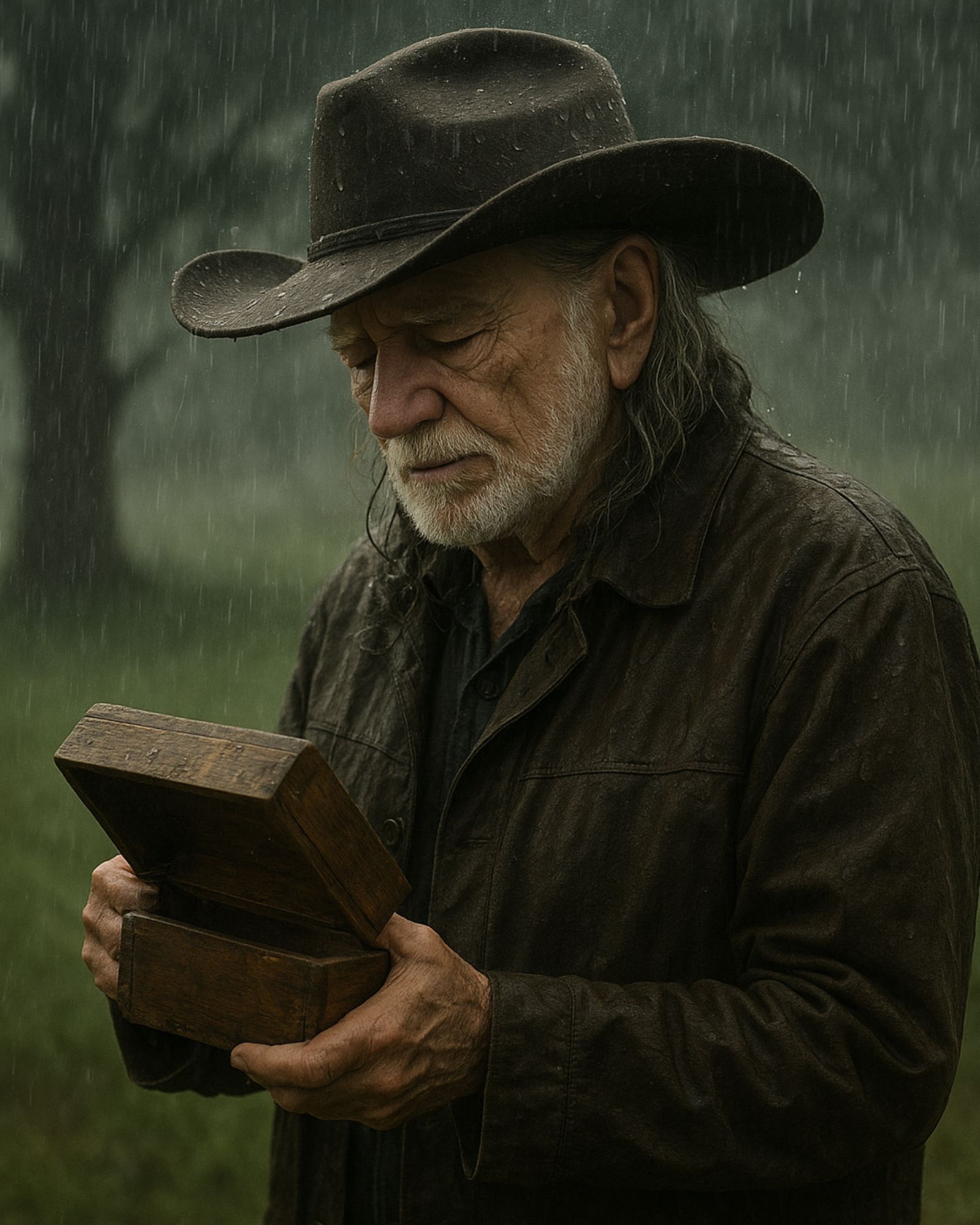

At 91, Willie Nelson stunned the world when he revealed a secret on a rainy night in Texas. People thought that at his age, he would only be wandering with his old guitar, but no… Beneath the roots of an old oak tree on his ranch, he discovered a wooden box that had been forgotten for decades. Inside were not only yellowed letters, but also a handwritten song no one had ever heard. Willie softly said: ‘Some songs aren’t meant for the stage… but maybe it’s time the world hears this one.’ What moved fans most was… that hidden song seemed to echo one of his most timeless classics. And, surprisingly…

