The first thing you hear is urgency. In the quiet between breaths, there’s a sense of air being shoved aside by the arrangement—horns like clipped commands, strings that tighten the frame, and a rhythm section that keeps time the way a foreman keeps time: unsmiling, precise, unyielding. Then Cat Stevens enters, young but already sounding shrewd, voice pressed forward in the mix as if he’s leaning over a counter to tell you a story before the bell rings again. The song doesn’t saunter; it punches in.

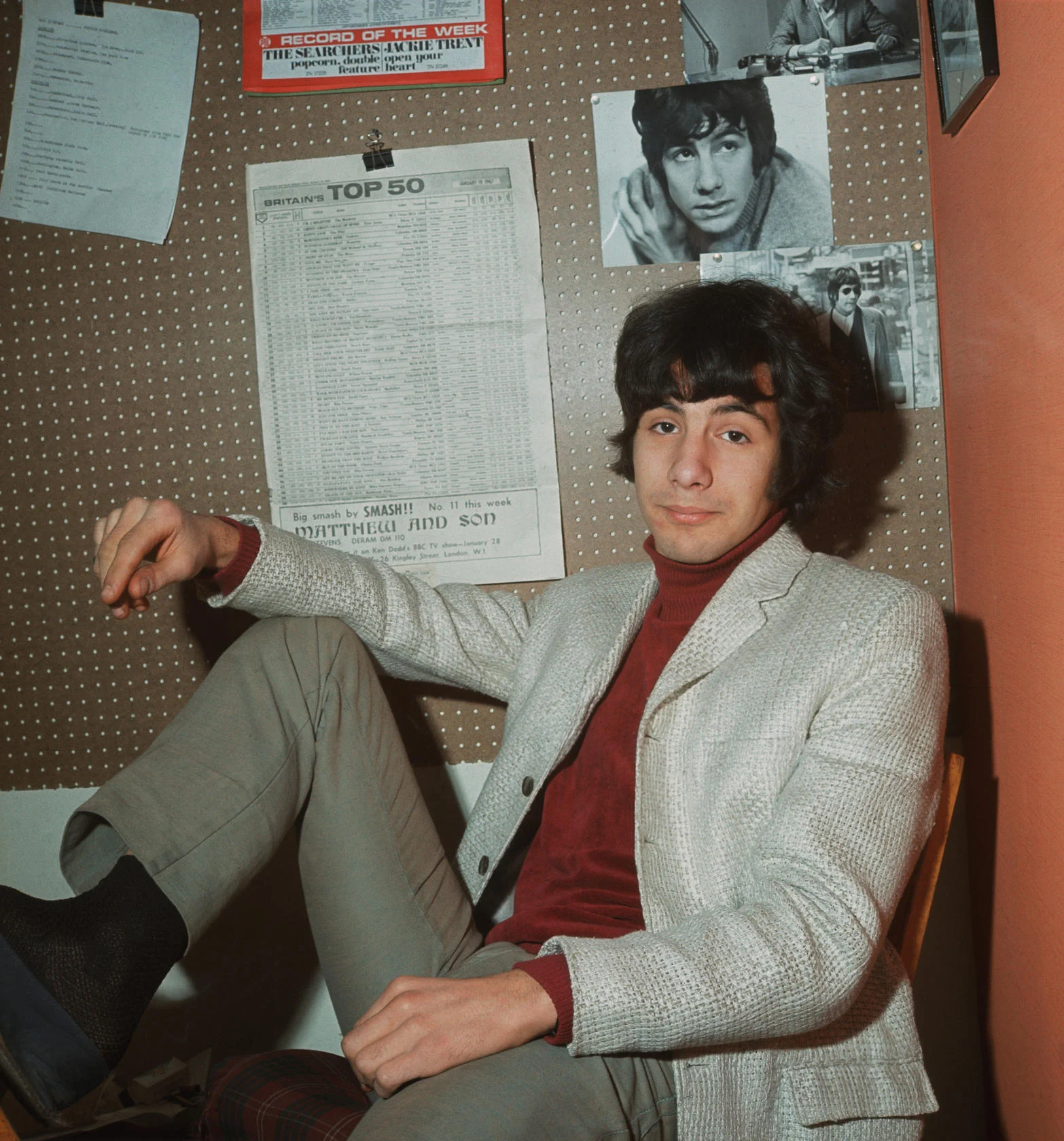

Cultural memory often treats “Matthew and Son” as the calling card of Cat Stevens’ first era, before the introspective troubadour of the 1970s arrived with open-tuned meditations and spiritual seeking. This is 1966, the cusp of 1967. London is a whirl of boutiques and new ideas, but the old order still hums: clerks, ledgers, tea breaks timed to the minute. Stevens, signed to Deram (a Decca imprint aimed at adventurous pop), glances at that world and renders it as brisk theater. The single would soon anchor his debut album, also titled Matthew and Son, and help establish him not just as a performer but as a sharp writer of social miniatures. Producer Mike Hurst, formerly of The Springfields, frames Stevens’ ideas in bright, baroque-pop colors; many sources credit arranger Alan Tew with sculpting those chic, concise orchestral lines that make the record flicker like a neon sign on a damp street.

This is a piece of music that plays like a little movie. Imagine a corridor of desks and typewriters, coats on pegs, and the afternoon light flattened by Venetian blinds. The track’s tempo simulates the rush of a city morning. Bass and drums tick with a kind of discreet force—no showy fills, just a firm grid. Over that grid, the orchestral palette is remarkably nimble: trumpets bark and retreat, woodwinds offer a brief flutter that feels like a scribble in the margins, and the strings do what good strings do in mid-’60s London pop—they tighten the screws in a way that’s half-satire, half-swoon.

