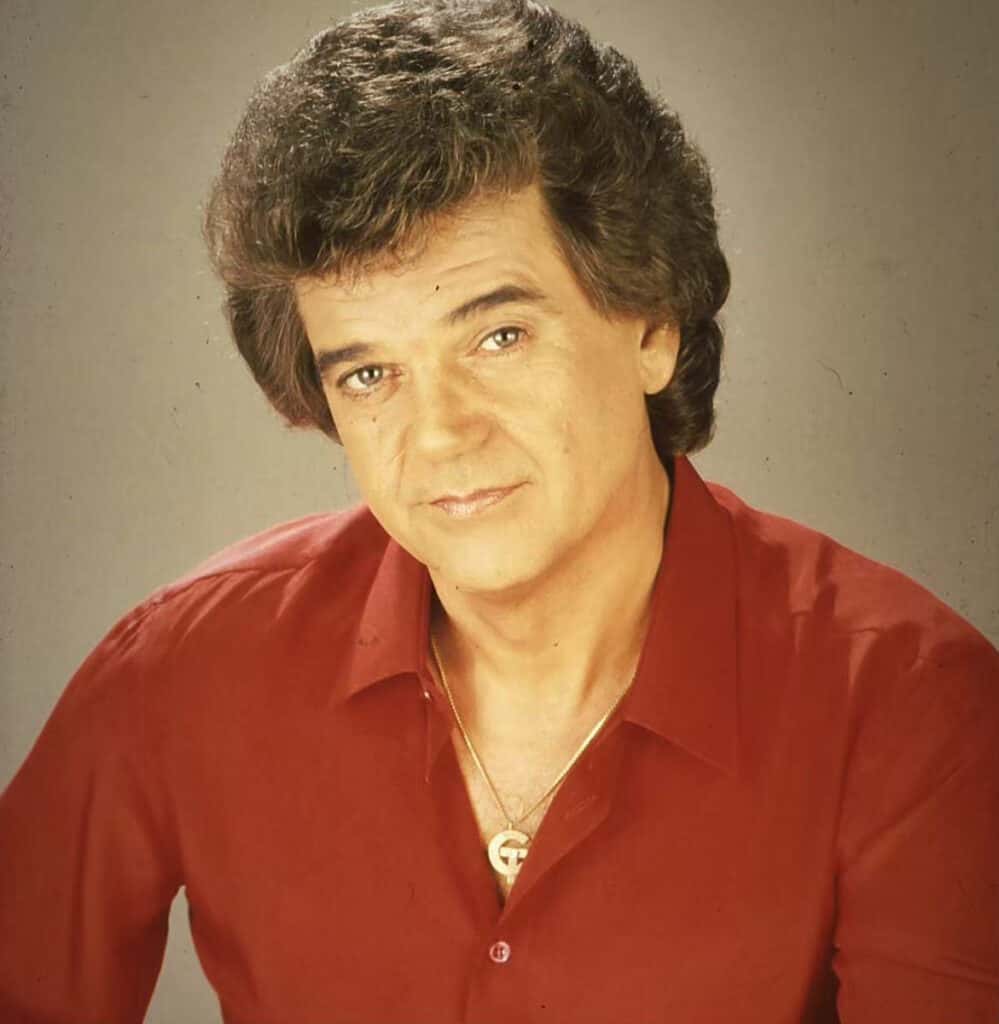

No fireworks. No headlines. Just Conway Twitty walking into a studio 50 years ago to record what they thought was just another track. But he knew differently. He was about to leave a piece of his soul on that tape, creating a moment where “the silence after the final note said more than the lyrics ever could.” We talk about legends all the time, but we rarely get to hear the exact second they were born—until now.

Conway Twitty’s “Fifteen Years Ago” is one of those late-night songs that doesn’t need to raise its voice to be heard. I picture a dim motel room on the outskirts of a small town, the bedside radio turned low, and that voice—rich, close, confessional—slipping in like a remembered scent. The story is simple: a married man meets an old friend who mentions a former love, and suddenly he’s unmoored. But the simplicity is a virtue. This is a slow-poured whiskey of a ballad, measured and adult, and it hits with the quiet force of recognition.

The facts anchor the feeling. Written by Raymond Smith, the song was released in September 1970 on Decca and produced by Owen Bradley, the architect of so much tasteful Nashville sound. It served as the title track to Twitty’s 1970 LP Fifteen Years Ago, and it climbed all the way to No. 1 on Billboard’s country singles chart, becoming Twitty’s fifth chart-topper. These markers matter because they place the record at a telling moment: the year of “Hello Darlin’,” when Conway Twitty’s style had hardened into a signature—intimate, controlled, slightly smoky, yet warm. Wikipedia+1

Bradley’s touch is audible in the sheen and space. Recorded at Bradley’s Barn in Mt. Juliet, Tennessee, the track carries that studio’s signature mix of clarity and glow. You can hear the room around Twitty’s voice: a soft halo of reverb, finely tailored, with a gentle decay that feels like the end of a thought. It’s the sort of production that doesn’t declare itself but polishes every edge—smoother than honky-tonk grit, but never so glossy that the confession slides off. Wikipedia+1

Instrumentally, the arrangement is classic Nashville: a patient rhythm section laying out a carpet of time, brushed cymbals that whisper rather than splash, and a countermelody that leans toward strings without making a spectacle of itself. The guitar stays tasteful—arpeggiated figures, a few yearning slides, maybe a bar or two of tremolo that glints like light on a windshield at dusk. A softly voiced piano enters as if sharing the secret, placing low chords under key phrases and then stepping back. The record refuses the grand, swelling arrival; instead it circles, letting the protagonist’s internal weather set the dynamics.