I first heard Willie Nelson’s “Always on My Mind” the way many people do: alone, after midnight, when the world is too quiet to keep your thoughts in order. The radio dial felt loose under my fingers. A hush, then the soft bloom of strings, and his voice arrived like a late apology—deliberate, unhurried, almost conversational. You can talk about history and charts and all the accolades this song collected, but its power lands in that first phrase. It’s the sound of someone deciding to tell the truth, not because it will fix anything, but because the truth deserves its own moment.

Released in 1982 on Columbia Records, “Always on My Mind” is the anchor and namesake of the album that reintroduced Willie Nelson to a broader audience beyond the outlaw-country halo. He had already made his mark—long before, he’d been the songwriter whose words other artists took to the bank; then he became the artist who steered his own myth. By the early ’80s, he was a household name. But this track, produced by Chips Moman, caught him in a different posture: less renegade, more confessor. He set aside the wink and the grin for a kind of radical sincerity.

The composition wasn’t new. It was written by Wayne Carson, Johnny Christopher, and Mark James, and it had lived an earlier life through other voices—most famously recorded in the early 1970s by Elvis Presley. Nelson’s reading doesn’t compete with those earlier versions; it sidesteps them. Where Presley sounded like a man wrestling himself, Nelson sounds like someone who has already lost the argument and is guiding you carefully through the remains.

The arrangement is simple but meticulously shaped. A small rhythm section keeps time with a slow heartbeat. The strings are almost vapor—their entrances feel like breath on a windowpane, here and gone. There’s a ghost of organ, a discreet line that lifts the harmonic floor without calling attention to itself. You can hear the room, too. The reverb tail off Nelson’s vocal is short and warm, enough to suggest space without bathing him in sentimentality. It’s the right setting for a voice that refuses drama even as it carries it.

Take the opening verse. Nelson sits right on top of the lyric, neither rushing nor lagging. His timbre has that familiar grain—sagebrush and cedar, a bit of smoke. He stretches the ends of phrases just enough to sound like he’s weighing each word before he lets it fall. The vowels are rounded; the consonants tap gently like knuckles on a door. The vibrato arrives late, almost an afterthought, and then is gone. The phrasing is conversational, but the intensity is theater-level. The result is a performance that feels like testimony.

Listen for the “attack and release” logic of the strings. They swell in anticipation of the chorus and then retreat, a tide that knows when to come in and when to let the sand show. The “sustain” in the piano chords—yes, there’s a piano tucked in there, comping with priestly restraint—holds just long enough to keep the harmony alive between lines. The acoustic guitar shades the edges, its strum dry and steady, like the rustle of a jacket in the backseat. This is a piece of music that believes in restraint, in the durability of small gestures.

What makes Nelson’s interpretation so durable is the narrative implied by the sound. He isn’t begging for forgiveness; he’s cataloging a failure with tenderness. The lyric is full of conditional promises, regret framed as inventory. Behind it, the band plays like people who grew up on jukeboxes and church choirs—economical, attentive, allergic to clutter. The rhythm section never makes a fuss; they just carry the confession across the room.

