The air in the listening room is thick, not with smoke, but with the phantom scent of high desert sage and a kind of palpable, cinematic dust. It’s an immersion that few pieces of music manage to conjure so completely. We are not just listening to a song; we are witnessing a closing scene, a final, desperate embrace in a wind-battered gorge somewhere near the Rio Grande. The song is “Seven Spanish Angels,” a track that, even forty years on, stands as an almost perfect distillation of country’s narrative grit tempered by the soaring, transcendent power of soul.

The story behind this single is one of those Nashville moments of pure, accidental alchemy. Written by Troy Seals and Eddie Setser, the song was a magnificent, violent ballad in the tradition of Marty Robbins’s Western epics. Willie Nelson, already a towering figure in the Outlaw Country movement, had the track on hold. However, producer Billy Sherrill, a man with an innate feel for the commercial crossover, heard the demo and knew it was exactly what Ray Charles needed for his 1984 country-focused album, Friendship.

Sherrill’s solution was the masterstroke: a duet.

The song was ultimately released in late 1984 as the lead single from Charles’s Friendship and was later included on Nelson’s 1985 compilation, Half Nelson. It was a smash, rocketing straight to the top of the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart—a remarkable feat that gave Ray Charles his only number-one hit on that chart. Its success was a powerful confirmation that the lines between country, soul, and gospel were less barriers and more highly charged conduits, ready to be bridged by artists of sufficient gravity.

A Study in Contrast: The Voices and the Verdict

To approach this song is to appreciate the brilliance of its vocal arrangement, a true study in stark, beautiful contrast. The narrative splits, with Charles taking the first verse, establishing the outlaw and his lover facing a grim end. Then, Willie Nelson steps in for the second verse, responding to the opening despair with a quiet, flinty resolve.

Ray Charles, as Brother Ray, brings the thunder and the tears. His voice is a force of nature, ragged and profound, steeped in the deep tradition of gospel. He sounds like a man already bargaining with the heavens, his delivery heavy with a mournful premonition. When he sings the chorus—*“There were seven Spanish angels / At the altar of the sun”—*it is pure, unvarnished catharsis. The way he shapes the melody, elongating and bending the notes, transforms a simple country phrase into a profound spiritual plea.

