Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Born on the Bayou” opens the 1969 album Bayou Country with a slow-boiling swagger that helped define the band’s mythic “swamp rock” signature. From its first chiming, tremolo-soaked guitar figure to John Fogerty’s searing vocal, the track conjures a humid, moonlit American South that most listeners know only from novels and folklore. In the CCR canon it occupies a special place: less a radio single than a mood, an atmosphere, a world you can step into—mosquito-heavy air, dark water, and the distant thump of a Saturday-night dance across the levee.

The album context: Bayou Country and CCR’s breakout year

Bayou Country was CCR’s second studio release and the first of three albums the group issued in 1969, a creative sprint virtually unmatched in classic rock. If Green River would later refine the formula and Willy and the Poor Boys would broaden it, Bayou Country established it: lean arrangements, unfussy production, and a tactile sense of place. The record contains “Proud Mary,” the band’s best-known song, but it is “Born on the Bayou” that sets the aesthetic stakes. Sequenced first, it functions like a prologue, a musical map legend that tells you what kind of terrain you’re entering.

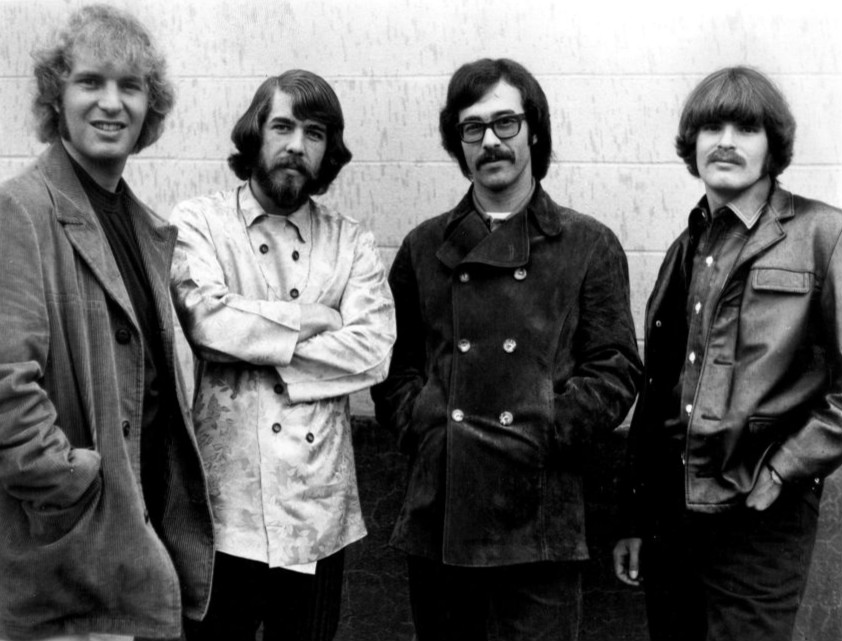

The album’s overall sound is economical. CCR never crowded their mixes with lavish ornamentation or orchestration; instead, they relied on the chemistry of four players in a room. John Fogerty’s writing and production emphasize clarity—every element feels audible, necessary, and in service of the groove. Bayou Country is also a study in contrast: the easy, rolling “Proud Mary”; the gritty “Bootleg”; the nocturnal sprawl of “Graveyard Train”; and the extended rave-up “Keep On Chooglin’.” “Born on the Bayou,” with its simmer rather than sprint, teaches you how to listen to the record—attentively, at ground level, where the beat feels like it’s moving through damp earth.

Instruments and the architecture of the sound

At its core, “Born on the Bayou” is a masterclass in restraint and texture. The instrumentation is CCR’s classic quartet: two guitars, electric bass, and drums. Tom Fogerty’s rhythm guitar locks into a hypnotic strum, acting like the bayou’s tide—steady, unstoppable—while John Fogerty’s lead guitar paints the shoreline with ripples of tremolo and subtle bends. The tremolo effect, likely from a tube amplifier’s onboard circuit, gives the primary riff its pulse—an undulation that feels organic, like light reflecting off black water. You don’t hear a forest of overdubs; you hear electricity breathing.

Stu Cook’s bass underlines the tonic with minimal movement, creating a cushion that lets the guitars breathe and the vocal cut. His lines play the space between drums and guitar rather than populating every measure with fills. Doug Clifford’s drumming is similarly unadorned yet deeply musical: a solid snare backbeat, careful hi-hat work, and tom accents that bloom like distant thunder. The kit sounds present, not hyper-compressed, giving the groove a live, room-air presence that modern productions sometimes chase with plug-ins.

