The air in an Olympic Studios control room in 1966 must have been thick with ambition. You can almost feel the phantom weight of it now: the low hum of valve amplifiers, the scent of magnetic tape, and the quiet confidence of a young Mick Jagger, not as the preening frontman, but as the producer. He was there to capture a force of nature, a voice that could strip paint from walls and break hearts in a single phrase. That voice belonged to Chris Farlowe.

The song was “Out Of Time,” a Jagger-Richards composition tucked away on the UK version of The Rolling Stones’ album, Aftermath. The Stones’ own take is a brilliant, sneering slice of baroque pop, driven by Brian Jones’ marimba and a chugging organ. It’s effective, cynical, and cool. But Andrew Loog Oldham, the impresario behind Immediate Records, heard something else in it entirely. He heard a cathedral.

Oldham’s vision for Immediate was to create “pop art,” elevating singles into cinematic statements. He saw Farlowe, the raw, North London R&B shouter, as his secret weapon. And in Jagger’s acerbic put-down of a fading socialite, Oldham and Jagger saw the blueprint for a monument. They weren’t just covering a song; they were rebuilding it from the foundations up, swapping garage rock grit for symphonic grandeur.

What they created is one of the defining records of its time, a perfectly executed collision of raw soul and sophisticated orchestration. It begins not with a bang, but with a question. The delicate, almost playful notes of a xylophone or marimba dance into the space, a sound so distinctive it’s instantly recognizable. It’s a deceptively light opening, a musical curtsy before the curtain is violently torn aside.

Then, the orchestra enters. Not tentatively, but as a wave of sound. Arranger Arthur Greenslade didn’t just add strings; he weaponized them. They swell with dramatic intent, creating a bed of tension that underpins the entire track. The rhythm section lands with a confident thud, locking into a groove that is both powerful and impeccably stylish. It’s the sound of Swinging London in its absolute pomp: bold, expensive, and utterly sure of itself.

This piece of music is a masterclass in dynamics. The arrangement breathes. Brass sections stab through the mix like flashes of paparazzi bulbs, accenting the end of a vocal line. A subtle but insistent piano provides rhythmic support, almost hidden beneath the orchestral layers but essential to the forward momentum. Every element has its place, meticulously positioned in the sonic landscape to serve the song’s central drama.

