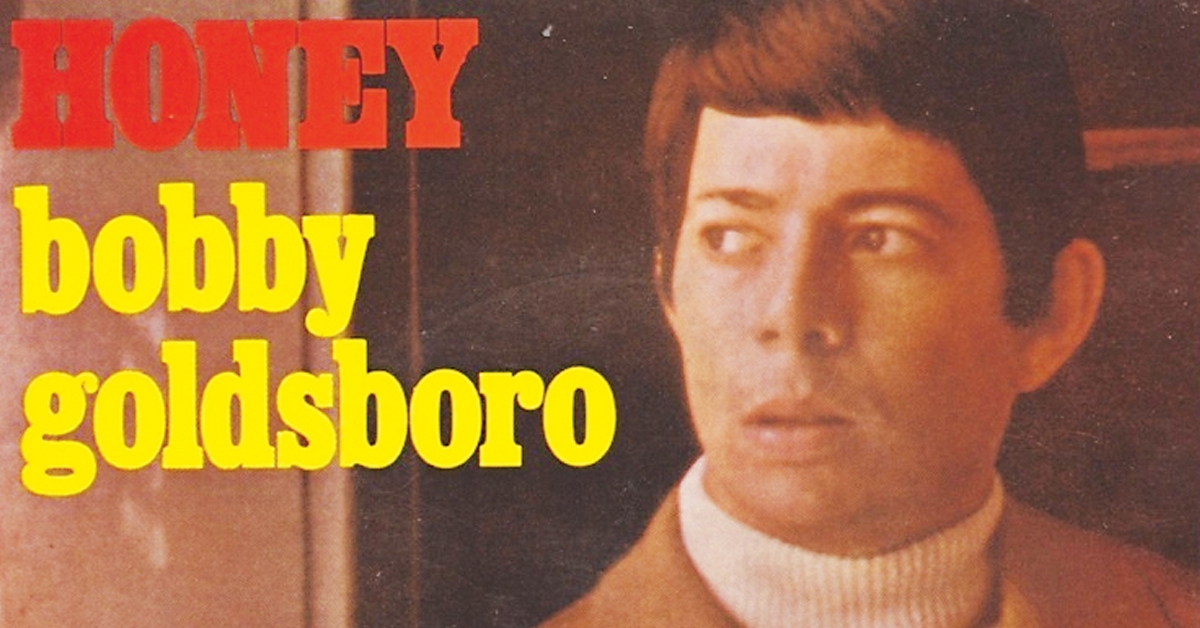

The year is 1968. The world is splitting at the seams, yet in the quiet, analog heart of the record industry, a specific, devastating kind of soft-pop is taking shape—a sound designed not for protest or psychedelic abandon, but for intimate, crushing grief. Bobby Goldsboro’s “Honey” arrives not as a whisper, but as a drawn-out sigh that somehow managed to be heard across continents. It is, to this day, one of the most commercially successful and intensely criticized pieces of music of its era.

I remember first hearing it years ago, not on a scratchy 45, but through a cheap, tinny car radio late one night, the kind of moment that locks a song into a specific atmospheric context. The drama unfolds slowly, almost reluctantly. The melody is deceptively simple, carried initially by a delicate, arpeggiated acoustic guitar line that acts as a fragile frame for the impending emotional wallop.

The Architect of Sentiment

Goldsboro was already a seasoned figure in the music industry, having cut his teeth backing Roy Orbison and releasing several minor hits. But “Honey” transcended all that. It wasn’t just a hit; it became an industry phenomenon. Released as a non-album single, it was a career pivot, defining him forever in the cultural imagination. The emotional core was derived from a poem by Barney Amburgey, subsequently set to music by Goldsboro. Crucially, the song’s signature texture—its overwhelming sense of pathos and scale—was cemented by the arrangement.

