There are moments in music history that feel less like grand design and more like a happy accident caught on two-track. The moment is 1965. The air is thick with British Invasion exports, but down in Memphis, Tennessee—a town that already knew a thing or two about raw, immediate sound—a local band of high school friends called The Gentrys was wrestling a piece of music into existence. That track, “Keep On Dancing,” wasn’t meant to be a masterpiece of tape splicing, nor was it meant to be the band’s entire legacy. But sometimes, necessity doesn’t just birth invention; it delivers an enduring cultural artifact.

I was driving late last month, the kind of road trip where the radio becomes your only companion. The signal was fading in and out, the static a gritty texture against the bass frequencies. Suddenly, cutting through the haze, came that familiar, utterly uncompromising drum intro: a short, sharp snare fill that detonates directly into a rhythm track so insistent it feels less played and more demanded. It’s a sound that refuses to sit still, the perfect encapsulation of mid-sixties teenage restlessness.

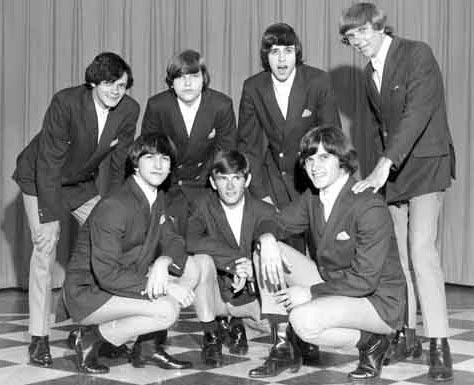

This single, originally released on the independent Youngstown label before being picked up nationally by MGM Records, was the only Top 40 appearance for The Gentrys in their initial run, peaking impressively at number four on the Billboard Hot 100. It wasn’t lifted from a conceptual album; it stood alone as a blazing, self-contained declaration of party politics. The Memphis band, which included Larry Raspberry on lead vocals and guitar, and the future wrestling magnate Jimmy Hart, bottled a kinetic energy that few could match.

The Gritty Genius of the Rhythm Section

The track’s brilliance lies not in its lyrical complexity—it is, after all, a simple plea to keep the dance floor moving—but in its instrumental architecture. It is a study in purposeful economy. Larry Raspberry’s lead guitar is sharp and economical, laying down short, treble-forward riffs that slice through the mix without unnecessary flash. It sounds like it was played through an overdriven, slightly battered amplifier, lending an unmistakable garage-rock grit to the whole affair.

The foundational groove, however, belongs to drummer Larry Wall. His work here is a masterclass in straightforward, unrelenting propulsion. The bass guitar, handled by Pat Neal, locks in tight, providing a deep, steady pulse that counterbalances the bright, almost tinny high-end. Notice the total absence of a piano or lush strings; this sound is built on the raw power of the core rock band. It’s lean, stripped back, and wholly dedicated to the rhythm. The sax line, played by Bobby Fisher, is a brief, soulful blast, adding a Stax-like echo to the arrangement but never lingering long enough to soften the edges.

This simplicity is what made the song a million-selling hit, and it’s also what contributed to its legendary construction.

The Myth of the False Fade

The story, recounted by many sources, is now studio folklore. The Gentrys reportedly only had enough recorded material for a very short song, perhaps under a minute and a half. For a track to gain significant airplay in 1965, it typically needed to clock in closer to the two-minute mark. Producer Chip Moman, a heavyweight of the emerging Memphis sound, or perhaps the resourceful studio engineer, came up with a decidedly analog solution. They took the finished, short recording, abruptly faded it out, and then spliced a duplicate of the entire first section back onto the end, kicking it back in with Larry Wall’s furious drum fill.

It is a moment of pure, audacious audio editing. When you hear the track begin its slow descent into silence—the volume dipping, the energy momentarily dissipating—your guard is down. Then, boom. That drum fill acts like a shot of adrenaline to the defibrillator paddles, instantly shocking the listener back to life.

“It is a moment of pure, audacious audio editing.”

This mechanical repetition, this accidental loop, is the single most defining feature of the piece of music. It transforms a concise garage-rock number into a dizzying, relentless dance record. The repeating structure doesn’t feel cheap or lazy; it feels necessary, an almost manic insistence on the central directive: keep on dancing. It’s a prime example of the creative limitations of mid-century tape recording becoming a strength. To fully appreciate this sonic texture, I often recommend listening on good quality studio headphones, as the subtle change in tape hiss at the splice point can be surprisingly revealing.

Echoes in the Digital Age

The enduring appeal of “Keep On Dancing” lies in its honesty. It captures the fleeting, desperate joy of a teenage moment—the crowded gymnasium, the cheap cologne, the simple, direct communication of the groove.

Today, in an era where every minute of music is meticulously curated, this track serves as a charming, slightly rebellious counterpoint. Imagine a young person discovering this track through a music streaming subscription. They might be initially confused by the strange repetition, but the raw momentum eventually wins them over. It’s a reminder that great pop music doesn’t require sonic perfection or structural complexity; it requires only an undeniable feel.

The song’s influence rippled outwards, both directly and indirectly. It was famously covered by the Bay City Rollers in the early seventies, introducing its infectious core to a new generation, albeit with a slightly glossier pop sheen. But the true spirit of The Gentrys’ original is in its raw, unfiltered power—a short, sharp shock of rock and roll energy, eternally saved by a quick snip and a careful paste. It is a time capsule of a single, unforgettable night in Memphis, now repeated forever on a two-minute loop. Give it a fresh listen. You’ll understand why the mandate to “keep on” rings true, even sixty years later.

Listening Recommendations

- The McCoys – “Hang On Sloopy” (1965): Shares the same raw, celebratory energy and tightly wound rhythmic urgency.

- Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels – “Devil with a Blue Dress On/Good Golly Miss Molly” (1966): Excellent example of a high-energy blue-eyed soul/garage-rock fusion with a similarly frenetic pace.

- Cannibal & the Headhunters – “Land of 1000 Dances” (1965): Another single from the era built on a simple, driving beat and a vocal that encourages continuous movement.

- The Bobby Fuller Four – “I Fought the Law” (1966): Features a similar bright, reverb-soaked guitar sound and an aggressively tight arrangement characteristic of the period’s best singles.

- The Capitols – “Cool Jerk” (1966): Perfectly captures the specific dance-craze context mentioned in The Gentrys’ lyrics, demanding pure rhythmic response.

- The Swinging Blue Jeans – “Hippy Hippy Shake” (1963): A prime example of an early, two-minute-long rock track that relies on relentless energy and a simple, repeating riff.