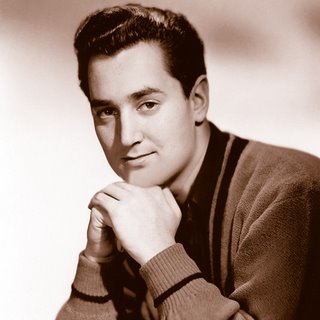

It begins with a hush—strings poised like breath held before a confession. Then the voice, instantly personable, steps forward with that light, elastic tenor Neil Sedaka could place right on the center of a melody. “You Mean Everything to Me” is the kind of ballad that arrives without fanfare and quietly rearranges the room. You can almost picture the red bulb glowing outside a live room door, a conductor lifting a hand, tape rolling, musicians fixing their eyes on the downbeat. That is the atmosphere this recording conjures, an intimacy framed by orchestral grace.

Let’s set the context plainly. The song was first released as a single in 1960 on RCA Victor, co-written by Sedaka and his longtime collaborator Howard Greenfield; it would become one of the key early sides that established his chart presence. Wikipedia In the U.S. it rose into the Top 20 and performed even better in Canada, evidence that Sedaka and Greenfield’s conversational lyricism had international reach. Wikipedia+1 Though it later turned up on a 1961 release that gathered several of his breakout 45s, “You Mean Everything to Me” was born as a stand-alone statement in the 45 era, a format perfect for miniature dramas that played out in under three minutes. Wikipedia

Crucially, the arrangement bears the fingerprints of Stan Applebaum, whose charts for pop singers in this period threaded a very specific needle: lush but never syrupy, dynamic but never showy. Applebaum is documented as the arranger-conductor on this title, and you can hear why Sedaka’s team kept returning to him. discogs.com+1 He sets the scene with a gauzy bed of strings that swell on cue, woodwinds that answer the vocal with soft curlicues, and a rhythm section that favors cushion over punch. The percussion is tucked back; the bass moves with polite certainty. The effect is to keep the voice forward, like a spotlight on a stage with the curtain only half open.

From a purely sonic perspective, the recording is about proximity and restraint. The vocal sits close to the microphone, just shy of sibilance, so you catch the air in Sedaka’s consonants and the light taper on his vibrato. Reverb is present but not cavernous; it lingers like the tail of a candle’s smoke rather than a plume. The string lines glide rather than tug, and when they crest into the refrain, they work as emotional underlining—not a substitute for feeling but a frame that amplifies it. You could call this a small-room ballad blown up to cinema size, yet the core remains modest, assured, conversational.

Listen to the way Sedaka shapes phrases in the verses. He tends to land on the emotional word with a soft weight, never squeezing for effect. It’s a singer’s reading, to be sure, but also a songwriter’s. He knows the syllable that does the work, and he points to it without underlining twice. That’s part of why the piece of music feels durable: it’s arranged for strings and sweetened for radio, yes, but at heart it’s a tidy melody that could survive with only voice and a few chords.

There’s a lineage at play. Many have noted how Sedaka’s early ballads share DNA with late-’50s and turn-of-the-’60s teen-pop torch songs—think Paul Anka’s poised declarations—but “You Mean Everything to Me” leans less on bravado and more on gentleness. Wikipedia The lyric’s simplicity is disarming. It doesn’t hunt for metaphor; it names a feeling and stands by it. The trick, if you can call it that, lies in how the melody steps upward and then relaxes, mirroring the way a nervous admission gives way to ease. Nothing is wasted. Two and a half minutes, a single ground-floor emotion, and we’re out.

Because the recording is so focused, tiny timbral choices matter. Plucked strings appear sparingly, like a hand placed lightly on a shoulder. Sustained violins become a kind of halo, a glow that never blazes to white. There’s likely a room sound that favors the middle—no hyped bottom, no glittering top—so that everything lives in a warm, breathable band. The result is a sonic photograph without harsh contrast. You hear edges, but they’re soft-edged, fully 1960 in their balance.