Twitty’s vocal is built on shading and micro-tension. Listen to the way he lands on certain vowels, letting them bend in the smallest increments, how he shortens one consonant to usher the next line, how the vibrato appears late in a phrase as a kind of afterthought. He does not plead. He does not grandstand. He practices a meticulous restraint that acts as its own form of admission. Many singers would telegraph the pain; Twitty keeps it tucked behind the teeth, and that’s precisely what makes the feeling unavoidable.

The lyric is an expert study in the geometry of memory. One casual encounter (“an old friend came by today”) triggers a cascade—the “strangers eyes” who once knew him intimately, the home he returns to, the life he’s chosen. The narrative tension arises from the speaker’s insistence that he’s fine now, that he has a loving wife, that this is a closed chapter—and the quiet terror that he might not be fully convincing himself. He doesn’t threaten to act on the memory; the stakes live in the head and heart. That’s more honest, and harder to sing.

Context matters. By 1970, Twitty had long left behind his early rock-and-roll phase (as Harold Jenkins, with the Elvis-adjacent swagger) and settled into country stardom under Decca’s banner. With Bradley producing, he found a lane where a ballad could feel like a conversation across a kitchen table at 11 p.m. “Hello Darlin’” earlier that year had cemented that persona; “Fifteen Years Ago” extends it by focusing the lens tighter, making the confession quieter, the consequences more interior. The result: a record that sounds less like a showpiece and more like a truth he can barely say out loud. Wikipedia+1

“Fifteen Years Ago” also demonstrates a lesson about dynamics that modern productions sometimes forget: the unexpected power of holding back. The drums never break stride. The bass walks, but politely. Where many ballads lean on a bridge to spill the guts, the song keeps circling its premise like a lake at night—revisiting landmarks, registering small changes in temperature, letting the gravity of what’s unspoken accumulate. You feel the refrain deepen not because the band gets louder, but because the implications do.

Part of that effect comes from the record’s sonic ergonomics. The microphone placement and the mix render Twitty’s baritone as if he’s a foot away, with air moving between him and the listener. You can almost hear the tape hiss—just a brush, setting the scene, a cue to the era’s tactile craft. It’s the kind of production that makes you want to test your studio headphones with it, to hear the sibilants and the soft pluck of the picks, to sit inside that subtle reverb tail. The music doesn’t merely play; it inhabits the space with you.

There’s also a moral seriousness to the lyric that deserves credit. Country music has never shied from messy adult truths, but not every hit treats fidelity and regret with the same sobriety. The narrator acknowledges a long-ago love that still lives in him without framing it as a romantic triumph. This isn’t a fantasy of reunion; it is a portrait of responsibility complicated by memory. The hurt is not weaponized; it is cataloged, handled with care, then placed back in the drawer—at least for tonight.

Twitty’s phrasing makes the craft look easy. He shapes each line with the sense of someone speaking carefully in a quiet house. Breath is part of the rhythm. He often tucks the tail of a phrase under the bar line, a technique that softens cadences and keeps the forward motion simmering. When he lifts into the chorus, there’s no reaching; it’s a subtle crest, like a thought clarified rather than a mood exploding.

The composition itself confirms Raymond Smith’s strong narrative instincts. The lyric turns on a small device—a chance mention—that unlocks a layered confession. The melody mirrors that motion, rising where the thought gathers weight, relaxing when the narrator tries to reassure himself. And the hook rests not on novelty, but on recognition: most adults have their own “fifteen years ago,” some name or place that returns unbidden. If the song were written today, it might arrive as a whispery Americana track; the skeleton is eternal, the clothes are just of 1970.

In the landscape of Twitty’s hits, this track functions as a middle-distance portrait between the greeting-card simplicity of “Hello Darlin’” and the duet dramas with Loretta Lynn. It is neither a pickup line nor a soap opera. Instead it’s a steady gaze into the mirror, taken at an age when love feels less like fireworks and more like the weather. Maybe that’s why it topped the country chart: plenty of listeners, then and now, know exactly what it means to be faithful and haunted. Wikipedia

When I return to the record, I keep noticing the small sonic kindnesses. The steel guitar doesn’t sob; it sighs. The strings, if present, obey the rule of two-room distance, as if they’re speaking from beyond the hallway. Even the background vocals, brief and well-behaved, sound like conscience rather than chorus. Everything is scaled to match the intimacy of the premise. In a decade known for countrypolitan sweep, this production chooses discretion over spectacle, and that choice ages beautifully.

