Introduction: A road-weary postcard from the American West

“Lodi” is one of those rare songs that transforms a dot on the map into a feeling you can carry around. Written and sung by John Fogerty and released in 1969, the number distills the twilight hour of a working musician’s life—when the set is done, the cash is light, the bus is late, and the bar’s neon hum outlasts the applause. The refrain—brief, rueful, unforgettable—makes the California town stand for every waystation where dreams idle just long enough to sting. As storytelling, it’s impeccably economical; as roots-rock craft, it’s a master class in restraint. You don’t need a wall of sound to make a wallop. Creedence Clearwater Revival prove that here with a small combo, a clean mix, and melodies that feel carved from oak.

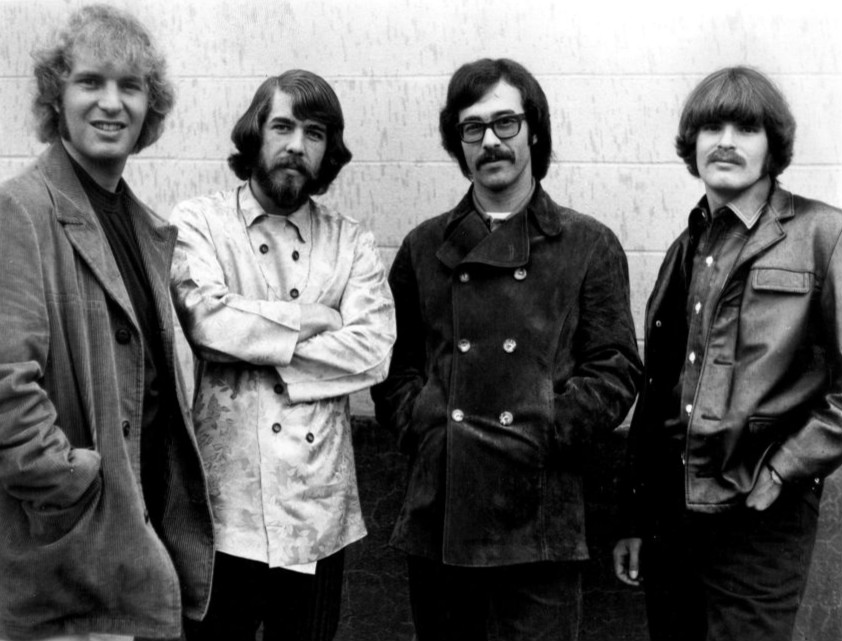

The album context: Green River and CCR at full stride

“Lodi” appears on Green River, the band’s second LP of 1969 and a landmark in the CCR catalogue. If the earlier Bayou Country established their swamp-rock mythology, Green River refined it into a taut sequence where every track earns its place. You get the title cut’s river-cooled swagger, the apocalyptic cheerfulness of “Bad Moon Rising,” the motorik churn of “Commotion,” the reflective “Wrote a Song for Everyone,” and, nestled among them, “Lodi” as the album’s plain-spoken heart. The record is lean—ten songs, no filler—and it sounds like a band that had figured out how to be timeless without being vague. Recorded quickly and with minimal overdubs, Green River is the document of a group playing as if the clock—and the touring schedule—were always ticking. In that context, “Lodi” functions as a thematic hinge: a postcard from the road slipped inside a set that’s otherwise full of motion.

What makes the album introduction especially relevant is that Green River balances three CCR personalities at once. There’s the barnstorming bar band (“Commotion”), the roots storytellers (“Lodi,” “Wrote a Song for Everyone”), and the hit machine (“Bad Moon Rising”). “Lodi,” with its modest tempo and reflective lyric, keeps the album human-scaled. It proves that grandeur can be intimate, too.

Arrangement & instruments: economy that sings

CCR’s arrangement choices define the song’s emotional climate. The instrumentation is famously sparse—guitars, bass, drums, and vocals—yet the parts interlock with clockmaker precision.

-

Rhythm guitars: A lightly overdriven rhythm guitar keeps the engine purring with a steady, almost folk-strum pattern. It’s neither flashy nor ornamental; it gives the syllables a shoulder to lean on and provides the harmonic skeleton.

-

Lead guitar: The lead voice glides with country-flavored, singable licks—tasteful bends, unhurried double-stops, and a tone that favors clarity over bite. You can hear the pickup switch set to “storytelling.”

-

Bass: Stu Cook’s bass part is a lesson in melodic economy. It contours the chord changes with just enough movement to suggest travel without arrival—a perfect mirror of the lyric.

-

Drums: Doug Clifford’s drumming is pocket-first. The snare is crisp, the kick conservative, cymbals restrained. No fills elbow the vocal out of the frame; the beat hangs back and makes space for the song’s sighs.

-

Vocals & harmony: Fogerty sings upfront and slightly dry, avoiding lush reverb that might soften the edges of the story. Occasional harmony support amplifies key phrases, but there’s never a choir—only a companion.

