The tape seems to warm before the first line lands, like a lamp clicked on in a dark room. Then Conway Twitty’s baritone fills the space—close, unhurried, and hospitable, as if he’s pulling up a chair you didn’t know you needed. “I’d Love to Lay You Down,” released in 1980 at the dawn of a new decade for country radio, is one of those records that seems to inhale and exhale at human scale. It’s not a show of force. It doesn’t need to be. It’s a demonstration of presence.

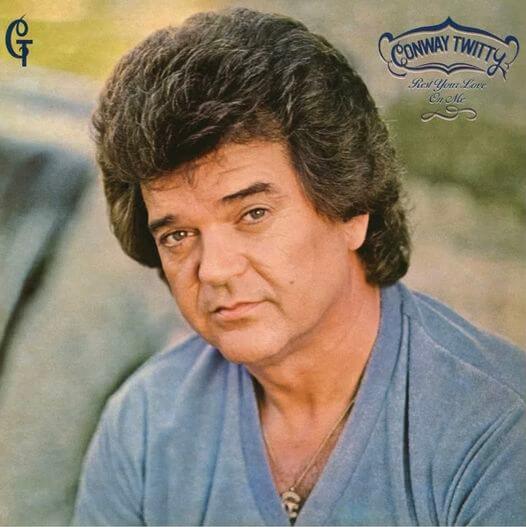

By 1980 Twitty was a fully established institution, long past the novelty of his early rock-leaning years and deep into his reign as a chart fixture on MCA Records. The song was issued as a single and included that same year on Heart & Soul, a fitting title for a period when he had both in abundant supply. Many sources note that producer Ron Chancey guided Twitty through these MCA years, and even if you listen blind to the credit line, you can hear the judicious hand: rounded edges, high polish, and a radio-ready silhouette that never sandpapers away the grain of the voice.

That voice is the lodestar. Twitty’s phrasing here is so natural it can be easy to underestimate; he front-loads clauses and then lets them drift, stopping a beat short of sentimentality. There’s confidence in the restraint. He lingers on vowels just long enough to carry warmth, not so long that they curdle into indulgence. Country ballads walk that tightrope all the time; Twitty turns it into a leisurely stroll.

The arrangement supports him with the grace of a well-drilled ensemble at its kindest. A muted rhythm section lays down a slow sway that feels like late evening—a tempo that suggests the day has already done its talking. Soft pads from the strings float in like curtains moving with a window cracked, while the steel accents arrive as glimmers rather than streaks. You can hear how the engineers built a pocket around the baritone: the reverb never shouts; it breathes. If you lean in, you catch the decay of a tail on a snare brush, the small shimmer of a cymbal, the hush of a room that welcomes intimacy instead of spectacle.

This is countrypolitan design, yes, but the tailored suit fits. Where some arrangements of the era hardened into lacquer, this one still moves. A single line of harmony vocal opens the horizon slightly on the chorus, giving Twitty’s declarative center a halo. One neatly voiced keyboard figure, maybe an electric variant or a subdued acoustic, traces the chord bed with touches that register less as notes and more as the nudge of reassurance. Just once, a brief flourish from the steel reminds you that tenderness can have a cutting edge.

There’s a subtle drama to how the instruments take turns. The bass is discreet but articulate, pushing the melody forward in half-steps that feel like small admissions. The drums are a model of tact. They do not chase fills; they escort the singer. And then there’s the moment when a lightly picked figure surfaces—just a bar or two—offering a contour line that tucks itself away again. In a record about closeness, these gestures act like eye contact: not constant, but decisive.

It is worth pausing on the lyric stance. Love songs can posture, can overreach, can declare more than they can carry. Twitty’s tone doesn’t bargain or boast. It attends. The title might promise a grand seduction, but the record itself is informed by care—an awareness of the beloved’s day, the weight of routine, the restorative power of simple touch. For all the attention this song has received as a country bedroom classic, it’s really a portrait of privacy. Where a thousand pop singles raise the stakes into melodrama, this one lowers the lights into trust.

