There are crossroads in every long career. Moments when the artist steps out of the light they know and walks toward a sound that hasn’t fully formed yet—a risk, a reckoning, a necessary shedding of skin. For Willie Nelson, that moment arrived in 1973, not with a gentle fade, but with the sharp crack and barrel-smoke swagger of the Shotgun Willie album. This wasn’t just a new recording; it was a manifesto stapled to the door of Music Row.

The song “Shotgun Willie” itself, the title track, serves as the album’s mission statement. It’s a piece of music that feels less composed and more unearthed, a relic dragged from a dusty corner of a Texas honky-tonk and polished just enough to shine under the studio lights. Before this, Nelson had been the sublime songwriter behind hits like “Crazy” and “Hello Walls,” a respected Nashville commodity often constrained by the ‘countrypolitan’ expectations of his label, RCA. His contract expired, a move to the burgeoning bohemian music scene of Austin, Texas, had revitalized his spirit.

Then came the Atlantic Records deal, engineered by manager Neil Reshen and spearheaded by the legendary producer Jerry Wexler, with Arif Mardin doing the bulk of the production work in New York. Atlantic, a powerhouse of R&B and rock, gave Nelson what Nashville had denied him: control. The story, now legend, is that Willie wrote the titular song in a hotel bathroom, reportedly on a sanitary napkin wrapper, channeling a recent, real-life family confrontation involving firearms and a fast-moving car. The result is pure, unvarnished Texas myth.

The song opens not with an elaborate string arrangement, but with a driving, almost shambolic rhythm section. It’s built on a greasy, mid-tempo groove that swings with the loose-limbed ease of a late-night jam session. The drums, laid down by Paul English and Steve Mosley, are dry and immediate, lacking the distant echo of the slick Nashville studios.

