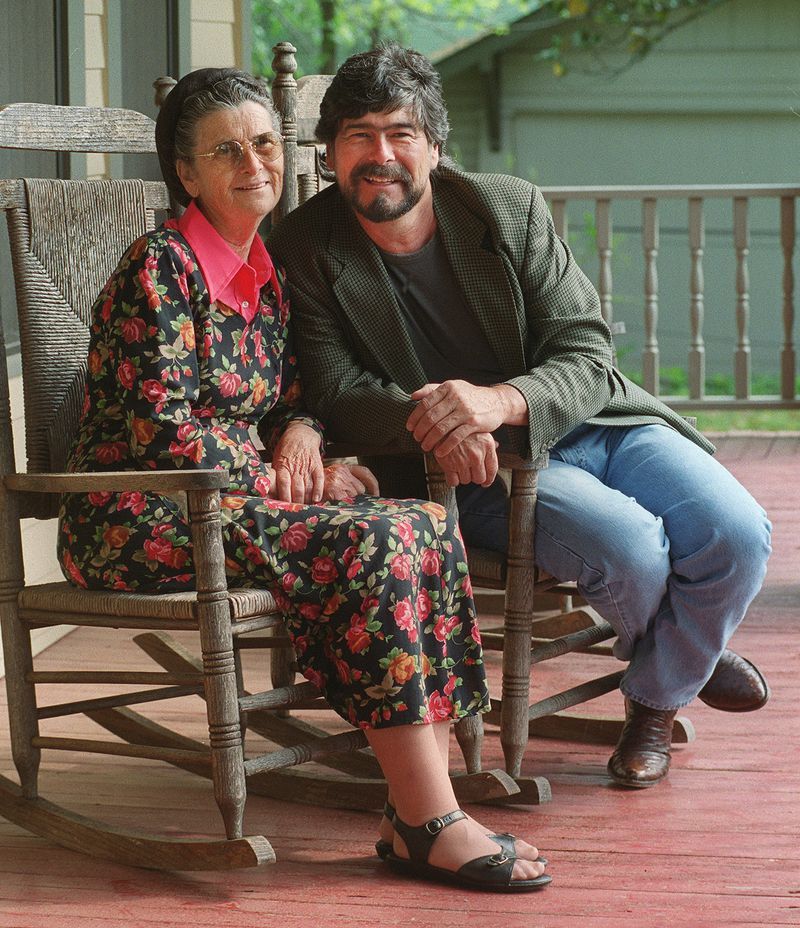

“She taught me more than how to sing… She taught me how to mean it.” For Randy Owen, the most important lessons didn’t come from Nashville, but from his mother in a small Fort Payne kitchen. She was the one who quietly taught him that “songs were meant to be felt before they were sung,” a truth he carried onto every stage for decades. Even now at 74, when the lights go down, he says he can still feel her standing right there beside him, her gentle voice the true heart behind the music.

I remember the first time I heard “Lady Down on Love” through the warm murmur of late-night radio: a hush of room tone, a voice recorded close to the mic, and the kind of string bed that suggests it’s going to tell you something you’ve been avoiding. Before the chorus ever arrives, you can feel the floorboards of a life shifting—one verse at a time.

Randy Owen is best known as the lead voice of Alabama, and though we often speak of this track as a band classic, its authorship matters. He wrote it himself, and his signature is everywhere—the plainspoken empathy, the split-screen narrative, the unhurried melody that lets memory sit where it hurts most. Released in 1983 as the third single from Alabama’s chart-ascendant The Closer You Get…, it became a No. 1 country hit and a pillar of the group’s run in the early ‘80s. The album was produced by Alabama with Harold Shedd for RCA Nashville, a partnership that helped define their country-pop blend. Wikipedia+2Wikipedia+2