From a career vantage, “I’d Love to Lay You Down” exemplifies Twitty’s late-’70s to early-’80s swath of No. 1 country singles, a stretch of extraordinary consistency that allowed him to refine what he did best. He had already traversed multiple stylistic rooms—teen idol, crossover artist, Nashville stalwart—and by the time this single appeared, he was building a catalog of gently authoritative ballads. The charts agreed, and while exact week counts are not the point here, the record’s high placement affirmed that Twitty’s soft-spoken approach could still command the airwaves in a moment when the format was negotiating its own crossroads.

The production, reportedly under Chancey’s steady supervision, feels purpose-built for radio without sacrificing hospitality for the living room. If you’ve ever pulled this track up on a good pair of studio headphones, you know how the baritone sits just forward of the strings, how the steel is panned with just enough width to suggest space without dispersing focus. It’s the sound of a team remembering that country music’s power thrives in midrange truths rather than treble fireworks.

I like to think of this cut in three scenes. First: a late-night drive on a two-lane road outside a small town. The local DJ back-announces a dancehall favorite, then rolls into Twitty, and the car’s cabin feels a size larger. The song arrives not as a seduction but as a kindness that once again makes solitude optional. You glance at the right lane’s reflective markers as they pass, each one a little heartbeat. The chorus hums along at a volume you’d call inside voice.

Second: a kitchen on a Sunday evening. The dishes are done, the sink is clean, and the last light is throwing rectangles on the table. Someone in the next room is folding laundry, and on the speaker you’ve set low the record begins. The steel murmurs; the strings soften the corners. For a few minutes, the domestic becomes cinematic. The promise embedded in the title becomes less about pillows and more about rest—how a body relaxes when it believes it can.

Third: a wedding reception where couples from three generations share the floor. A grandfather who danced to this song when it was new teaches a granddaughter the small sway that fits it. They don’t say anything. They don’t need to. The record belongs to them in equal measure for exactly four minutes of time travel.

As a piece of music, the track demonstrates how spareness can feel abundant when every element is placed with care. The line between sentiment and sentimentality is thin; Twitty keeps to the right side by focusing on specifics: small displays of affection, everyday gestures, the junior details of adoration that, taken together, become a life. The song carries no narrative twist and no dramatic turn. Its twist is how often listeners find their own lives in it.

You can hear why it endured across formats. In an era when rock was hardening and pop was brightening, this single chose warmth and stayed there. It does not dazzle; it persuades. It does not climb; it settles. You can tuck it into a quiet evening and it will tint the entire hour with its palette.

A footnote for context: songwriter Johnny McRae penned the tune, and Twitty’s reading helped crystallize its reputation. Twitty had long since proven that he could carry tempo and swagger. What he does here is more impressive: keeping attention in the small zone where a listener meets a human voice and decides to trust it.

Notice how the vocal sits at the front edge of the beat but never presses it. That small rhythmic posture invites the band to lean back while the lyric leans forward. The result is a slow tide. Across the second verse the strings become more audible, then recede; the steel’s harmonics bloom and then vanish; the background vocals touch the edges of the frame and quickly let go. There’s a drafting discipline to this mix. You might not clock the arrangement changes in real time, but your breathing adjusts to them.

On systems with good dynamic range—be it a living-room rig or a respectable car stereo—the song’s low-level details come alive: the breath before a phrase, the hush at the end of a line, the comfortable seal around the low mids. It’s friendly to modest speakers and better still on careful setups, the kind associated with home audio that prioritizes warmth over brute force. A piano enters delicately in the third act of the track, offering soft root motion that thickens the floor beneath the voice without daring to call attention to itself.

The most telling quality is the record’s emotional geometry. Instead of stacking feelings vertically—higher notes, bigger drums, brighter strings—the performance widens them horizontally. Each repetition returns with a slightly different angle: more fondness here, more patience there. This is how long partnerships sound when sung.