The studio craft here is immense, a testament to the lush, detailed soundscapes of late-sixties pop. While specific session details can be elusive, the arrangement is clearly of the era’s sophisticated Nashville-pop school. The song’s producer, Bob Montgomery, along with the arranger, created a chamber-pop drama. The strings, thick and mournful, enter with a heartbreaking sweep, building a wall of sound that cushions and elevates Goldsboro’s tender, almost hesitant vocal delivery. It’s a dynamic masterclass in emotional restraint contrasting with grand sonic scale.

The orchestration is the true star. Beyond the bedrock rhythm section—which plays with remarkable restraint, mostly offering soft pulses—the layering of instruments is what creates the narrative drive. The strings aren’t merely decorative; they act as a Greek chorus, mirroring and amplifying the singer’s loss. A soft woodwind element occasionally emerges, a fleeting, tender color against the dominant, weeping violins.

A Narrative Unwinds: The Sound and the Silence

The genius of “Honey” lies in its narrative structure—a series of domestic vignettes that, in their accumulated ordinariness, become gut-wrenchingly poignant after the central figure is gone. We hear about the small, charming moments: the way she’d run barefoot, her attempts at gardening, her playful inability to drive. These mundane details are the anchor, the contrast against the unspeakable silence that now fills the home.

Goldsboro’s voice is a crucial element of the tragedy. He doesn’t belt or over-emote. His tone is conversational, almost conversational, making him the narrator of a private grief, not a performer on a stage. This restraint makes the moments where his voice does crack—the audible vulnerability—all the more powerful. The melodic framework is simple, almost folk-like, relying heavily on a descending bass line that subtly but persistently reinforces the theme of decline and loss.

The piano, when it surfaces prominently, does so with a delicate, almost ghostly quality, often playing counter-melodies or adding soft chordal padding. It’s never a soloist, but a textural support, melting into the larger orchestral tapestry. To truly appreciate the subtle artistry in the production, it’s worth listening on premium audio equipment; the separation of the string sections alone is a marvel of mixing.

“The song is a Rorschach test of sentimentality: for some, a wellspring of genuine emotion; for others, an unbearable example of saccharine over-production.”

It’s easy, decades later, to dismiss the song as manipulative sentimentality. But the reaction it provoked—becoming a massive global hit, a staple of adult contemporary radio, and a song still referenced today—is evidence of its piercing effectiveness. It touched a universal nerve, the fear of losing the small, intimate constants that make up a life.

For anyone currently learning to master the nuances of pop composition, this track is a study in how to use dynamics for storytelling. Forget the easy scorn; “Honey” is a masterclass in how a song can build an entire, lived-in world out of four simple chords and a story. The final, echoing reverb tail on the last vocal line leaves a void that mirrors the narrative’s own devastating conclusion. It’s the sound of a door closing forever.

This kind of detailed, high-fidelity production for emotional impact was a hallmark of the era. The sonic ambition was huge, and it paid off. When contemplating the impact of songs that rely so heavily on arrangement, one is reminded that even the most seemingly simplistic melody can be transformed by skillful hands into a dramatic, lasting cultural artifact. The enduring quality of this tear-jerker lies in its sincerity, however polarizing that sincerity may be.

Listening Recommendations (For Fans of ‘Honey’)

- Glen Campbell – “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” (1967): Shares a similar narrative focus on domestic detail and regret, driven by lush Jimmy Webb orchestration.

- Scott Walker – “Jackie” (1967): An example of dramatic, heavily orchestrated pop where the vocal performance carries an almost theatrical, emotional weight.

- Jim Reeves – “He’ll Have to Go” (1960): A classic example of the ‘Nashville Sound,’ utilizing smooth strings and a restrained vocal to deliver a deeply felt sentiment.

- The Hollies – “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother” (1969): Another soft-rock masterpiece from the period, showcasing rich harmonies and a soaring, emotional arrangement.

- Vikki Carr – “It Must Be Him” (1967): Features a sweeping, slightly melodramatic arrangement that shares the grand, emotive scale of “Honey.”

- B.J. Thomas – “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” (1969): Possesses the same light, conversational vocal style and sophisticated pop arrangement that defined this late-60s era.