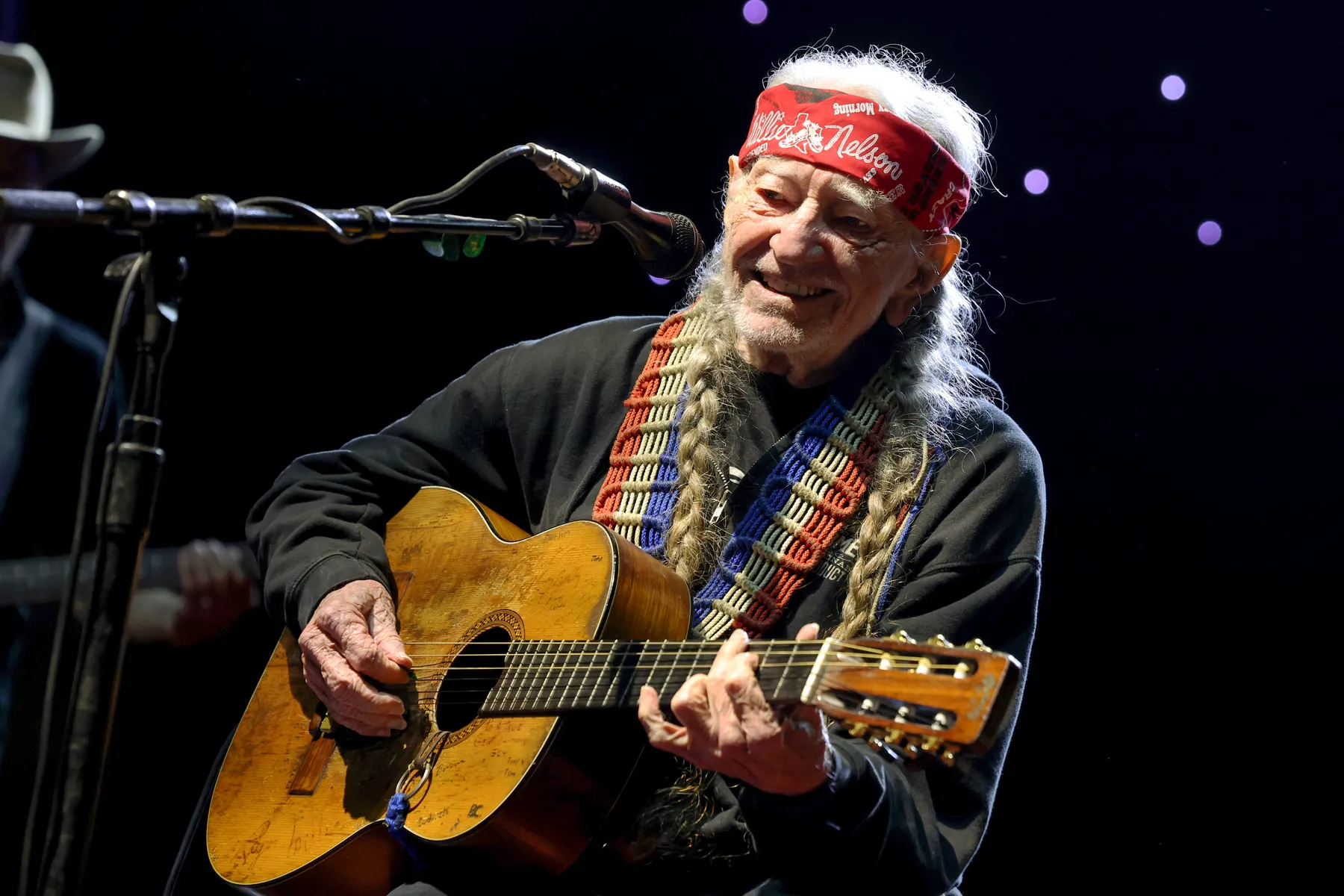

Willie’s turn is, characteristically, more restrained, his phrasing idiosyncratic and intimate. His voice, worn and supple, cuts through the arrangement like a piece of finely aged leather. There is a profound weariness in his tone, a sense of resignation that only a true road warrior could convey. While Ray Charles is reaching for the divine, Nelson sounds like he’s already made peace with the dust. It’s the difference between a preacher delivering a sermon and a friend offering a final, quiet truth. This dual perspective elevates the tragic romance from melodrama to myth.

The Sound of Desperation and Deliverance

The instrumentation, reportedly anchored by the veteran session players of the Nashville A-Team era, supports this drama without ever eclipsing it. Sherrill’s production is characteristically clean for the mid-eighties, yet it manages to retain a palpable sense of space.

The foundational rhythm section is understated, laying a solemn march that propels the story toward its inevitable conclusion. A mournful steel guitar cries softly in the background, weaving a lonesome counter-melody, its reverb tail long and haunting, simulating the vast, open country where this final stand occurs. The acoustic guitar, almost certainly Nelson’s iconic ‘Trigger,’ provides a raw, rhythmic pulse in the mix, a steady heartbeat against the encroaching silence.

But the arrangement’s core emotional driver is the subtle use of strings and, crucially, the piano. The piano is not flashy; it plays a simple, grounding role, offering warm, sustained chords that serve as a cushion beneath the rising vocal tension. As the narrative peaks, the string section swells—a classic country-politan touch—but here, it’s not schmaltz. It is the sound of the world’s sympathy pouring into the scene, emphasizing the ultimate sacrifice of the lovers.

The dynamics are key: the way the instruments pull back to allow Charles and Nelson’s alternating verses to dominate, then surge forward together for the shared, gospel-infused chorus, creates a breathtaking sense of build and release. It’s an arrangement that demands quality reproduction, one where the distinct timbres of the two legendary voices and the delicate echo of the strings can be fully appreciated. Finding a high-quality playback system is essential; this is a track that truly shines on premium audio equipment, revealing layers of texture that a simple car radio might miss.

Micro-Stories: The Enduring Echo

“Seven Spanish Angels” is a masterpiece of narrative economy. The song’s power lies not just in the vocal pairing, but in the universal truth it articulates: a love so total that one cannot live without the other. This theme of ultimate loyalty, even in the face of death, resonates profoundly.

I think of the song on a thousand late-night drives, the highway lights blurring into streaks of gold and red, listening on studio headphones to the stark clarity of Nelson’s voice as he promises they “won’t take me back alive.” It is a song for those moments of private, unshakeable resolution.

It’s also a track that reminds us how much we learn from the greats. For aspiring musicians, understanding the emotional weight carried by each word is more valuable than any textbook. The subtle genius in this performance is a masterclass in vocal delivery—far beyond what any piano lessons or vocal coach might teach.

“The greatest music is less about a style and more about a state of grace, a moment where two disparate traditions achieve a fleeting, perfect harmony.”

The piece closes not with a bang, but with a descent—the sound of the “thunder from the throne” and the seven angels praying for the lovers. The final notes hang suspended, fading away as the tragic duet resolves into a single, shared destiny. This is a song that belongs not just to country radio history, but to the broader canon of American musical storytelling. It is a quiet, devastating epic.

A great piece of music like this does not simply end; it settles into the memory, waiting for the next time the lights dim and the shadows lengthen, offering its somber, beautiful grace to another listener. It invites a final, meditative re-listen.

Listening Recommendations

- Marty Robbins – “El Paso” (1959): Shares the same core DNA: a cinematic Western narrative of a cowboy tragically doomed by his passionate love for a Mexican woman.

- Willie Nelson & Merle Haggard – “Pancho and Lefty” (1983): Another perfect outlaw ballad duet from the era, driven by a deep sense of loyalty and a lonesome fate.

- Ray Charles – “Crying Time” (1966): Showcases Charles’s seamless country crossover sensibility, blending his signature soul intensity with pedal steel guitar.

- Johnny Cash – “The Man Comes Around” (2002): A powerful, apocalyptic gospel-tinged narrative that shares “Angels'” themes of final judgment and spiritual resolution.

- Elvis Presley – “In the Ghetto” (1969): A dramatic, socially-aware story-song from the same era, built around a similar contrast between a tragic life and a promise of heaven.

- Patsy Cline – “Three Cigarettes in an Ashtray” (1961): A short, perfect example of the stark, emotional clarity that anchors the best country ballads.