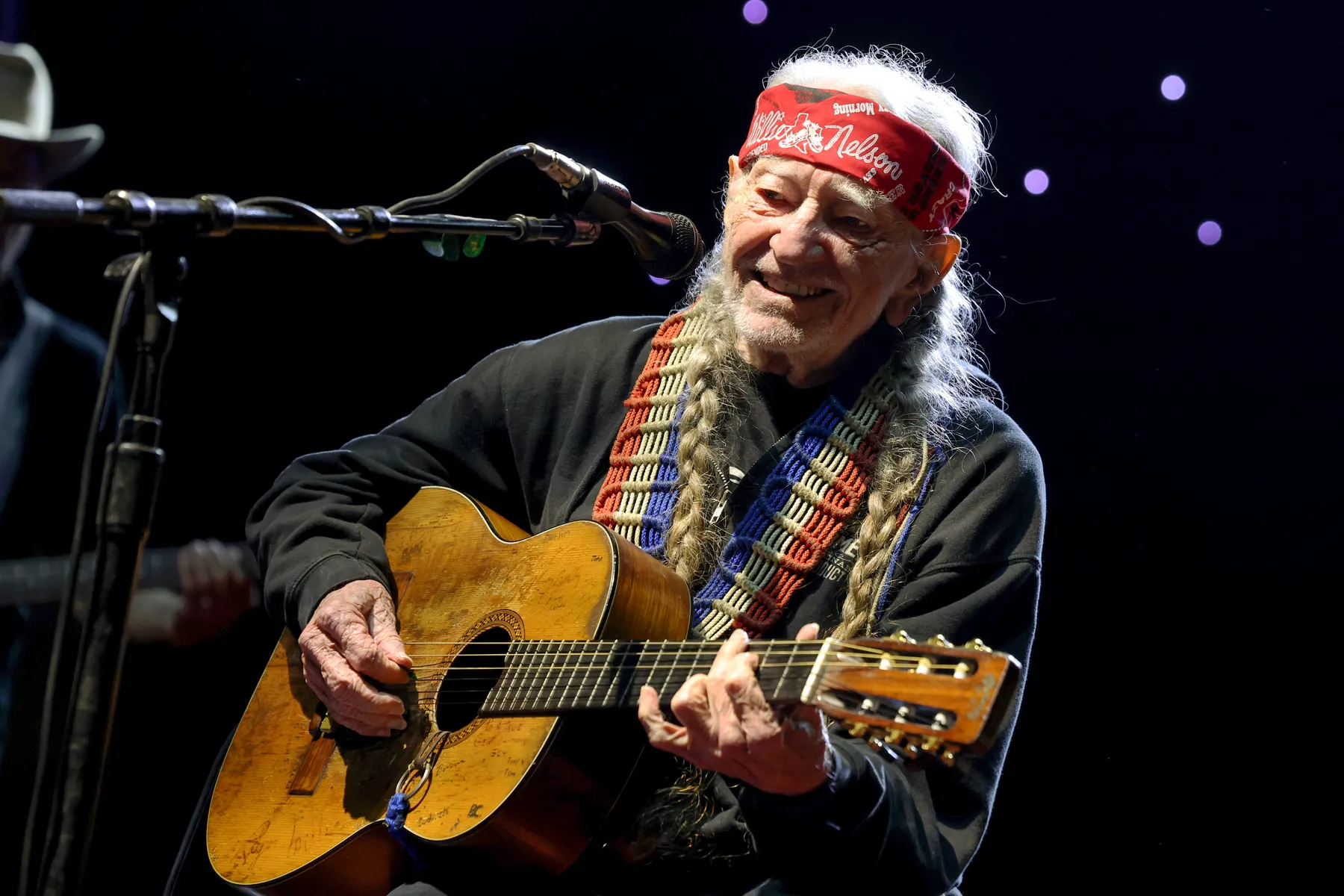

This raw texture is key to the song’s appeal. Willie’s own voice, already recognizable for its conversational phrasing and deliberate, almost lazy timing, is front and center. It sounds like he’s leaning in, sharing a secret or a wry joke. The acoustic guitar work is foundational, his famous nylon-string ‘Trigger’ providing the melodic backbone with those inimitable, clipped, jazz-inflected runs.

The piano, played by Willie’s sister, Bobbie Nelson, is essential, offering bright, honky-tonk punctuation that keeps the atmosphere light, even as the lyrics touch on hard times and self-preservation. It’s a contrast that defines this entire sound—a blend of serious musical chops and a casual, almost defiant attitude. The inclusion of the Memphis Horns—Andrew Love on tenor sax, Wayne Jackson on trumpet—might seem like a classic R&B touch, but here they are employed with restraint, adding a smoky, soulful swagger rather than an overwhelming brassy sweep. They are punctuation, not a headline.

The sound is not striving for perfection; it’s aiming for a palpable, lived-in feel. This shift defined the genesis of the “Outlaw Country” movement. It was the grit under the fingernails of a polished genre. It was Nelson declaring his right to exist outside the established commercial structures, to wear his long hair and beard on the album cover, and to record the songs he wanted, the way he wanted.

The lyrics are narrative gold, a short-form western cinema in verse. “Shotgun Willie / Lives in a boxcar / Got a lot of home audio equipment / And a broken heart.” The use of the past tense—”He used to have a home / But he lost it to the bank”—grounds the myth in relatable, contemporary American struggle, not just romantic cowboy fantasy. He’s an anti-hero who is deeply human, his problems mundane yet his reactions cinematic.

The song captures that unique Texas sensibility—the ability to be both world-weary and wildly free. It’s the soundtrack to a thousand road trips across state lines, the moment you realize the old rules don’t apply anymore.

“The Shotgun Willie persona is less about literal violence and more about a complete, unapologetic reclamation of self.”

Listen closely to the dynamics. The verse breathes, allowing space for the instruments to interact—the playful interplay between Willie’s voice, the bass walking a confident line, and Bobbie’s piano fills. Then, in the chorus, the arrangement subtly expands, the backing vocals entering to underline the hook, making it instantly infectious. For a song recorded in 1973, the mix feels surprisingly modern in its clarity and separation; this is thanks to the world-class ear of Arif Mardin. The clarity is such that someone learning the arrangement might easily transcribe the part for their next round of guitar lessons.

This particular piece of music, while only a minor hit on the country charts, was a cultural earthquake. It didn’t chase the trends; it set them. It opened the door for Red Headed Stranger a few years later and cemented Nelson’s status as a legend who refused to be contained by a three-minute, radio-friendly formula. He proved that authenticity and the freedom to mix genres—country, blues, jazz, and rock—could ultimately lead to greater, more enduring success. This era marked a crucial inflection point, transitioning Willie from Nashville’s highly regarded staff songwriter to an American icon and the ultimate bandleader of his own destiny. The story of Shotgun Willie is the story of artistic liberation, proving that sometimes, you have to break things—or at least shoot at a car—to truly find your sound.

Listening Recommendations

- Waylon Jennings – “Lonesome, On’ry and Mean” (1973): Similar outlaw manifesto energy from the same era; pure grit and defiance.

- Doug Sahm – “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone” (1973): Shares the loose, genre-bending Texan sensibility present on Shotgun Willie.

- Jerry Jeff Walker – “Gettin’ By” (1975): Captures the rambling, nomadic spirit and casual complexity of the Texas singer-songwriter scene.

- Kris Kristofferson – “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33” (1971): A classic portrait of the weary, poetic drifter, matching Willie’s introspective side.

- Billy Joe Shaver – “Georgia on a Fast Train” (1973): Rough-edged, autobiographical storytelling with an identical release-year rebellious streak.

- The Rolling Stones – “Happy” (1972): For the stripped-down, soulful rock-and-roll swagger that the horns give “Shotgun Willie.”