The first thing you hear is softness—a cushion of strings inhaling, as if the orchestra takes a breath for you. Then the voice arrives, clear but rounded, and a small drum figure marks the shape of a memory that won’t quite fade. “Here It Comes Again” is, at heart, a mood suspended in amber: the moment you feel a recollection approaching and realize there’s nowhere to hide. In three minutes, The Fortunes capture that sensation with a high-gloss melancholy that feels distinctly mid-sixties but never trapped there.

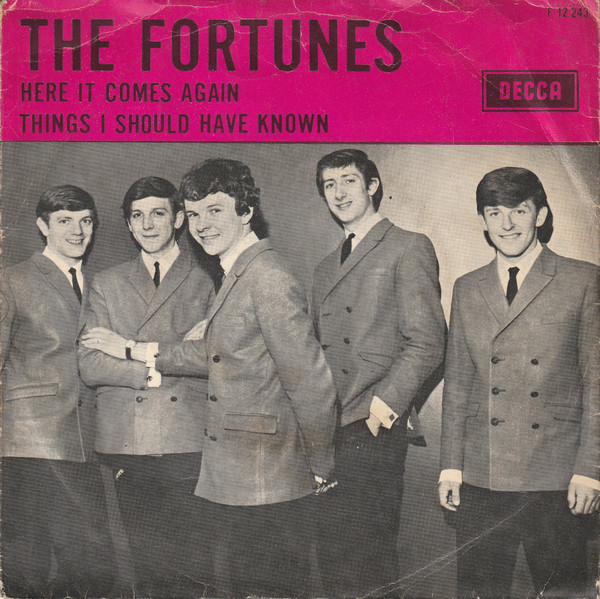

This track entered the world in 1965 as a standalone single on Decca in the UK, a swift follow-up to the band’s breakthrough with “You’ve Got Your Troubles.” The Fortunes were one of those British groups that specialized in radiance—the kind of harmony singing that could polish sadness until it glowed. Many sources credit John Schroeder on the production side with Les Reed providing the arrangement, which aligns with the record’s polished orchestral language and tasteful dynamics. The group’s arc in this era is a study in sleek pop discipline: present the song as a star, then frame it with the band’s voices and an elegant studio halo.

The writing itself bears fingerprints of the British pop craft machine—melody first, melody last, and melody everywhere in between. While the hook is simple, the song’s power lies in how it returns, how it circles. You feel the title as a pulse rather than a slogan. The lyric doesn’t sermonize; it observes, gently, almost resigned. This is heartbreak that understands its own ritual. The Fortunes’ delivery makes the ritual feel ceremonial, even necessary.

Think of the record as a room. The walls are made of strings, joined at the corners by woodwinds that appear and recede like tasteful trim. The ceiling is a lightly reverberant space the vocal can lift into without becoming mist. The floor—solid and unassuming—is a rhythm section that barely announces itself, working in rounded thumps and soft brushes. The result is an illusion of stillness. You’re moving, but everything feels suspended, as though the song has slowed time just enough to show you the path back to what hurts.

The lead vocal—reportedly by Rod Allen—does the hard work of sounding effortless. There’s a careful way he softens consonants at the ends of lines, which adds to the sense of a memory melting instead of breaking. The vibrato is controlled, a camera focusing rather than a siren calling attention to itself. When harmonies bloom, they don’t stack like architecture; they float, then settle, like swans aligning on a lake. If you listen closely on a good system, there’s a felt presence to the backing voices as they arrive—one of those moments where you’re reminded that pre-digital pop still prized the weight of air in a studio.

Instrumentally, the record plays sparingly with contrasts. There’s, by design, very little grit, but it isn’t a sterile shine. A plucked line flickers under the choruses, a gentle percussion figure turns the corners of the form, and the strings negotiate between sigh and glide. A small glint of brightness, possibly a celesta or lightly touched keys, peeks out to add shimmer in transitions. The arrangement understands that movement can feel luxurious when it’s subtle. You don’t need fireworks when the moon is already the show.