In career terms, this cut sits at a hinge. Nelson’s ’70s output gave him authority; the early ’80s turned that authority into reach. The “Always on My Mind” album arrived as the radio landscape was shifting, with pop-polish creeping into every genre. Nelson doesn’t chase polish here; he lets the song wear a clean shirt and good manners, then trusts his voice to do the talking. Columbia knew what they had. The single moved quickly and broadly—on country stations first, and then onto playlists that didn’t always make space for him. It helped continue a stretch where Nelson could cross over without cutting away his roots.

The producer’s touch matters. Chips Moman had made records that understood how to get out of a singer’s way. On this track, the balances feel hand-carved. The strings never bully the vocal; the rhythm never buckles under syrup. The mix is intimate, with a center channel that could be mistaken for someone speaking from across a kitchen table. If you listen on good studio headphones, you hear little bits of humanity: a lip smack, a breath hitch, fingers adjusting on a fret. These are the things modern smoothing often sands down. Here, they’re left like woodgrain.

There’s a common temptation to call the song “simple.” It isn’t. Harmony does quiet, complicated work. The chorus pivots through changes that give the melody a place to lean. Those passing chords paint the apology as something lived-in and layered. The melody itself travels a modest distance, but the emotional geography is wide: resignation, memory, a hint of plea, and then that closing drop into acceptance. This is songwriting with few moving parts and a lot of leverage.

I keep thinking about the microphone picture. In my mind’s eye, Nelson stands a step off-axis, head tilted, eyes level with a lyric sheet he barely needs. The take isn’t about maximum power; it’s about the right temperature. The engineer brings the fader up until the voice overtakes the noise floor and sits like a lamp on a nightstand. What happens next is a kind of trust exercise between singer and silence.

Here’s a small, modern vignette: a woman in a rideshare, late shift over, city orange outside the window. She scrolls past news and noise and lands on a playlist of old ballads. When Nelson’s voice enters, she doesn’t change lanes; she changes posture. The line “maybe I didn’t love you” arrives not as a quote, but as a question she’s been asking herself. The car keeps moving, but for those three minutes, she sits perfectly still.

Another scene: a father packing boxes after a long marriage. He finds the “Always on My Mind” album in a stack of vinyl and sets it on an old belt-drive turntable he hasn’t used in years. The needle drops, there’s a small burst of dust, and then the room re-learns its echoes. He doesn’t cry. He takes inventory along with the song: what he said, what he didn’t, what he might still have time to do for other people he loves. He replaces the sleeve carefully, as if the motion could put other things back where they belong.

Third scene: a young musician learning the song’s changes in a living room, phone propped up to capture a run-through. They keep the tempo slower than the records they know. Their thumb brushes the strings, their foot keeps time on a rug. When they finally sing the first line, it sounds less like imitation and more like discovery. The lesson isn’t how to embellish; it’s how to hold back.

“Restraint, lovingly applied, can feel like the loudest kind of honesty.”

That’s what Nelson finds here. His vocal isn’t empty of ornament; it simply refuses to hide inside ornament. You’ll notice the way he approaches the ends of lines—sometimes straight, sometimes with a small, cracked flourish that isn’t quite a sob and isn’t quite a yodel. The signature nylon-string guitar tone—his weathered companion—flickers through with the authority of an old friend who knows when to speak and when to listen. Even if you’ve never picked up a guitar, you understand the eloquence of those brief phrases.

No review of this track would be complete without acknowledging how fully it entered the culture. Awards followed; radio kept it in heavy rotation; many sources note it topped country charts and made meaningful inroads on pop playlists at a time when crossover wasn’t guaranteed. But numbers tell a colder story than the one you hear. What you hear is the human capacity to see the harm and still choose tenderness. It’s not absolution. It’s a record of care.

The timbral palette also merits a closer listen. Strings, yes—but these aren’t the thick beds you hear on syrupy ballads. They rack in from the sides, whisper on cue, and then back away, leaving air around the voice. The piano is voiced like a confidant, no bright hammer clatter, more felt than wood. The bass is upright in spirit even if it’s electric in fact; it moves with a slow, careful dignity, like someone walking while carrying a sleeping child.