“Intimacy rarely arrives with a fanfare; it walks in quietly and decides to stay.”

Culturally, the song’s longevity isn’t just about nostalgia. It’s about the fantasy of a world where tenderness is fluent, where attention is the first language. Plenty of hits promise wildness; fewer promise rest without retreat. In a century that keeps accelerating, this promise hasn’t lost value.

Placed in Twitty’s career arc, the single affirmed something both the artist and his audience already knew: his gift wasn’t only in turning heads; it was in lowering shoulders. He could do the rhinestone glare on television and the gentleman’s hush on record, and here he chooses the latter with assurance. The cut reinforced his standing as a balladeer whose power gathers in the quiet.

And as production trends swing back around every few years, you can hear modern country singers reaching for this same equilibrium: polish that honors grain, arrangements that glow rather than shine, choruses that lift without levitating. “I’d Love to Lay You Down” stands as a blueprint for how to sound grown, not merely polished; how to sound tender, not merely soft.

One practical note for collectors and listeners diving deeper into Twitty’s catalog: this track sits beautifully alongside his other early-’80s ballads, and its appearance on Heart & Soul gives it a center spot in that sequence. Spin it next to his late-’70s work and you’ll feel the arc—more velvet, more patience, a deeper attention to the domestic sublime.

It’s telling that the record works at different volumes. On a whispery late-night listen, its small decisions come forward: the brushed percussion, the steel’s careful entrances. On a brighter daytime pass, the melody’s generosity carries you. This duality—the ability to score both quiet and company—helps explain why the song still feels like a friend.

Some will come to it for romance, some for memory. I come back for craft. Songs that live this long rarely do so by accident. There is architecture beneath the tenderness: lines that fit the mouth, a range that flatters the voice, a band that knows when to speak and when to disappear. You could imagine the session unfolding with minimal drama, the kind of recording day where competence and calm produce glory.

For those who study arrangements, it’s a gentle masterclass. Strings and steel coexist without crowding. The vocal stack is restrained. The rhythm section is conversational rather than declarative. The overall temperature remains warm, but not humid. If you were transcribing it for sheet music, you’d find a modest chord vocabulary elevated by voicing choices that keep everything supple.

I grew up hearing this song on radios that whispered from kitchen counters. Coming back to it now, I’m struck by how it doesn’t age; it simply returns. Not every classic has that grace. Some grow smaller with time as their tricks become familiar. This one grows nearer. It describes a kind of care that keeps revealing new rooms as life does.

In the end, “I’d Love to Lay You Down” earns its place not by conquest, but by consent. It doesn’t push you into feeling; it makes room for feeling to step forward. That is a rare distinction. It’s the reason the title line, spoken softly, still feels like a promise kept.

If you revisit the track after a spell, take a moment for the basics—how the vocal sits, how the steel eases, how the strings breathe, how a single guitar figure can change your posture for a measure and then vanish. This is not a song that lives on surprise. It lives on recognition, on the delicate courage of saying what matters plainly and beautifully. And it still does.

Listening Recommendations

-

George Jones – He Stopped Loving Her Today: A 1980 benchmark ballad whose spare arrangement and baritone gravity mirror Twitty’s patient storytelling.

-

Charlie Rich – Behind Closed Doors: Countrypolitan warmth with strings and satin rhythm, a natural companion in mood and polish.

-

George Strait – You Look So Good in Love: Early-’80s elegance and gentle tempo, built around restraint rather than flash.

-

Conway Twitty – I May Never Get to Heaven: Another Twitty slow-burn where his voice carries everyday devotion with unfussy grace.

-

Ronnie Milsap – It Was Almost Like a Song: Piano-centered romance from the same broad era, luxuriating in soft-focus arrangement.

-

Alabama – Love in the First Degree: Smooth early-’80s country with pop sheen, trading in warmth and easy melody rather than bluster.