The mix feels decisively mid-sixties: vocals front, instruments arranged like a semicircle, a light plate reverb creating a short tail that never overwhelms the words. That sonic decorum is part of the charm; even the crescendos feel mannered. It invites you to lean in rather than press back. If you’re evaluating the fine grain of the timbre—attack on the strings, the way the room responds to the voice—you can almost picture the faders nudged with conservative confidence. There’s no bravura in the engineering; there’s a quiet trust that the song is already doing the emotional lifting.

I’ve always heard “Here It Comes Again” as the slower breath after a heavy year. Imagine late October, a café window fogging over, and a friend you once made plans with walking past without seeing you. The song narrates that small ache with poise. It’s not an argument; it’s the weather of feeling. If “You’ve Got Your Troubles” was the headline, this is the analysis in smaller type—cooler, but perhaps closer to the truth of how heartache actually lives day to day.

Because this is such a meticulously balanced piece of music, every element has to be exact. One extra flourish and the spell would wobble. One less, and the track might sink into anonymity. The Fortunes thread the needle through a vocal center that sounds immune to panic. The calmness is not indifference; it’s containment. In an era when many acts chased sonic novelty or raw punch, The Fortunes built a habitat for tenderness and relied on craft to keep it from curdling into sentimentality.

There’s also the band’s identity to consider. British beat groups often faced a choice: lean into R&B-flavored drive or embrace orchestral pop elegance. The Fortunes tilted toward the latter without losing the accessibility of a chorus you can hum on first listen. They weren’t as baroque as later chamber pop, nor as sparse as Merseybeat minimalism. The balance they found—clean harmonies, string-embroidered arrangements, dignified rhythm—turns “Here It Comes Again” into a small masterclass in proportion.

From the vantage point of 1965, you can hear how the single participates in a broader conversation on the charts. Orchestral pop, sometimes called “soft beat” by contemporary press, was enjoying a rich season. Records by the Walker Brothers and Dusty Springfield were showing how much drama could be pulled from restraint. “Here It Comes Again” sits in that lineage without imitating anyone’s wardrobe. It wears its melancholy with a well-cut suit and lets the melody do the talking.

The lyric’s recurrence is its thesis: inevitability. Feelings recur because memory has muscle. The Fortunes handle that idea with empathy. They never weaponize nostalgia; they decorate it. The chorus doesn’t escalate so much as return with clearer definition each time, and that choice becomes the emotional architecture of the track. You come away with the sense that acceptance can be tender—and that tenderness can be a form of strength.

As a single, the song helped cement the band’s reputation beyond a one-hit narrative. It charted respectably in the UK and made its presence known in the U.S., which is no small feat for a group working in the smoother end of the British Invasion spectrum. Over time, it has become a reliable highlight on compilations and reissues, standing shoulder to shoulder with the better-known A-sides and revealing itself as a companion piece rather than a mere follow-up. When you sequence their material, this track often provides the deep exhale that makes the surrounding brightness feel earned.

One audio note: the recording’s top end can sound a touch glassy on some modern remasters, especially if you’re listening on overly bright gear. The midrange, where the voice lives, is the money band here. If you can, give it a spin on equipment that honors the warmth without turning the strings into glare; you’ll catch the elegance of the blend and the subtle breath in the room. It’s the kind of record that rewards careful listening more than casual blasting, more library than dance hall.

“On this record, sorrow isn’t an event—it’s a texture, ironed smooth until it shines.”

That texture reveals itself in the little details. The moment a harmony tucks under the lead and lengthens a syllable by half a beat. The way a string line rises not to announce climax but to shade the word it accompanies. The tiny swell before a chorus that feels like the lift of a curtain rather than the strike of a match. These are not tricks; they are manners—and manners can be musical virtues when the subject is a heart trying to behave itself.