I’m struck by how the recording resists chronology. It’s rooted in a certain era, yet it doesn’t sound mothballed. Part of that is Nelson’s timeproof instrument: a voice that ages like a well-used leather chair. Part of it is the text. Apology ages better than swagger. You can slip the track into a contemporary playlist and nothing breaks. The mastering isn’t brash; the dynamic range hasn’t been ironed into a gray rectangle. On a decent home audio setup you can hear the softest details without losing the weight of the chorus.

There’s also the question of lineage. The song’s earlier life with Presley matters because it underlines how interpretation changes meaning. Presley sounded cornered. Nelson sounds free enough to be honest. The text is the same, but the character study is different. That’s the magic of durable songwriting: the map remains; the traveler changes.

If you’re a player, the track is an exercise in economy. The rhythm guitarist learns to place chords like furniture—everything where it belongs, nothing blocking a doorway. The pianist learns to value the sustain pedal as a painterly tool. The drummer learns that the subtlest brush on a snare can be as decisive as a crash. For readers who dabble in arrangements, the string charts are a masterclass in what not to write, leaving space for emotion to reverberate. For those more visually inclined, imagine how the arrangement would look on a sparse lead sheet: staves with generous margins, dynamics written in lowercase.

There’s an alternate universe where Nelson turns up the twang and turns this into a barroom singalong. Thankfully, that isn’t this world. He holds the center. He lets the song be small. Every so often, a modern cover comes along and adds tricks: modulations, big finales, theatrical pauses. Nelson’s version comes closest to prayer.

I should say plainly: you don’t need to have failed someone to feel the weight of this record. You only need to have lived long enough to know that love and attention are not the same thing, and that attention often follows love too late. That is why the track keeps being discovered by listeners who weren’t alive in 1982. Its ethical center is portable.

A practical aside, since so many readers ask how best to listen: don’t rush it. Let the first verse come to you. If you’re the type who likes to mark up scores, the song rewards a look at the chordal movement—how the harmony mirrors the lyric’s second thoughts and returns. For those inclined to accompany themselves, this is a gentle way to test touch; even beginners can find a route through the voicings without needing formal piano lessons. If you do go hunting for sheet music, find an edition that preserves the song’s long arcs and doesn’t cram the page with unnecessary decorations.

As for the larger legacy, “Always on My Mind” may be the most moving reminder that Nelson’s interpretive instincts are as essential to his canon as his songwriting. The album delivered other pleasures, but this track stands as a consummate argument for minimalism in country balladry. Not minimalist as in barren, but minimalist as in just enough: enough harmonic interest, enough orchestral color, enough beat to keep the heart moving and the mind awake.

The glamour is there—the sheen of strings, a studio glow—but so is the grit of human breath and steel. That contrast gives the song its bite. It’s like a polished stone you can still feel the river on.

In the end, the song doesn’t ask you to forgive its narrator. It asks you to witness him. That’s why it endures. Consider this your invitation to hear it again, not for nostalgia’s sake, but to measure the distance between who you were when you first heard it and who you are now.

Listening Recommendations

— Elvis Presley — “Always on My Mind”: The 1972 reading leans more dramatic, revealing how interpretation reshapes the same melody.

— Patsy Cline — “Crazy”: Another Nelson-connected ballad where elegant phrasing and classic Nashville restraint turn regret into poetry.

— Kris Kristofferson — “Help Me Make It Through the Night”: Late-night candor with spare accompaniment and a voice that chooses truth over polish.

— Ray Price — “For the Good Times”: Lush strings and an adult, unhurried goodbye that shares this song’s dignified melancholy.

— Johnny Cash — “Hurt”: A modern standard of confessional economy, using silence and gravel to devastating effect.

— Emmylou Harris — “If I Needed You”: A hushed, harmonious plea with acoustic grace that pairs well with Nelson’s soft-focus sincerity.