The air in the cramped recording truck was thick, reportedly somewhere outside of Hollywood in late 1979. There was no orchestral sweep, no Nashville gloss—just the tightly wound energy of a road band that knew each other’s pauses, breaths, and restless hearts better than they knew their own beds. This wasn’t a studio session; it was a snapshot of an ecosystem. The executive producer of an upcoming film, Honeysuckle Rose, had asked Willie Nelson to write a theme song about the touring life. Short. Catchy. Something that felt like the diesel-fueled, two-lane-blacktop existence the movie was trying to capture.

Willie, legend has it, grabbed the nearest available scrap of paper—a barf bag on an airplane—and scribbled the lyrics. That origin story, gritty and perfectly unglamorous, is crucial to understanding why “On the Road Again” endures. It’s not an idealized travelogue; it’s a working man’s ode to his chosen tribe and the relentless forward motion of the wheels.

The Sound of Kinship: Anatomy of a Train Beat

When you strip away the iconography, you are left with a spectacular piece of music that succeeds on the strength of its arrangement and its relentless rhythm. This is a song that breathes with the collective lung of a touring ensemble, The Family. At its core is the famous “train beat”—a drumming pattern that mimics the churning, rhythmic clack of rail travel. The drums here, often credited to Paul English and/or Rex Ludwick, are dry, sharp, and propulsive, a machine-like bedrock for the whole affair. The snare is tight, almost military, driving the short runtime of just over two minutes with the efficiency of a tightly scheduled tour bus.

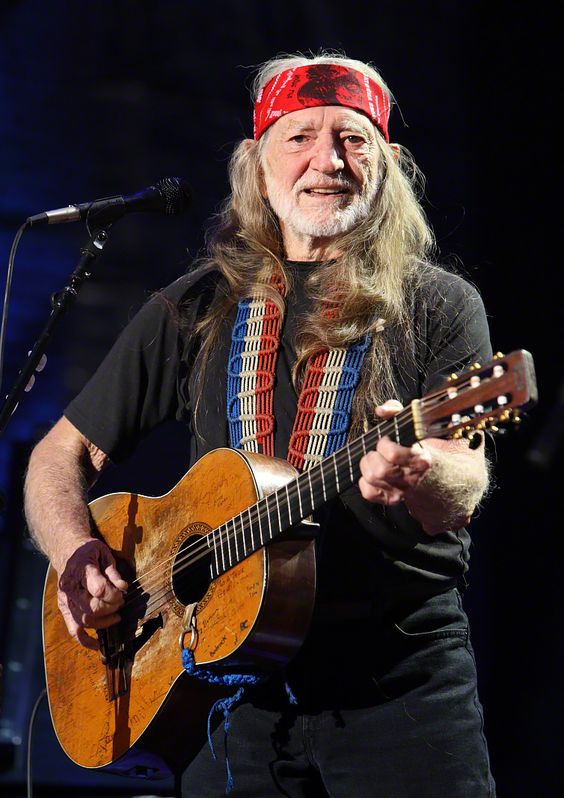

Over this kinetic foundation, the instrumentation is pure, distilled Willie Nelson. There is no soaring piano or layered backing vocal chorus to fill the space. Instead, the focus is drawn inexorably to the star and his battered classical guitar, the legendary Trigger. Willie’s nylon-string acoustic—already famous for its signature, resonant tone—is given a prominent role, its intricate, slightly loose solo feeling both technically marvelous and completely off-the-cuff. The attack is clear, the sustain minimal, leaving the space open and airy.

The bass, reportedly handled by Bee Spears, walks a playful line that manages to be both complex and utterly supportive, weaving around Nelson’s idiosyncratic phrasing. The arrangement is so uncluttered, so focused on capturing the essence of a live jam, that you can almost hear the dust motes dancing in the limited light of the Enactron Truck, the mobile studio where this track was largely recorded. The whole sonic profile is one of unvarnished immediacy, a testament to the raw skill of the players and Nelson’s self-production ethos for the soundtrack.

