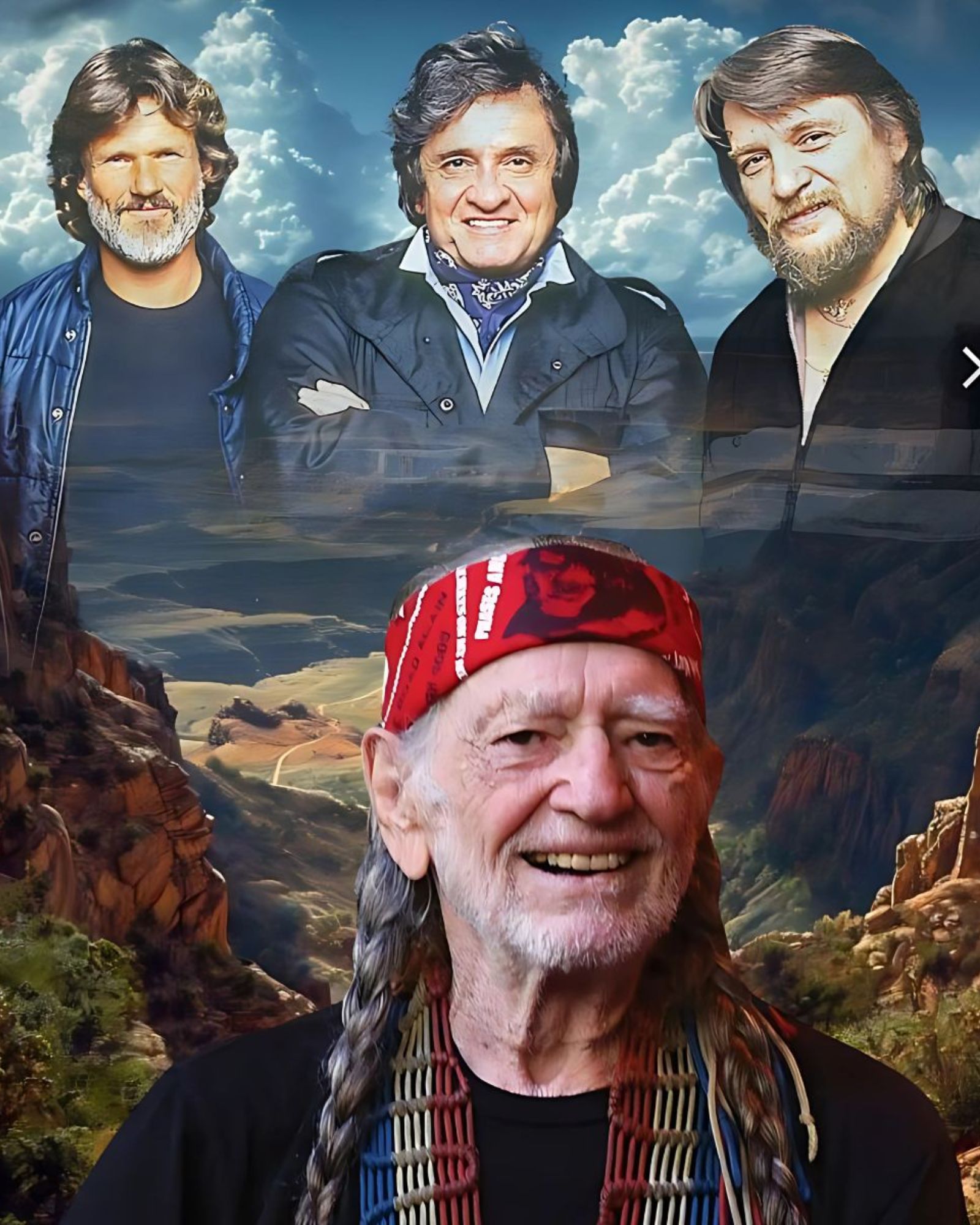

Some songs don’t just get sung — they reincarnate, carrying pieces of every life they’ve touched. ✨ “Highwayman” is one of those rare songs. Brought to life by the legendary supergroup — Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson — it unfolds as a ballad told through four voices, each one a chapter in the eternal journey of a restless spirit. With every verse, a new life emerges — a drifter, a sailor, a dam builder, a star-wanderer — yet all tied together by the same undying soul. What few realize is that Jimmy Webb wrote it not just as a song, but as a meditation on reincarnation, on how existence itself refuses to end. It’s more than music — it’s a testament to resilience, to loss, to the eternal return of the human spirit. No matter where the road leads, a part of us always finds its way back.

The house lights fall to ember and the first cheer moves like a gust across the Nassau Coliseum. A familiar shuffle settles into the room: a train rhythm dressed as country, steady as a mile marker. Four silhouettes step into the same cone of light. Willie Nelson plants himself at the mic with that sly half-smile; Johnny Cash stands just off his shoulder, all gravity and black; Waylon Jennings leans into his guitar as if it’s the fifth member; and Kris Kristofferson watches like a songwriter seeing his words come back to life—even though this time the words belong to another great American writer, Steve Goodman.

This version of “City of New Orleans” arrives to us as part of Live – American Outlaws, the 2016 box set that finally put the March 1990 Nassau Coliseum show on the record, a full portrait of the supergroup at touring peak. The set documents the quartet at a moment when their collective legend was already etched in granite, yet the performances still spark with the looseness of musicians who trust each other enough to leave room for surprise. The specific date and venue—Uniondale, New York, March 1990—matter here; it’s the north-end echo of a Southern story, and the crowd leans in to meet it halfway. Johnny Cash Official Site+1