The main guitar riff is built around blues pentatonic shapes, but the phrasing, micro-slides, and sustained notes are what make it feel swampy rather than urban. The rhythm is straight, not a shuffle, yet there’s a lilt in the interplay—a pocket that suggests humidity and patience. Fogerty’s lead tone occupies that sweet border between clean and overdriven; you can hear picks against strings and the grain of the amp’s speakers. There’s no obvious keyboard, horn, or auxiliary percussion; the song achieves its atmosphere with four instruments and a voice, a testament to the band’s discipline.

For listeners new to rock-crit vocabulary, think of the essential building blocks—piece of music, album, guitar, piano—simple words that describe simple tools. CCR proves that with the right touch, those tools can feel elemental, like wind and water.

The voice that sells the myth

If the instruments supply the swamp, John Fogerty’s vocal supplies the ghost story. Part of the enduring fascination with “Born on the Bayou” is how convincingly Fogerty inhabits a place he did not grow up in. He leans into a Southern inflection without caricature, favoring long, vowel-heavy lines that travel like heat haze. His delivery is equal parts sermon and field holler—front-porch storytelling pitched to reach the back fence. Crucially, he never oversings. The grit in his upper-register wails functions as a color in the arrangement; even when he snarls “chasin’ down a hoodoo there,” it’s musical as much as textual.

Lyrics: Hoodoo, memory, and the geography of longing

“Born on the Bayou” isn’t an autobiographical postcard; it’s an act of imaginative memory. The images—Fourth of July fireworks, bullfrogs calling, a childhood spent in the backwoods—compose a homesick prayer to a place that feels both specific and archetypal. The famous “hoodoo” line places the song in a folk-magic landscape where superstition and story overlap. Fogerty weaves nostalgia without sentimentality; the childhood he remembers is not sanitized. There are cops, there’s trouble, there’s the sense of a world bigger than any one kid can fully understand.

That tension—between the innocence of remembered summers and the darker realities implied by “hoodoo” and pursuit—gives the song its dramatic contour. You could imagine a more ornate writer stacking metaphors; Fogerty uses nouns and verbs you can hold in your hand: runnin’, backwood, bullfrog, bayou. The words are percussive and tactile, matched to a music that feels carved rather than painted.

Arrangement: the power of patience

Technically, very little “happens” in “Born on the Bayou” by way of sectional fireworks. That’s not a deficiency; it’s the point. The track teaches patience. The intro establishes the tremolo figure, the band enters with sturdy minimalism, and then the verses and choruses alternate like call and response. Dynamic builds are achieved mostly by the vocal intensity and subtle expansions in the drum and rhythm-guitar patterns. In the bridge and instrumental interludes, the lead guitar rides the prevailing current rather than announcing itself as a separate showpiece. In a decade known for ambitious studio epics, CCR found drama in endurance.

This arrangement also explains why the song became a set-opening favorite in concert: its groove is a fuse. Light it, and a crowd is suddenly in the same room, breathing at the same tempo. It is no accident that the band leaned on it for major appearances; the tune’s hypnotic steadiness recalibrates an audience’s nervous system and says, quietly but firmly, “This is the night we’re going to have.”

Production: space, air, and the honesty of four tracks

“Born on the Bayou” sounds like a band playing in a room because that is, essentially, what it is. You can sense microphone distance—the sound of cymbals reaching the air around them, the way guitar speakers interact with a wall. Reverb is present but judicious, likely plate-style on the vocal for sustain and a halo. The guitars sit left-right with a center that never feels hollow; the bass and kick anchor that center while the snare provides articulation. Nothing feels “fixed” in the modern sense. It’s performance captured, not performance perfected after the fact.

That production philosophy complements the lyric. You can’t convincingly sing about backwoods and levees while a dozen invisible overdubs tell listeners they’re inside a laboratory. CCR’s brand of authenticity doesn’t come from absolute fidelity to a geographic fact; it comes from musical choices that honor the feel they’re invoking.

Relationship to “Proud Mary” and the rest of Bayou Country

One of the sly pleasures of Bayou Country is how “Born on the Bayou” reframes “Proud Mary.” Heard out of context, the latter reads as a jaunty, riverboat-ready singalong—sleek, almost urbane in its phrasing. But when it arrives after “Born on the Bayou,” “Proud Mary” becomes a daylight travel song preceded by nocturnal legend. You’ve just emerged from the cypress trees into open water; the wheel spins, and the sky lifts. That dynamic owes everything to sequencing. Meanwhile, deeper cuts like “Graveyard Train” extend the swamp mood into a kind of trance blues, while “Keep On Chooglin’” taps dance-hall energy. The album isn’t monochrome; it is a palette arranged around one dominant color: dark green.

Influence, genre, and the fiction that tells truth

By calling what CCR did “swamp rock,” critics risk making it sound like a subgenre curio, the preserve of bayou natives playing zydeco-adjacent jams in humid bars. But “Born on the Bayou” demonstrates something larger. Fogerty’s imagination created a place where American blues, rockabilly, and country intersect in a single, cohesive mood. The song’s DNA is just as connected to Delta blues phrasings and Sun Records simplicity as it is to any regional folk style. In that sense, it foreshadows the Americana movement: writers and bands seeking a unified roots grammar, less about authenticity as passport and more about authenticity as intention.