The Outlaw’s Homecoming: Career and Cultural Context

The release of “On the Road Again” in 1980 was a capstone, a triumphant signature moment for Willie Nelson’s already legendary career. This wasn’t a new beginning, but the absolute confirmation of his status as a country icon who had successfully broken the mold. Since his 1970s pivot to the “outlaw country” movement with seminal albums like Shotgun Willie and the breakthrough Red Headed Stranger, Nelson had fought for and won complete creative control. This track, the centerpiece of the Honeysuckle Rose album (a soundtrack that topped the Country charts), demonstrated his philosophy in a compressed, two-and-a-half minute burst. It was simplicity as defiance.

Where many of his contemporaries were chasing the polished sounds of ’70s country-pop, Nelson’s approach here is intentionally stripped-down. The song’s massive success—it reached number one on the US Hot Country Songs chart and even crossed over to hit the Top 20 on the Billboard Hot 100—proved that authenticity, delivered with a smile and a train beat, could conquer the airwaves. It won him a Grammy for Best Country Song and became his indelible calling card, one of the few songs a non-country listener can reliably identify.

The Enduring Micro-Story of the Song

The true genius of this track lies in its ability to be both hyper-specific to the life of a traveling musician and universal to anyone who has ever found sanctuary in movement.

For me, the sound of that chugging rhythm is permanently tied to a memory: I was eighteen, driving a beat-up hand-me-down sedan across the vast, anonymous stretch of I-70 through Kansas, windows down, trying to make it to a friend’s college town before sunrise. The sense of isolation in the dark landscape was profound, but when this song came on the late-night radio, it was an instant injection of community. The simple, major-key melody and the assurance that “we’re the best of friends” transformed the lonely drive into a shared quest.

Another listener, perhaps a young coder working remotely from a different city every month, finds in the song’s lyrics a modern echo. The road is no longer a physical ribbon of asphalt, but a digital connection. The “friends that I just can’t wait to see” are now the collaborators and community built over video calls. The restless heart of the nomad hasn’t changed, only the mode of transport.

“The assurance that ‘we’re the best of friends’ transformed the lonely drive into a shared quest.”

And then there’s the simple act of putting on a pair of high-fidelity studio headphones to listen to the track. What becomes apparent is the meticulous placement of each element in the mix, the slight clank of the percussion, the distinct, almost woody tone of Trigger. It forces you to appreciate the craft behind the seeming effortlessness. This track is proof that sometimes the lightest touch is the most sophisticated. It feels like an anthem whispered in a smoky room, instantly recognizable and profoundly intimate all at once. Anyone who ever attempted to learn the simple, yet deceptively difficult, rhythmic figures on guitar lessons knows the challenge of capturing that loose-tight feel.

The song’s lyrical structure is incredibly economical. Nelson doesn’t waste a single word; every line contributes to the central theme of found family and perpetual motion. There is a sense of grateful fatalism here—this life is hard, but it’s our life, and we wouldn’t trade it for anything. The melodic loop is addictive, a perfect circular structure that mirrors the non-stop cycle of touring. You finish the song, and you instantly want to hit “play” and begin the journey all over again.

Willie Nelson created more than a successful single for a movie; he gave millions of people a two-minute, thirty-eight-second sonic home they could return to whenever the spirit of wanderlust called. It is one of the great American road songs, a piece of music that is as vital and road-worn as the man who wrote it on a little white bag. Give it a fresh spin, and let the rhythm carry you.

Listening Recommendations

- Jerry Reed – “East Bound and Down” (1977): Shares the kinetic, fast-moving energy and road-movie context of an essential soundtrack cut.

- The Allman Brothers Band – “Ramblin’ Man” (1973): Features the same celebratory, slightly outlaw-tinged theme of loving the wandering life.

- Johnny Cash – “I’ve Been Everywhere” (1996): An equally lean, travel-focused anthem, trading Nelson’s rhythmic chug for a list of endless destinations.

- Waylon Jennings – “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)” (1977): Captures the same mid-career sentiment of yearning for a simple, chosen life away from the system.

- The Proclaimers – “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)” (1988): A later, pop-adjacent track that maintains the relentless, forward-marching rhythm and optimistic tone of a journey.