“City of New Orleans” is a song with a winding map of its own. Written by Steve Goodman and first recorded for his 1971 debut, it became a hit for Arlo Guthrie in 1972 and later climbed to the top of the country charts in Willie Nelson’s 1984 version—a rendition that also brought Goodman a posthumous Grammy for Best Country Song. In other words, by the time The Highwaymen sang it together in 1990, the track had already lived several lives, each one carving a new groove into the American ear. Wikipedia+1

What makes this live take stand out is the way the quartet balances authorship and fellowship. Willie takes the opening lead—his phrasing as unhurried as a late train that no one dares rush. The attack on his acoustic guitar is light, airy; the sustain vanishes as quickly as it appears, leaving space for a responsive electric part to curl around the vocal lines. Cash doesn’t crowd; he waits, then drops a baritone harmony that functions like a guardrail. You can hear Waylon’s right hand telegraphing the groove, those clipped, confident strokes that give the band a backbone without hardening it. Kristofferson enters like a good narrator—low in the blend at first, then lifted by the chorus.

In a lot of live country from this period, you get precision; here, you get precision that breathes. The drummer rides the hi-hat as if marking telephone poles—tick-tick-tick—while the bass keeps its notes short enough that the kick can speak. When keys slide in, it’s a soft bed more felt than noticed, a texture that reads like piano even when it might be an electric patch. The reverb tail on the vocals is short, almost a club-style setting for an arena show, keeping the words present and conversational, closer to storytelling than spectacle. That decision—whether by front-of-house instinct or post-production taste—shapes the entire performance: you feel near them.

Because the camera and microphones (and later the mastering) keep the room at a polite distance, the song becomes a traveling companion rather than a broadcast. You can hear the audience as a cushion rather than a roar—thousands of lungs breathing with the tempo. The band plays into that intimacy. There are no grand codas or gratuitous modulations. It’s a road-burnished reading of a piece of music that never needed extra polish, only care.