On paper, “Lady Down on Love” is a straightforward ballad; in the ear, it’s a soft-focus film. The track opens with gliding keyboards that feel like light across a polished floor, drums that breathe rather than bark, and a restrained electric shimmer tucked around the vocal. You hear the band’s country roots—clean picking, a rhythmic pulse hospitable to two-step sway—but you also hear the crossover polish that marked Alabama’s 1983 moment. That polish wasn’t accidental; The Closer You Get… leaned into pop-friendly textures and arranged strings with care, aligning the band with radio’s expanding palette. Wikipedia

Listen closely to the mix and you’ll notice how the arrangement keeps making room for the story. There’s a careful dance between what’s stated and what’s withheld. The bass sits supportive, not showy. The snare is cushioned, almost upholstered. When the strings rise, they don’t rush the sentiment—they underline the sentences you can’t say out loud. This is a piece of music that understands how dynamic control can make emotional candor feel safe.

Owen’s vocal is the center of gravity. He sings with a forward placement—clear, slightly nasal on the attack but rounded on the release—so that every consonant lands without scraping. He leans into the long vowels at the ends of lines, giving the words just enough reverb tail to feel like they’re answering themselves. This is not the crying-in-your-beer school of country melodrama. It’s steadier than that, more observational. The ache is stitched into the phrasing.

The writing splits the narrative into two vantage points: first the woman, then the man. In verse one, she is out among friends after a divorce, but she isn’t free so much as unmoored. Verse two turns the camera around; the husband admits the distance, the absence, the betrayal. Two lives, two truths, and one thread: the recognition that time went by while their marriage quietly redefined itself into something it was never meant to be. Contemporary accounts have long highlighted that two-perspective structure—rare in mainstream country at the time—and note that Owen drew inspiration after seeing a group of women out celebrating a friend’s divorce, the friend herself markedly uncelebratory. Wikipedia

What gives the song its staying power is the humility of its storytelling. Nobody is redeemed here for the price of a bridge; nobody wins the scene. The chorus admits what both characters already know—that freedom is a complicated word when what you wanted all along was reliability, ordinary tenderness, a life with fewer caveats. The melody resolves without triumph. It simply arrives, like evening.

At the level of color and texture, the track is a primer in early-’80s Nashville craftsmanship. Keyboards do much of the glue work; you can imagine a Yamaha or a Rhodes-style timbre laid in velvet layers, a sound common to the era’s crossover productions. Session strings—Nashville’s own contingent, arranged with an ear for contour rather than bombast—lend a gentle arc. This aligns with the personnel and approach that The Closer You Get… is known for, in which strings and keyboards were used to broaden the band’s palette while preserving its roots instrumentation. Wikipedia

Two small choices make a big difference. First, the guitars don’t press. There’s tasteful electric filigree and likely some acoustic strum locking with the rhythm, but tone and placement keep them conversational—supporting, never crowding. Second, the drums feel mixed for breath, not impact. That gives space for the low-mid warmth of the vocal and the pads to bloom, which is why the song plays just as well in a quiet room at 1 a.m. as it does on a highway with the windows down.

It’s also worth situating this within Alabama’s career arc. By 1983, the band had transformed from bar-hardened road warriors to a juggernaut of country radio. The Closer You Get… followed the success of Mountain Music, and together these records represent a shift toward broader pop appeal without abandoning narrative sincerity. “Lady Down on Love” is essential to that shift, a statement that ballads could carry the same commercial weight as barn-burners. The record’s chart performance confirmed the bet: it kept Alabama’s No. 1 streak intact, while the album itself became one of their most successful. Wikipedia+1

I think of three small listening scenes that reveal the song’s quiet force.

A woman in her thirties, returning from signing final papers, pulls into an empty grocery store lot and doesn’t turn the car off. She lets the song fill the interior like a conversation she doesn’t have to have with anyone else. The first verse names her fear without using her name. It gives her permission to feel tired rather than triumphant.

A man in his forties, overworking to outrun what he won’t say at home, finds himself alone with the second verse. The lyric does not forgive him. It does something more difficult: it sees him as a person who made a choice and now has to live in the shape of that choice. The melody doesn’t console; it witnesses.