Crucially, the track also shows how fiction can tell emotional truth. Fogerty was not documenting a census tract; he was inventing a stage upon which real feelings—loss, desire, memory—could play out. Listeners recognize the truth because the details are right and the music feels lived in. That’s why “Born on the Bayou” still resonates with audiences who have never stood within a hundred miles of Louisiana wetlands.

Practical listening notes (and why the groove still works today)

Because the arrangement is so spare, small playback choices matter. On good speakers or headphones you’ll hear the tremolo’s pulse as a separate organism, like a moth flitting around a porch light. The bass’s roundness becomes more obvious, and the cymbals’ decay adds breath between phrases. For musicians learning the song, resist the urge to fill; the space is your friend. Guitarists often discover that the hardest thing here is not the riff but the discipline to stay inside it, to dig deeper rather than reach for flash. If you’re exploring roots styles yourself and considering guitar lessons online, this track is an excellent case study in tone, muting, and pocket—areas that matter as much as scale runs.

The song also has practical implications for creators and curators. Because the vibe is so vivid, it scores well for film and television scenes requiring dusky mystery or road-night solitude—a reason it frequently enters conversations in music licensing. Its tempo avoids chase clichés while still conveying motion. Put it under a slow pan of headlights floating past cypress trunks and the image instantly acquires narrative.

Why the lyric matters as much as the riff

It’s tempting to reduce “Born on the Bayou” to its guitar atmosphere, but the lyric’s diction does as much heavy lifting. “Hoodoo” isn’t just a colorful noun; it implicates a whole folk-religion matrix, hinting at forces beyond the narrator’s control. Lines about Fourth of July fireworks and bullfrogs refuse heightened metaphor and choose tactile memory—fireworks pop, bullfrogs croak, and the sound is both celebration and omen. The entire text behaves like an incantation: simple, repeated phrases that accumulate power through cadence.

Legacy: a lantern that still burns

In the decades since its release, “Born on the Bayou” has become a shorthand for a feeling: cinematic, earthy, half-dangerous. Newer roots and Southern-rock acts borrow its blueprint—open with a hypnotic guitar figure, let the rhythm section set a throb, and place a commanding voice on top—but few capture the same chiaroscuro of menace and longing. Part of the song’s durability is that it sounds like no particular year; it’s too elemental to age. Spin it next to a modern Americana track, and it will neither feel quaint nor overbearing. It simply is.

For collectors, Bayou Country remains a rewarding listen on any format; if you’re the sort who loves to compare pressings or buy vinyl records online, the album’s uncluttered production often yields clear differences between cuts, giving you a personal window into how mastering choices accentuate bass bloom or tremolo shimmer. For casual listeners, a well-mastered digital version will still deliver the viscous mood that made the track a stage-lighting tool for CCR’s live sets.

Recommendations: if you love “Born on the Bayou,” try these

To stay in the same humid atmosphere, try CCR’s “Green River,” which tightens the swamp mood into a driving, radio-ready jewel. “Run Through the Jungle” takes the darkness further, adding menace and a thicker guitar cloud. From outside the CCR catalog, Tony Joe White’s “Polk Salad Annie” shares the same regionally vivid storytelling and low-slung pocket. The Band’s “Up on Cripple Creek” isn’t swamp rock per se, but its funky, earthy pulse and Americana imagery rhyme with CCR’s sense of place. Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Swamp Music” plays like a more boisterous cousin. And for another CCR deep cut that pairs nicely, “Keep On Chooglin’” turns the bayou into a barn-burning jam.

Final thoughts

“Born on the Bayou” succeeds because it’s immersive without being busy, evocative without leaning on studio trickery, and rooted without being provincial. It opens Bayou Country like a curtain draw, announcing that CCR’s America is an imaginative landscape where blues toughness, country straightforwardness, and rock propulsion meet. The band trusts a small set of tools—voice, guitars, bass, drums—and extracts from them a language that feels as inevitable as weather. In an era when we often equate greatness with accumulation, CCR reminds us that restraint can also sound like power.

Return to the track today and it hums with the same voltage. Step into that first tremolo throb and you’re already knee-deep in water up to your shins, hearing a bullfrog somewhere in the dark. The story might be invented, but the feeling is real—one of those rare records that turns the ordinary room you’re sitting in into a place you’ve never been and somehow remember. That is the quiet magic of this classic cut and of Bayou Country as a whole: once you enter, you can smell the wood smoke, hear the insects, and, for four and a half minutes, belong to a different night entirely.