I keep returning to the vocal. Stevens sounds clipped, attentive, and faintly amused, as if narrating an office brochure while slipping in subversive footnotes. He’s double-tracked in places, a classic pop technique that lends the voice body without stealing its urgency. There’s not much reverb, just enough room to suggest a studio space and not a cathedral—this isn’t confession; it’s commentary. When the chorus arrives, the melody turns a key and suddenly you’re in the most memorable hallway of the building, the one where workers line up under fluorescent lights. The hook is efficient and inevitable, a little gust of melody that carries the message without heavy lifting.

Hurst’s production flair shows in the way the band and orchestra interact. Rather than drape everything in plush strings, the arrangement uses stabs and dovetails. One section makes a point; another answers with a smirk. On the bridge, when the perspective widens to take in the scale of the company, muted brass enter like an executive cough. The percussion is tidy—snare crisp, hi-hat abbreviated—so that nothing interferes with the song’s essential gait. If the era’s broader British pop leaned toward psychedelia or folkishness, “Matthew and Son” chooses crisp realism, the sonic equivalent of a pressed shirt.

And yet it glitters. Baroque pop is often remembered for its ornamental drag—harpsichords and chamber strings slung over melodies like costume jewelry. Here, the ornaments are structural. The little fanfares aren’t winks; they’re timestamps. They tell you when the clock changes, when the task begins, when the next line is due. The orchestrations compress a day’s bureaucracy into three tidy minutes, and because they do, the satire lands with a gentle sting. Stevens isn’t pitying his characters; he’s cataloging the mechanisms that shape them.

“Matthew and Son” sits at an interesting junction in Stevens’ career. He’s very young, but the writerly instincts are already sharp: specific images, social frames, and melodies that click shut like a well-made clasp. The single arrives on Deram at the end of 1966, and by early 1967 it’s moving decisively up the British charts. That broad success would launch a busy period of writing and recording before illness and reorientation in the late ’60s, and before the re-emergence in the early ’70s on a different label with a stripped, personal aesthetic. If you know the honeyed acoustics and contemplative tone of those later records, hearing this brisk office drama is like discovering a youthful sketch that already contains the artist’s wit, only cast in fluorescent light instead of candle glow.