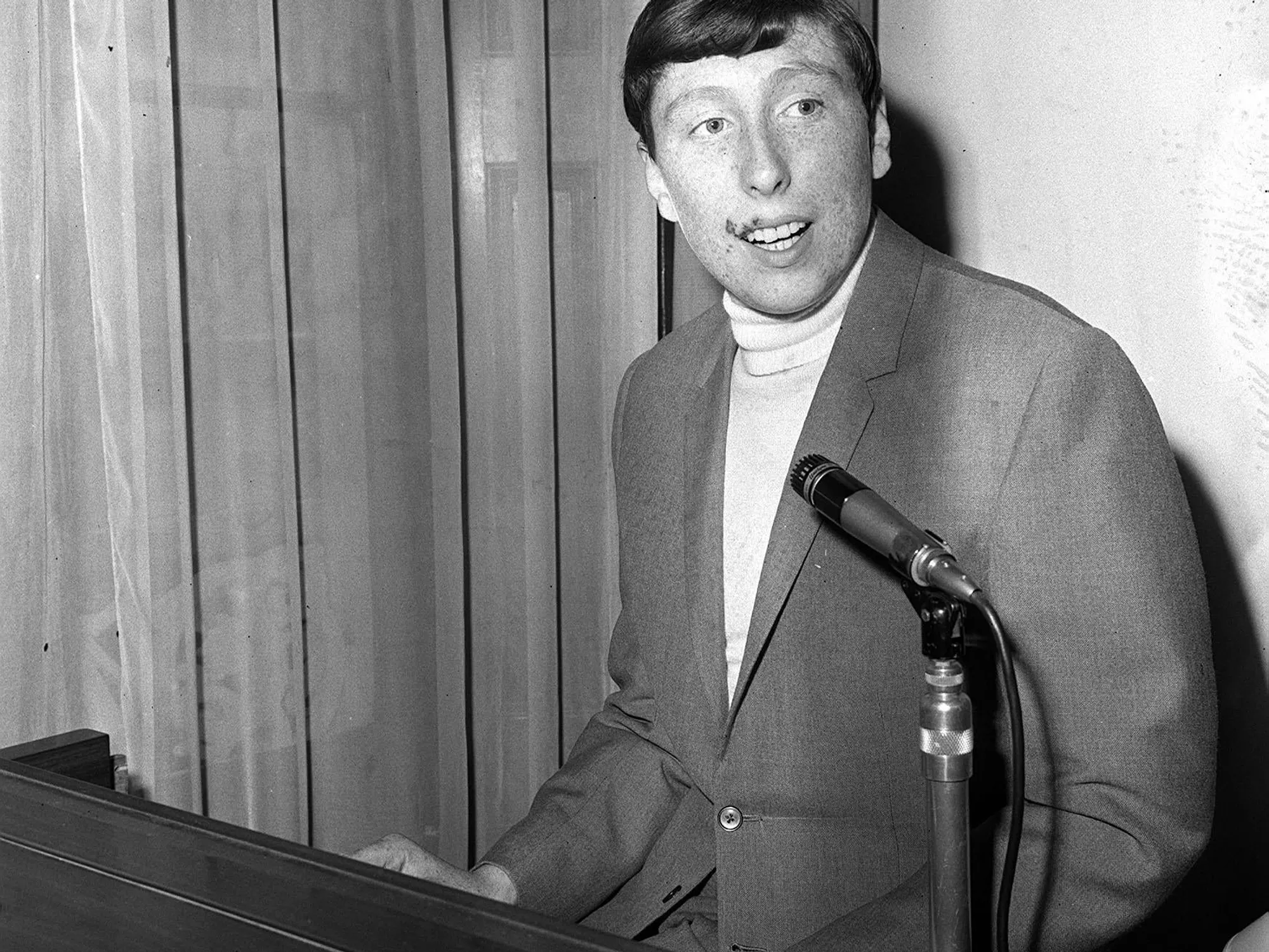

And at the heart of that drama is Farlowe. When he opens his mouth, the polished veneer of the production is electrified by pure, uncut humanity. His voice is a magnificent instrument, full of bluesy grain and capable of astonishing power. He isn’t merely singing the lyrics; he is inhabiting them, sneering them, grieving them. You believe every word of the condescending kiss-off because he sells it with such conviction.

“You’re obsolete, my baby,” he declares, and the judgment is absolute. There is no pity in his delivery, only the cold finality of a door being slammed shut. He stretches syllables, his vibrato trembling with a mixture of rage and release. He is the working-class voice of authenticity delivering a verdict on the ephemeral world of fashion and high society.

“It’s the sound of a bluesman fronting a symphony, a voice of raw earth standing defiant against a sky of silken strings.”

Consider the journey of listening. Through a small transistor radio in 1966, it must have sounded colossal, a transmission from another, more glamorous world. Today, experienced through a pair of proper studio headphones or a high-fidelity home audio system, its genius is even more apparent. You can hear the subtle scrape of the bow on the cello, the faint echo on the brass, the sheer scale of the room it was recorded in. The production isn’t just big; it’s deep.

The song captures a universal, albeit uncomfortable, moment. We have all, at some point, felt the ground shift beneath us. The culture moves on, the party ends, and the clothes that once felt like a uniform of belonging suddenly look like a costume. The song’s protagonist is being told she is no longer relevant, a brutal but perennial human fear. Farlowe’s version captures the cruelty of that moment, but its triumphant sound also offers a strange form of empowerment, the thrill of being the one to walk away.

This is why the record endures. It’s more than a time capsule. It’s a perfectly constructed emotional drama, told in under four minutes. The Stones’ original is a sharp-witted sketch; Farlowe’s is the full oil painting, complete with a gilded frame. The session musicians, the legendary arranger, the visionary producer, and the once-in-a-generation vocalist all aligned. It’s the kind of lightning in a bottle that defines a career and an era. It secured Farlowe his only number-one hit and gave the Jagger-Richards songwriting partnership one of its most glorious, if unconventional, triumphs.

To listen to “Out Of Time” is to be reminded of the sheer, audacious ambition of 1960s pop music. It’s a call to listen closer, to appreciate the craft, and to feel the raw, undeniable power of a human voice unleashed. It hasn’t aged a day; it simply waits, timeless and magnificent, for the next listener to be floored by its power.

Listening Recommendations

If you appreciate the grand, soulful drama of Chris Farlowe’s “Out Of Time,” you might explore these sonic relatives:

- The Walker Brothers – “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore”: For its equally epic, wall-of-sound production and a lead vocal performance brimming with romantic tragedy.

- Dusty Springfield – “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me”: A masterclass in building emotional tension, pairing a powerhouse soul vocal with a vast, dramatic arrangement.

- P.P. Arnold – “The First Cut Is the Deepest”: Another Immediate Records classic, blending raw, soulful American vocals with a sophisticated British pop sensibility.

- The Righteous Brothers – “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'”: The blueprint for cinematic pop, showcasing a similar dynamic range from quiet intimacy to a towering chorus.

- Scott Walker – “Jackie”: For a more theatrical and surreal take on orchestral pop, but with the same commitment to a huge, all-encompassing sound.

- The Rolling Stones – “As Tears Go By”: The other side of the coin, showing the Stones’ own early forays into baroque, string-laden pop with a gentle, melancholic touch.