There is a moment, late in the evening on a long drive, when the interstate begins to feel less like concrete and steel and more like a river. The passing lights blur into impressionistic streaks of color, and the radio, tuned low, becomes the only witness to your solitude. It is in that space—the transition between action and reflection—that the best outlaw country music lives. And few recordings capture that restless, elegiac spirit quite like The Highwaymen’s collective rendition of “Me and Bobby McGee.”

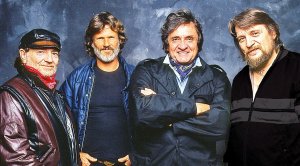

This is not the electric, heart-shattering catharsis of Janis Joplin. It is not the original, jaunty country-pop hit for Roger Miller. This piece of music, delivered by the genre’s most formidable quartet—Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and the song’s architect, Kris Kristofferson—is something quieter, heavier, and ultimately, far more profound. It is a shared memory whispered around a campfire, a confession traded between four men who had already lived ten lifetimes on the road.

The Context: Four Corners of the Outlaw Era

To truly appreciate this version, we must first place it within the context of The Highwaymen’s career. The supergroup itself was a phenomenon born of friendship, mutual respect, and a shared label (Columbia, for their early works) that saw the commercial potential in gathering these titans of “outlaw country.” This particular recording, while a foundational track for Kristofferson, was frequently included in the group’s live shows and appears on various compilations, cementing its status as a core part of their collaborative repertoire.

In essence, The Highwaymen were a late-career victory lap, a statement by the four artists who had defined the rugged, anti-Nashville sound of the 1970s. Their 1985 self-titled debut album, Highwayman, had resurrected all four careers on the charts, fueled by the Jimmy Webb-penned title track. “Me and Bobby McGee,” already a decades-old classic, served as a natural inclusion. It was Kristofferson’s signature song, a foundational text of their entire movement. When he sings the line, “Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose,” it is not a bohemian musing; it is the collective philosophy of four legends who had already lost and gained everything.

Sound and Instrumentation: The Bare Essentials

The arrangement is sparse, built primarily on the interlocking rhythm section and two iconic voices of the guitar. There is a clean, almost antiseptic quality to the recording, likely captured in a later-era studio environment that favored clarity over the warm, analog saturation of their earlier work. The core tempo is a loping, road-weary shuffle, slower than most definitive covers, giving the words time to hang in the air.

The instrumentation is a masterclass in restraint. There is no heavy piano or sweeping string arrangement here. Willie Nelson’s distinctive, nylon-string guitar, Trigger, often takes the lead on melody, its worn-in timbre providing a delicate, fingerpicked counterpoint to the deep, resonant strumming of the rhythm guitar (likely from Jennings or Cash, often played with a heavier hand). The mix focuses ruthlessly on the vocal interplay.

The vocals are, naturally, the heart of the matter. The story is divvied up between the four outlaws, each trading verses, lending the narrative an extraordinary dramatic tension. Cash, with his bass-baritone rumble, delivers the most world-weary lines; Jennings’ voice has that trademark metallic sneer, the sound of a man who knows exactly what it means to be “busted flat in Baton Rouge.” Nelson’s plaintive, high-lonesome tone floats over the chorus like the dust kicked up by the diesel rig they thumbed down.

Kristofferson, the songwriter, takes the lead on the final, devastating verses. His voice, never conventionally polished, now carries the full weight of years and experience. When he hits that final verse about the loss of Bobby, his phrasing is less a soaring cry and more a simple, inescapable fact. The absence of overproduction allows the natural vibrato and subtle grit in each man’s vocal texture to be felt, lending the track the kind of raw authenticity often sought by people investing in premium audio equipment for their listening rooms. The entire performance feels less like a recorded session and more like a moment frozen in time.

Anatomy of Regret: Thematic Resonance

The power of “Me and Bobby McGee” has always resided in its perfect duality: the exhilarating promise of absolute freedom juxtaposed against the crushing weight of its aftermath. Nothing left to lose becomes a mantra, a terrifying but seductive philosophy. When this quartet sings it, the stakes feel dramatically higher.

In their youth, this song was about leaving. In their middle age, it became about staying. For Cash, Jennings, Nelson, and Kristofferson, who had collectively grappled with addiction, failed marriages, and the pressures of superstardom, the road was both sanctuary and prison. Their version finds the regret that lurks beneath the surface of the wanderlust. The feeling good was easy when Bobby sang the blues, but the simplicity of that life is what was traded for fame, for fortune, for permanence—and the sting of the trade-off is audible in the worn cracks of their voices.

This particular arrangement uses silence and space as instruments. There are pregnant pauses between Willie’s light lead guitar flourishes and the next vocal entrance. The mix is wide and dry, giving the impression of an acoustic performance captured in a large room, perhaps an empty auditorium after the crowd has gone home. This sonic landscape perfectly frames the song’s central theme: the echo of a profound, life-altering absence.

“This is not a celebration of the open road; it is a eulogy for the uncomplicated past, delivered by four men who understand that freedom’s ultimate price is having nobody left to share it with.”

I recall once driving through the Texas Hill Country, not far from where Kristofferson began his journey, listening to this very version. It was a humid afternoon, and the light filtering through the dust-caked windshield made the landscape appear sepia-toned. The song wasn’t just on the radio; it was part of the atmosphere. That’s the magic of The Highwaymen—they didn’t just cover a song; they absorbed it into the mythos of the American West, turning it into a final, definitive meditation on the kind of love that can’t be caged by asphalt or a career arc. It’s a mandatory listen for anyone who gives or takes guitar lessons rooted in country and folk stylings, showcasing how much story can be told through simple, clear strumming patterns.

This rendition will likely never eclipse Joplin’s iconic scream or Kristofferson’s own earnest original, but it stands as the most authoritative country reading of the lyric. It’s the final word from the outlaws, a testament to the enduring genius of Kristofferson’s pen, and a sobering reminder that every adventure eventually ends in a quiet goodbye.

Listening Recommendations

- Willie Nelson – “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”: Another sparse, essential country track that uses vocal vulnerability and a simple acoustic arrangement to convey devastating loss.

- Johnny Cash – “The Man Comes Around”: For the deep, gravelly final-act vocal delivery and apocalyptic gravitas that Cash brings to the Highwaymen’s texture.

- Waylon Jennings – “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)”: Shares the theme of trading a complicated, modern life for a simple, romanticized past on the road.

- Kris Kristofferson – “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”: A sister song of the same era, detailing the stark, lonely reality that follows a night of transient, easy freedom.

- Grateful Dead – “Box of Rain”: Features a similarly contemplative, road-weary theme of looking back and accepting fate with quiet, folk-rock resignation.

- Bob Dylan – “Tangled Up in Blue”: A long-form, narrative folk piece of music that masterfully jumps across time and location, focusing on a relationship defined by constant motion and separation.

Video

Lyrics