Sedaka’s own musicality is central. He was a trained pianist long before the hits, and you can sense a keyboardist’s logic in how the melody is built: stepwise motion, clear cadences, no gratuitous jumps. Even when you can’t isolate a prominent piano line in the mix, the songwriter’s feel for chordal gravity is everywhere in the vocal path he traces.

If you want a full career vantage, this single stands near the beginning of Sedaka’s first run as a chart presence: the same window that produced “Stairway to Heaven,” “Run Samson Run,” and later “Calendar Girl,” all Greenfield co-writes that balanced teenage earnestness with adult craft. Wikipedia What’s revealing is how often Sedaka returned to “You Mean Everything to Me” in performance over the years—1968 included—almost as if to remind audiences that beneath the playful uptempos he could inhabit a ballad with straight-backed sincerity. Facebook

The orchestral design deserves a closer pass. Applebaum’s charts typically assign woodwind figures as interior voices, a kind of living pad in place of an organ. Here, you can hear clarinets and flutes trade little handoffs under the strings. The bass does not walk; it leans. Drums mostly ride the cymbal, which gives a sustained shimmer rather than percussive punctuation. Guitar shows up like a polite guest—clean, supportive, no twangy asides—filling chordal space without trying to carry it. The point isn’t virtuosity; it’s blend.

This is also why the record ages well in an era of overstatement. The dynamics bloom and recede. There’s no compulsory key change to signal “big finish,” no dramatic breath intake telegraphed as climax. What you get is steadiness, a tone of voice that assumes the listener is already leaning in. The more you play it, the more you start to notice artisanal details: how the first refrain is held back a notch, how the second returns with just enough swell to feel like an answer, how the final cadence avoids a show curtain and instead lets the moment drift.

I’ve often thought about who this song speaks to now. On a late-night drive, it works as a kind of interior monologue: your headlights carving a cone through the dark while Sedaka tells you a simple truth you might be too proud to say aloud. In a kitchen on a Sunday morning, it’s the record you put on while you’re slicing fruit, its core message making the quiet domestic scene feel like a vow. And in a crowded café, buried in a playlist, it still lifts its head—because the arrangement refuses to jostle and the voice refuses to posture.

One of Sedaka’s feats is how he leverages scale. The orchestration says “grandeur”; the performance says “whisper.” This tension—glamour versus plain-spoken confession—gives the recording its shape. It belongs to the same family as early-’60s pop balladry, but it dodges the melodramatic traps that date lesser examples. Even the string swells feel like breath rather than thunder.

Consider the lyric’s economy. There’s no narrative arc in the strict sense, no verse that turns the story sideways. Instead the narrative is musical: each time the hook returns, Sedaka’s timbre shifts—a touch more open, a shade more luminous—as if the singer has gained the courage to inhabit the words fully. That is a kind of story, and a believable one.

“Songs like this don’t plead for attention; they invite you to notice the craft, then slip gracefully into your memory.”

Because listeners ask: where does it sit in Sedaka’s broader discography, and who helped it sound this way? The paper trail is clear enough to keep us honest. The single credits RCA Victor and ties the recording to Sedaka’s Aldon circle with Greenfield; Applebaum’s role as arranger and conductor is well-documented across sources. Wikipedia+2discogs.com+2 Chart-wise, you can safely place it in the U.S. Top 20 for 1960 and note the Canadian showing near the summit. Wikipedia If you’re looking for it on a longer-form release, you’ll find it collected the following year among other 45s. Wikipedia And if your reference point is a television clip you saw from the late 1960s, that lines up too; Sedaka was still giving the song fresh life onstage around 1968. Facebook

When we talk about arrangements from this era, we sometimes miss how deliberately they were engineered to carry on radios both cheap and dear. This record is a masterclass in midrange authority—you could play it through a tiny portable or a furniture console and the essence would remain. The voice rides the center; the strings glow just above; nothing booms, nothing fizzles out. If you happen to audition it today on modern gear, the modesty of the master is part of the charm. Audiophile fireworks aren’t the point; the point is balance.