Listen for the way the melody turns on consonants. Stevens leans into hard sounds, keeping his articulation crisp. Each verse is a little ledger: items listed, expectations noted, a life’s tempo set by the bell. Then the chorus opens its arms, and the orchestration rises a half-step as if to say: we understand, we have seen this too. The emotional architecture is empathetic without being sentimental. It invites you in with a showtune’s clarity and leaves just enough oxygen for your own memories to take root.

Now consider the textures. The acoustic foundation is joined by a rhythm section that moves like a small machine. Brass come in short bursts, strings in quick rakes and long-bow sustains, plus woodwinds that draw light pencil lines along the edges. Somewhere in the weave, a keyboard figure adds percussive brightness—call it the desk lamp of the arrangement. You can hear the care with which frequencies are distributed. Nothing splashes. The center stays open for the story.

There is a subtle theatrical lineage running through the track. The call-and-response elements, the tightened rhythms, the way sections present and dismiss themselves—these make the song function like a miniature revue number, a five-o’clock curtain raising on an everyday drama. Yet it never tips into pastiche because Stevens keeps the writing grounded in details and the production resists bombast. The key to its charm is control. The band is crisp; the orchestra is quick; the singer is exact.

Here’s what separates “Matthew and Son” from a lesser office satire: compassion. The song describes schedules and demands, but you can hear Stevens holding a space for humanity within those routines. He’s not sneering at clerks; he’s noticing how systems turn time into a commodity. That’s why the record still feels current in the age of shared calendars and blinking notifications. The specifics have changed; the pressure hasn’t. You can almost transpose the arrangement to an open-plan coworking space today and the rhythms would still fit.

A brief word about the soundstage. Mid-’60s British pop singles were often mixed for impact on small speakers and transistor radios. This track honors that tradition with a forward vocal and compact bass. Listen on modern gear and you’ll notice the mix is tight in the center, built to speak clearly on a variety of systems. The brass are deliberately punchy, not roomy; the strings carry body without boom. Play it on good studio headphones and you’ll hear the dovetailing parts click together like clock teeth.

Hurst’s production also foregrounds contrast. Verses feel like corridors; choruses open up like stairwells. The arrangement is not lush in the syrupy sense—it’s busy and purposeful, the musical equivalent of office stationery laid out with immaculate care. Many sources note the presence of Alan Tew’s arranging hand, and it fits: brisk lines, neat turns, and an overall clarity that keeps the song’s social point audible through the entertainment.

I think about the lives that fit inside this track. A student on a weekend job, counting coins and minutes. A mid-career parent learning to live by run-on calendars. A retiree who still wakes at 6:30 because decades set the muscles to it. The record sits on a shelf of British baroque pop that includes satirical portraits and domestic epics, but it remains singular, not because its picture is clearer, but because its sympathy is. Stevens sings what he sees, and the arrangement amplifies the observation without trampling it.

Pull back for a second and look at the arc. Within a few years, Stevens would pivot toward acoustic introspection, writing the kind of songs that feel like conversations with a friend at a kitchen table. You can trace the line from here to there: the eye for ordinary life, the clean melodic sense, the control. If later work is about inner rooms, “Matthew and Son” is about outer rooms—offices and schedules—drawn with the same care.

Now the micro-stories, because this is how songs travel. I once heard the track on late-night radio while driving past an industrial park, the fluorescent spill from a lone office window lighting a strip of wet pavement. The horns cracked through the static and, for a moment, the empty parking lot felt crowded with invisible workers clocking out. Years later, in a café where the wall calendar still had months from the previous year, a barista rinsed pitchers while the chorus bounced off tile and glass; a student at the corner table drew a timetable for the week, mouthing along. More recently, a friend in a start-up sent a message: “This is our theme song, in a way.” The mechanism changes—pagers to push alerts—but the tempo of expectation does not.