The Fortunes were never radicals, but they were impeccable stylists. That distinction matters. The sixties produced plenty of groundbreaking records that changed what was possible; it also produced records like this that perfected what was already possible. “Here It Comes Again” doesn’t want to reinvent your idea of pop; it wants to touch your idea of poise. And in 1965, with studios becoming ever more sophisticated and arrangers like Les Reed proving that strings could be modern rather than musty, the song felt aligned with the times.

Listen closely for how the rhythm section behaves. Rather than driving, it brackets the phrases. The bass supports but rarely insists; the drums mark the bar lines with a professionalism that asks to be felt more than heard. A small guitar figure provides gentle filigree, a reminder that even within orchestral decor, the band remains the band. There’s also a discreet moment where the piano underlines a harmonic turn, almost like a knowing nod from the corner of the room. These quiet gestures form the record’s personality.

If you come to the song today, maybe through a playlist that folds British mid-sixties pop into a Sunday routine, it still feels functional in daily life. I’ve watched it rescue a late night at the desk when a document refused to finish itself. I’ve seen it temper the odd rush of a crowded bus as rain freckles the windows. A friend told me they use it as a reset after difficult phone calls; it returns the room to neutral the way only a familiar refrain can. The record is practical, which is not a word we often grant to pop balladry. But practicality—music that behaves like a lamp, a chair, a window—is why songs like this endure.

Collectors will tell you that original UK pressings deliver a certain buoyancy the later cuts sometimes sand down, and while we can debate the finer points of mastering, the core experience stands regardless of source. If you’re the type who notices engineering detail, you might appreciate how the orchestration leaves air around the vocal line. It’s an arrangement choice that feels confident: a belief that stillness can be dynamic if framed with care.

Should you want to follow the melody on your own instrument, editions of sheet music have circulated for years, and they underscore how straightforward the harmonic skeleton is. The sophistication lies not in the chords but in how the performance breathes around them—timing, blend, phrasing. That’s why simple songs often survive best; they offer more room for the air that makes recordings human.

As for where it sits in The Fortunes’ canon, it feels like a hinge: proof that “You’ve Got Your Troubles” wasn’t a fluke, and a statement that the band could render sadness with the same reliability they brought to more upbeat fare. While later releases would take them into different territories, this single captures the essence of their early promise: sleek melancholy, disciplined harmony, and a studio sheen that never quite turns impersonal.

What lingers most is how the track dignifies repetition. The return of feeling isn’t dramatized as catastrophe; it’s acknowledged as routine. The Fortunes offer comfort by recognizing that the second, third, tenth wave of memory is part of the human schedule. You don’t conquer it; you prepare a place for it. And when the last chord settles, you sense that the door is still open for whatever comes next, good or otherwise.

One last listening tip: try the track once with good studio headphones and notice how the strings sit just behind the vocal, like a curtain half-drawn across a sunlit window. The panorama is restrained, but the depth is there—more theater than stadium, more invitation than declaration. It’s music that understands how to be near.

If The Fortunes never quite achieved the mythic profile of their flashier contemporaries, a record like “Here It Comes Again” argues for a different kind of legacy: craftsmanship as a virtue, elegance as an ethic. You leave the song not chastened but steadied, as if someone you trust has confirmed that your feelings are ordinary and therefore survivable. And that is a gift worth revisiting.

Listening Recommendations

-

The Fortunes — “You’ve Got Your Troubles” (1965): Sister piece in mood and arrangement; the same velvet harmonies carry a sharper ache.

-

The Walker Brothers — “Make It Easy on Yourself” (1965): Orchestral pop at symphonic scale, where restraint becomes grandeur.

-

Dusty Springfield — “I Just Don’t Know What to Do with Myself” (mid-60s): Bacharach-crafted melancholy with string drama and impeccable phrasing.

-

The Zombies — “Tell Her No” (1964): Tight harmonies and cool emotional temperature, balancing intimacy and polish.

-

Herman’s Hermits — “No Milk Today” (1966): A bright surface with shaded sadness beneath, arranged with nimble orchestral touches.