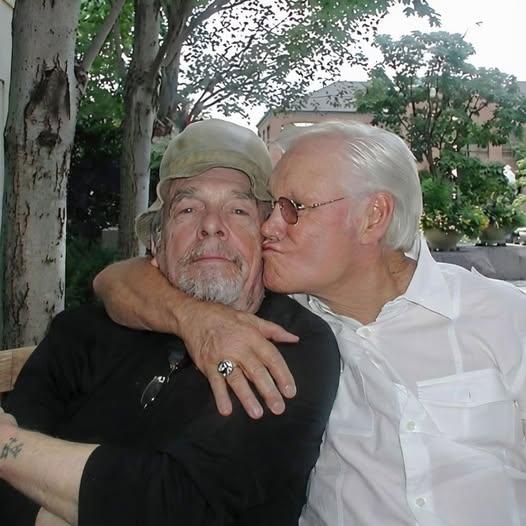

And that, ultimately, is what connects George Jones and Merle Haggard in this song. Both men built careers on honesty — on singing about flawed people, hard choices, and the complicated road between regret and redemption. When Jones sings “Sing Me Back Home,” it feels like those two life stories briefly overlap, meeting in a shared understanding that words alone could never fully explain.

It’s not a cover.

It’s not a reinvention.

It’s a quiet handoff of truth from one legend to another — carried on a melody strong enough to hold both their lives inside it.