The guitar appears not as a folkish headline but as a rhythmic actor, woven into the machinery, steadying the groove when the orchestral jabs threaten to take all the oxygen. A few bright strums sharpen the downbeats, leaving plenty of space for the brass figures to punch through. The piano, meanwhile, adds percussive diction, sealing the syllables of the rhythm in a way that almost suggests a typewriter carriage. In lesser hands these balances would feel busy; here they feel inevitable.

What about the words? Without quoting, we can say they stack up like noticeboard items—wages, hours, rules—and then step back to reveal the human outline those bullet points describe. The satire is mild enough to be hummable in a company lift, sharp enough to make its point. That balance—hook and critique—is the secret. Plenty of pop songs of the era comment on society; fewer do it with this much formal wit.

If you’re curious how the record sits inside its discography, the answer is: at the front door. “Matthew and Son” is not a cul-de-sac; it’s a hallway that leads to many rooms. The topical precision of the writing points forward to narrative gifts he would deepen later, even as the orchestral pop frame belongs firmly to this first phase. If you approach it from the ’70s albums, it can feel like an exuberant cousin; approach from mid-’60s London pop, and it feels like an exemplar—swift, sharp, and friendly.

There’s also an element of empathy baked into the tempo itself. Fast songs often celebrate speed; this one uses speed to show constraint. That is clever craft. The band hustles, but the music’s smile is knowing. When the final refrain lands, you hear not triumph or tragedy, but recognition. Pop can do many things; one of them is to make recognition pleasurable.

The record moved briskly up the charts in early 1967—high enough to become unavoidable in Britain—and its presence on the debut album consolidated Stevens’ arrival as a writer with an eye for the fabric of everyday life. That status matters. It reminds us that pop’s supposed lightness can carry social data without turning into a sermon. It reminds us that a three-minute single can be architecture.

“Great pop doesn’t just mirror life; it re-times it so we can hear the heartbeat hiding under the schedule.”

If you’re approaching the track today, you might be tempted to chase a remaster or compare mono and stereo presentations. That’s fine, but don’t let format hunting overshadow the song’s essential snap. The mix’s compactness is a feature, not a bug. Play it loud enough to feel the brass convulse and the strings tighten. Then notice how the vocal rides everything with conversational ease, as if Stevens knows you’re halfway to the next meeting and only has a minute to make his point.

For musicians and curious listeners, there’s another pleasure: the way the melody threads the changes while respecting the song’s commuter-train momentum. I’ve seen people reach for sheet music to parse how the chorus flips mood without contorting itself. That kind of economy is difficult; it takes the confidence to do exactly what’s needed and then get out of the way.

So why does “Matthew and Son” still work? Because it catches something permanent. Schedules, bosses, expectations—these recur in different guises. The record packages that truth in vivid, compact theater. It’s not a protest anthem; it’s a portrait with clear lines and bright paint. And like all good portraits, it sees the person, not just the frame.

When the final notes stop, there’s a pleasant afterimage: a corridor, a clock, a group of workers stepping out into the street, the night air unmeasured for a moment. Play it again and the corridor returns, but so does the sly smile in the vocal, as if to say: you know this place, and now you have a tune to walk it with.

Listening Recommendations

The Kinks – “A Well Respected Man” (1965): Wry social portraiture with clipped, British invasion swagger and a strut that mirrors office routine.

The Hollies – “Bus Stop” (1966): Everyday romance painted in sharp lines and chiming arrangement; neat, economical storytelling from the same era.

Cat Stevens – “I Love My Dog” (1966): Early Stevens on Deram, gentle baroque-pop frame and writerly tenderness that hints at the songwriter to come.

The Left Banke – “Walk Away Renée” (1966): Baroque strings and pop clarity; a model of how orchestration can shape emotion without excess.

The Bee Gees – “New York Mining Disaster 1941” (1967): Narrative pop with stark imagery and harmonies that carry social weight inside a tidy runtime.

The Beatles – “Penny Lane” (1967): Orchestral pop vignettes of everyday life, arranged with luminous detail and an eye for civic choreography.