There’s an unspoken drama in how The Highwaymen divide the verses. Willie’s tone tilts toward gentle witness; when Cash takes a line, gravity enters the car; Waylon brings the highway—dust, diesel, horizon; Kris shades the narrative with the memory of the writer’s room. None of them strains for ownership. If you close your eyes, the song becomes a passing landscape seen from four different seats in the same coach. The harmonic blend is warm, never syrupy. Listen for the little moments: Cash’s slight aspirate before a downbeat, Waylon clipping a fill to make room for Willie’s breath, Kris smiling through a phrase you can almost hear him remember.

As a concert document, this performance also speaks to the group’s place in 1990. The outlaw era had already done its history-making; Nashville’s mainstream was changing; and the quartet’s union had turned from experiment to institution. Yet on “City of New Orleans,” the institution re-discovers the impulse. The song is a travelogue, yes, but it’s also a ledger of American passages—work and rest, strangers and kin, loss and persistence. The Highwaymen understand that and don’t spell it out. They let tempo, timbre, and time handle the sermon.

I’m struck by the rhythm section’s restraint. The drummer is a master of implication; he hints at a train beat without painting it in neon. The bass player sits right on the kick—no showboating, no extra slides—just the patient footfall of wheels eating track. Waylon’s electric isn’t overdriven; it’s chewy around the edges, with a touch of spring reverb that blooms and closes like a door catching on its latch. Willie’s acoustic provides the filigree, a lattice of little upstrokes that keep air in the arrangement. When the chorus comes, the three-part blend swells just enough to lift the roofline, then returns to the verse like a traveler finding his seat after checking the platform.

“City of New Orleans” sits near the midpoint of the Nassau set, a calm eddy in a show that otherwise swings between barnburners and signature statements. On the same night you get “Highwayman,” “Ring of Fire,” and “Folsom Prison Blues,” all delivered with the elbow-out confidence of men who know exactly what those songs mean to people. This track, by contrast, is an invitation rather than a declaration. It asks you to ride along. If the big hits tell you who these artists became, this one reminds you how they listen—to each other, and to the country they’re still crossing. Johnny Cash Official Site+1

The voice leading is another quiet joy. Cash’s harmonies sit below the melody like ballast; Kristofferson drifts above, thin and earnest; Waylon threads the midline. The blend is imperfect in the best way, human and hand-made. On a technical level, the band could have thickened the chorus with more singers, added a pad, or pushed the preamp to get more sheen. They don’t. The human blend wins because it tells the truth: good friends sing a song they love. In an era before pitch correction became a reflex, that choice reads as generosity.

The narrative motion of Goodman’s lyric—stations, names, faces—pushes the band forward without forcing them to rush. Willie phrases with soft syncopations, sometimes landing a half-hair behind the beat, sometimes sliding across it. If you’re listening on studio headphones, you can catch the small in-breaths that set up those entries, the kind of detail that turns performance into felt presence. The tempo never wobbles; the pocket is so locked that even subtle pushes feel like conversation rather than correction. YouTube

One of the enduring pleasures here is hearing a crowd in a sports arena respond to a folk-country travel ballad with patience. No one is waiting for the big drum fill. They want the picture. Out of all the classic songs the quartet could play, they choose one that honors the American habit of getting from one place to another—by rail, by road, by memory. It fits the group because The Highwaymen themselves were a moving republic, four citizens of the song crossing state lines together. The Nassau mix captures that paradox: the glamor of the arena and the grit of a band pretending it’s in a bar.

There’s also a lineage at play. When Willie sang “City of New Orleans” in 1984, he turned Goodman’s lament into a celebration and took it to the top of the country charts. Six years later, surrounded by friends, he recasts it again—not a chart bid, but a nod to a writer he admired and a tune that had already proved its resilience. You can feel that respect in the tempo choices, the unsentimental delivery, the refusal to milk the pathos. It’s the maturity of players who know that each verse lands best when you don’t push it. Wikipedia

The instrumentation stays lean, a reminder that complexity is a choice, not a requirement. The keys color the edges, a faint halo that keeps the vocals warm. Rhythm guitar and bass do the heavy lifting; the lead slips in filigree phrases, sometimes echoing the melody, sometimes answering it. If there’s a brief ride-out, it’s tasteful and small, just enough to suggest tracks disappearing into the night. Somewhere in that blend, you’ll also catch a hint of piano during the transitions—small chords that function like station announcements, nudging us to the next stop. The ensemble manages dynamics through subtraction rather than volume, an old road band’s trick.