One of the song’s subtle pleasures is the cadence of its storytelling. Verse by verse, the narrator maps a geography of temptation that never becomes a sermon. He’s not confessing to a priest; he’s talking to himself in the car, on the drive home, promising that the past will stay put and knowing it never fully does. The dramatic irony is gentle: we, the listeners, understand the fragility in his assurances because Twitty lets just enough ache seep through to make them human.

Consider, too, the record’s engineering of proximity. Bradley’s Barn was known for its balance of warmth and definition, and even if you didn’t know the location by name, your ears would recognize the vibe—clear lines, honest textures, no need to lacquer everything in echo. That aesthetic suits a story built on recollection; the sound suggests a room that is familiar, lit by a lamp rather than a chandelier. The world shrinks to a voice and a few instruments, and memory has nowhere to hide. Wikipedia

I sometimes test songs like this in modern settings—on a subway, in a kitchen at midnight, on a walk where the city’s neon makes its own kind of countryside. It holds. A friend told me he keeps it on a playlist for evenings when the day’s noise has frayed his patience; when Twitty starts, the room calms, and his thoughts line up in a gentler queue. Another listener said she hears in it the dignity of choosing the life you’ve built, even when the past taps your shoulder. These small, current-day vignettes are proof that a 1970 ballad can still speak plainly to 2025.

If you happen to be exploring this song in a hi-fi setup, resist the urge to crank it. The performance lives in microdynamics, in the soft edges. Keep the volume at a level where the breaths feel human and the string overtones bloom lightly. If you’re streaming, pick a service that doesn’t crush the life out of it; this is a masterclass in restraint, and the mastering rewards formats that let the decay breathe. If you’re on a casual speaker, it will still work; but this record repays care—think of it as a premium audio experience disguised as a barstool confession.

And because context enriches listening, it helps to remember where Twitty stood in 1970. After earlier rock and pop forays, he was in a run of country dominance, and Owen Bradley was one of the steady hands guiding that transformation. The Decca imprint signaled both continuity and craft; the charts confirmed the connection with listeners. “Fifteen Years Ago” wasn’t just a hit—it was a vote of confidence in Twitty’s mature persona, a signal that audiences wanted the man who could speak softly and still command the room. Wikipedia+1

If you’re new to Conway Twitty, this track is a near-perfect entry point. It’s adult without being self-serious, traditional without calcifying, and emotionally precise without melodrama. Call it countrypolitan if you like, but the polish here never dulls the blade. The song knows that love is not merely an event but a residue, a mark time leaves that can glow when touched by a stray remark.

Every time the refrain returns, the weight shifts slightly. That’s the beauty of memory: it doesn’t repeat, it refracts. The band keeps faith with the form, while Twitty adjusts the emotional aperture—a little more light here, a shadow there. You could chart the narrative just by tracing the reductions in his vibrato and the length of his held notes. It’s a clinic in how to act a song from the inside out.

There’s also a craft lesson for anyone who writes or arranges. Give the singer room. Use texture as character. Trust a story that rules out pyrotechnics. As a piece of music, “Fifteen Years Ago” proves that what lingers is not the number of notes played, but the proportion between voice and silence. Bradley’s production makes that proportion feel inevitable, as if any extra flourish would have been a betrayal of the truth at the song’s center.

“Restraint can carry more voltage than catharsis when the singer trusts the silence to finish the sentence.”

That line, in many ways, is the song’s ethos. It doesn’t need apology or ornament; it needs a listener willing to sit still. And in that stillness, there is a reckoning that’s tender rather than tragic. No slammed doors. No dramatic exits. Just a man telling the truth to himself in a voice that refuses to lie.

I’ll close with a thought on durability. Plenty of hits flare and fade because they were built on novelty. This one endures because it’s built on behavior. People will always encounter the past at odd angles. They will always weigh memory against promises made and life earned. A record like “Fifteen Years Ago” doesn’t tell you what to do; it simply makes a space where you can hear your own answer.

If you haven’t spun it in a while, give it a careful listen, maybe in the quiet part of the evening when the world thins out and you can hear the fret noise and the breath before the line—just enough time to feel a door open and close.

Listening Recommendations

-

Conway Twitty — “Hello Darlin’” (1970): An intimate salutation that set the tone for Twitty’s mature balladry—clean lines, close-mic warmth, and emotional economy. Wikipedia

-

George Jones — “He Stopped Loving Her Today” (1980): The ultimate study in memory’s half-life, with a gravitas that blooms from understatement.

-

Charlie Rich — “The Most Beautiful Girl” (1973): Countrypolitan polish put to narrative use, where remorse finds a radio-ready melody.

-

Freddie Hart — “Easy Loving” (1971): A smoother, sunlit complement—domestic affection rendered with featherlight arranging.

-

Charley Pride — “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone” (1970): A contemporary snapshot from the same era, balancing swing and solitude with effortless charm.