A late-night DJ, years into a small-market career, threads “Lady Down on Love” between a request and an advertisement. In the glow of the board, the song’s steadiness becomes a kind of duty of care. Not every listener is in crisis. But enough are. The track offers them a soft place to land that still feels honest.

“‘Lady Down on Love’ is what happens when a song refuses melodrama and chooses plain speech—sorrow that stands upright.”

As a performance, it’s also a study in balance. The band’s rhythm section supplies quiet ballast; the strings lift but do not sentimentalize; the keyboard pads lend a dusky sheen that keeps the mix contemporary for its day. If you listen on quality studio headphones, you’ll notice how the vocal sits exactly where it needs to—forward but never overbright—an engineering choice that preserves intimacy without losing clarity.

Much has been made of how Alabama blended country storytelling with pop architecture in this era. The Closer You Get… is the clearest example, and “Lady Down on Love” sits near the emotional center of that statement. Track lists and credits from the period show the group co-producing alongside Harold Shedd, a pairing that consistently found a usable middle ground between twang and polish. Wikipedia

There’s one more reason the song lingers: it respects the listener’s intelligence. We are not told every detail of the couple’s history, though enough is outlined to make their trajectory legible. The verses compress decades into a few stark disclosures. The chorus, instead of delivering a cathartic blast, offers recognition. You can trace a line from this to later country ballads that foreground perspective-taking over pyrotechnics.

A note on instruments you can watch for on a focused play: the guitar often functions as a gentle counter-narrator, sketching replies under the vocal line, while a simple piano figure adds a domestic hue—like light spilling from a kitchen at midnight. None of it calls attention to itself. That modesty is precisely the point.

From a listener’s standpoint today, the record still benefits from mastering that favors warmth over brittle top end. If you’re used to modern loudness wars, the track can feel quieter at first; turn it up and the air around the instruments emerges. That air is where the song breathes. For those who play or teach, the chord movement is approachable without being simplistic—something you sense when you search for the tune’s sheet music and realize how elegantly its progressions serve the lyric.

Historically, 1983 was a hinge year. Country radio was receptive to crossover gestures, and Alabama was among the acts that proved how far you could go without losing narrative spine. By releasing “Lady Down on Love” as a single late in the album cycle, the band telegraphed confidence in their balladry—and the market answered accordingly, with the song ascending to the top of the country charts that fall. Wikipedia+1

What I admire most is the dignity the song extends to both protagonists. It acknowledges the ways we disappoint each other without collapsing into moral theater. In that sense, it still speaks to the present. We are a culture overfamiliar with public reckonings and underfamiliar with private accountability. The record suggests an alternative: name the thing plainly; live with what you’ve named; keep walking.

If you come to “Lady Down on Love” for vocal heroics, you’ll find precision instead. If you’re here for a grand orchestral sweep, you’ll hear restraint—enough string glow to widen the frame, not enough to blur the faces in it. If you want a roadmap out of heartbreak, the song hands you a mirror. And maybe that is the last, best insight it offers: some endings are not failures so much as faithfully drawn conclusions.

Alabama’s success in this period was a compound of radio sense, road seasoning, and the clarity of Randy Owen’s pen. This ballad showcases all three. And while it’s indelibly an Alabama track from The Closer You Get…—with the band and Harold Shedd guiding the shape—it also feels personal, as if Owen is handing you a thought he wrote down for safekeeping years ago. Wikipedia

Return to it with attention. Let the strings come in like a weather change. Listen for the little held notes on vowels, the way the drums exhale, the way the harmony tucks under the lead in the chorus. It is the sound of two people telling the truth in different rooms.

In the end, “Lady Down on Love” reminds us that adulthood is often a study in unglamorous courage. You take stock, you admit what didn’t work, you try to be kinder next time. The record doesn’t promise new love or tidy closure. It offers something rarer: respect for complexity, honestly sung.