“Four voices, one track, and the quiet conviction that a song doesn’t need fireworks to light up a room.”

It’s worth placing this performance within the broader arc of the group’s career. The Highwaymen formed in the mid-’80s as a collaboration among equals, each man a star with an established catalog. By 1990, they’d logged the miles to become more than a novelty; they were a working band with a shared book of songs and an audience that cut across generations. The American Outlaws release lets us hear that chemistry finally put to tape as a complete night, not just scattered TV appearances or rumor. The curation in the box set is careful without being fussy, and the Nassau tracks—including this one—sound newly alive, not embalmed. Discogs

On the listening side, the recording rewards good speakers. The low end is tidy, the vocal images are centered and stable, and the cymbals are smooth rather than brittle. If your system leans bright, Willie’s upper mids might edge forward; on a warm setup, you’ll get more air around the harmonies. This is one of those tracks that convinces you the upgrade from casual earbuds to something better isn’t about luxury so much as proximity. In the right room, with the right chain, you feel like you’ve moved closer to the footlights—an illusion of space that makes recorded music feel almost physical. If you happen to test new gear, note how the crowd’s energy sits in the stereo field and how the snare decays; that’s where the space tells the truth about the room. For those who care about gear, this is a strong demo for premium audio, but it’s also forgiving enough that a small living-room setup will still transmit the mood.

What stays with me, after several revisits, isn’t the spectacle of four icons sharing a stage. It’s the discipline of trust. They trust the lyric to carry its own freight. They trust the tempo to lean slightly forward without breakneck bravado. They trust the crowd to listen. In that trust sits the heart of the performance and, arguably, of the group itself. The outlaw posture always contained a paradox: hard edges serving tender songs. Here, that paradox resolves into a single line of motion—the train moving through the frame while we stand still and watch.

I think about three listeners as the last chorus fades. The first is a night-shift nurse driving home on an empty parkway, windows cracked, lightly dozing to the rhythm while not quite letting go. The second is a college kid with a borrowed turntable, discovering that the song his father loved doesn’t scold or preach; it travels beside him. The third is a retiree who once rode the actual City of New Orleans and now hears the clack of wheels in a room far from the rails. The song speaks to all three because it refuses to overdraw their feelings. It marks the mile and moves on.

Given how long the tune has lived—Goodman to Guthrie to Nelson to this—what’s remarkable is how gently The Highwaymen lay their hands on it. No sudden detours, no self-conscious “arrangements,” just craft. Some bands would fill the space with extra parts, or flag a finale with lighting cues; here, the musicians exit the song the way they entered: as travelers who know how to say goodbye at the station without turning it into a scene.

As for context, Live – American Outlaws isn’t a studio “album” in the conventional sense; it’s a composite portrait of a touring unit, assembled and released decades later by Legacy Recordings. That frame matters, because it means we’re hearing a document that serves memory as much as it serves catalog. On that night in 1990, “City of New Orleans” was one strand in a long rope. In 2016, presented alongside “Highwayman” and “Ring of Fire,” it becomes a study in how four distinct voices use restraint to honor a song they didn’t write and yet clearly own in performance. If you want one track from the box that shows the quartet’s shared instincts without leaning on flash, choose this one. Johnny Cash Official Site+1

And when the last chord tucks itself under the applause, you hear something else: relief. Not sentimentality, not nostalgia, but the relief that comes when music does its job and leaves you a little lighter than it found you. That, more than anything, is why this performance still travels. Play it in the quiet part of evening. Let the rhythm mark your miles. If you listen closely, the room around you turns into a platform, and the train is right on time.