Still, the musicianship rewards close listening. Put on a good pair of studio headphones and focus on the inner voices: you’ll catch call-and-response figures that do their work almost subliminally, directing your attention exactly where the producer-arranger wanted it. The take feels finished in the old-school sense—an ensemble walking into a room to make something together, not a stack of overdubs engineered for spectacle.

There’s also an intergenerational appeal that has less to do with nostalgia than with clarity. The lyric’s plain declaration gives younger listeners an anchor; the orchestration gives older listeners a familiar texture; the vocal bridges the two with a kind of dignified warmth. It’s a rare triangle. That might be why cover versions sprouted in multiple languages and why Sedaka himself recorded a Hebrew take—proof that the melody travels well and the message travels further. Wikipedia

In terms of instrument roles, note the gentle dialogue between sections. The strings state the emotional weather. Woodwinds paint in the smaller clouds. Guitar fills out harmony with discretion, avoiding busy arpeggios or blues flourishes. And somewhere in the mix, the keyboardist’s sensibility guides harmonic pacing—the ghost of a piano player embedded in the song’s spine even when keys aren’t foregrounded. Nothing strives for attention; everything contributes to ease.

If you’re a musician tempted to bring the song into your repertoire, the harmonic movement is forgiving yet satisfying—diatonic with a few well-placed lifts. Lead sheets are widely available, and the melody sits in a comfortable range for multiple voice types, which helps explain its long life on variety shows and in cabaret settings. If you’re the sort who likes to learn songs from the page, you’ll have little trouble finding the sheet music.

Fans sometimes pit Sedaka’s rhythm-forward hits against his sentimental sides, but that misses how much these modes talk to each other. The buoyancy of his uptempo writing sneaks into the phrasing here—notice how the line endings feel just a touch anticipatory, less crooned than set gently on the beat. That rhythmic poise keeps the track from slumping into mush; it moves even when it sways.

And what of the final impression? For me, it’s the sensation of a curtain falling without fanfare. No grand ritard, no timpani roll, just a courteous farewell. You realize, after the last chord dissolves, that the most extravagant thing the record does is remain small. It respects your space. It assumes your intelligence. It knows the difference between drama and presence.

One more historical thread is worth a nod. By the late ’60s, the pop landscape was shifting toward rock’s bigger canvases and singer-songwriters’ bare confessionals. That Sedaka could lift a 1960 ballad into 1968 television sets and still make it feel current says something about the song’s architecture. It’s built on clean lines. Swap the arrangement, and it survives. Leave the arrangement, and it glows. That is not common.

If you’ve come here because the title in your head reads “Neil Sedaka 1968 – You Mean Everything to Me,” be assured the timeline aligns: the record’s birth certificate says 1960; the late-decade performances kept it in public view. Wikipedia+1 Either way, the heart of the matter doesn’t change. What Sedaka captured—and what Applebaum framed—was a modest profession of love that staked everything on tone.

So take a quiet evening, dim the lights just a touch, and let the song play from start to finish without interruption. You may find that it asks nothing of you except attention, and it rewards that attention with a feeling more durable than nostalgia: calm recognition.

Listening Recommendations

• Paul Anka – “You Are My Destiny” — A late-’50s template for string-led confessionals, similar poise and melodic clarity.

• The Everly Brothers – “Let It Be Me” — Intimate harmonies and orchestral softness that cradle a simple vow.

• Ricky Nelson – “Lonesome Town” — Sparse, echo-kissed melancholy that shows how understatement carries weight.

• Connie Francis – “Where the Boys Are” — Early-’60s ballad sweep with cinematic strings and a pure vocal line.

• Neil Sedaka – “I Must Be Dreaming” — Another early Sedaka-Greenfield study in gentle phrasing and tidy structure.