Because CCR kept their textures unvarnished, you can hear every decision. There’s no luxurious pad, no busy piano filigree, and no studio trick begging you to notice it; the group trusts the lyric and melody. The production’s clarity allows the guitar timbres to function like brushstrokes: clean, slightly twangy lines set against a supportive strum create a durable Americana palette. (For SEO clarity: fans who discover “Lodi” through modern music streaming services often comment on how timeless that palette still sounds.)

Harmony, melody, and form: familiar bricks, a new house

Harmonically, “Lodi” lives in the friendly neighborhood of diatonic chords. The progression revolves around a classic I–IV–V frame, with tasteful passing moves that color the verses’ resignation and the chorus’s resigned lift. This is strophic writing with judicious variation: verses unfold as tight narrative stanzas, the chorus lands like a sigh you’ve practiced for years, and a short instrumental break offers the listener a window to breathe. The melodic line sits in the middle register—singable by non-virtuosos, therefore perfect for the barroom setting the lyric evokes. That accessibility is not a concession; it’s a strategy. The tune feels inevitable after one listen, which is why the hook has survived five decades of jukeboxes and road trips.

Lyric craft: character in a few strokes

“Lodi” compresses a musician’s memoir into a handful of brush lines. We meet a narrator who gambled on momentum and lost it at the worst time, in the wrong place. Details—promises of representation that evaporate, gigs that pay in rumor rather than money, the eternal wait for a ride out—collect until the chorus sighs, “Oh Lord, stuck in Lodi again.” Nine syllables; a whole plot. Fogerty avoids cleverness that would undercut realism; he uses ordinary language that rings with specificity. The trick is empathy. This is not a self-mythologizing outlaw; it’s a working player with a suitcase full of hope and a pocket full of coins.

The writing also threads a needle between self-pity and stoicism. The storyteller sees the joke, even as he’s the punchline. That’s why listeners in any hustle—musicians, freelancers, traveling sales reps—hear themselves in the corners. It’s not just about a town; it’s about inertia, and about the fragile economics of art.

Vocal performance: the grain of the road

John Fogerty’s voice is famously elastic—capable of both raspy urgency and melodic warmth. On “Lodi” he chooses the latter without losing bite. His phrasing leans slightly behind the beat, like someone who has learned patience the hard way. When the chorus hits, he opens the throttle just enough to put a shine on the hook, then pulls back before the performance becomes catharsis. That restraint keeps the focus on the character rather than the singer. If other CCR hits sport the preacher’s fire, “Lodi” wears the bartender’s nod: sympathetic, wry, unflustered.

Production aesthetics: live-in-the-room honesty

Part of the song’s authority comes from CCR’s broader recording philosophy during this era: short sessions, few overdubs, sounds that an audience could recognize from the stage. The mix favors presence over polish; guitars are forward but not blistering, the bass is audible without being boomy, and the drums don’t chase the cymbal gloss that tempted many late-’60s records. You can imagine the band playing this in a modest club with a decent PA and sounding almost exactly like the record. That fidelity between studio and stage is not just a technical choice; it’s an ethical one. It tells the listener, “This is who we are. What you hear is the band.”

Country lineage and American geography

Though Creedence were a Bay Area band, “Lodi” speaks fluent country. The lyric’s straight talk, the tempo’s ease, and the guitar’s twang place it near the Bakersfield school’s unadorned candor. You can hear echoes of honky-tonk melancholy, but without barroom caricature. What’s beautiful is the geographic honesty: the song names a Central Valley town, and it sounds like the flatland sky at sundown—big, a little empty, and made for thinking. CCR never needed to cosplay the South to write American; Green River proves their map included river towns, oil roads, and agricultural corridors with equal empathy.

Why it endures: specificity as universality

“Lodi” lasts because it’s concrete. The story has stakes, the town has a name, the character has a job, and the band sounds like humans in a room. That specificity opens, counterintuitively, into universality. Anyone who’s ever chased a lead that didn’t pan out recognizes the waiting room feeling. The song also offers the right amount of ambiguity. We don’t know what happens after the chorus fades; we only know that the narrator will try again tomorrow. That open ending keeps the listener’s imagination busy.

It also helps that the composition is built for ordinary voices. In bars and living rooms, “Lodi” works. You can play it with two guitars and a shaker, or with a full band and a Hammond organ, and it still communicates. For players, the tune is a friendly sandbox where taste matters more than chops—precisely the kind of piece of music, album, guitar, piano fans love to discuss when they’re swapping set-list ideas or teaching a friend the changes.

Practical musicianship: what to listen for

A few details reveal themselves on close listening:

-

The pocket. Notice how the snare doesn’t crowd the vocal. Clifford leaves tiny bits of air before fills, which keeps the lyric intelligible.

-

Guitar dialogue. The rhythm and lead guitars converse rather than compete. The lead often answers the vocal with short phrases, as if finishing the singer’s thought.

-

Bass contour. Cook chooses the scenic route between anchors; his lines imply movement even when the chord stays put, a subtle way of dramatizing the narrator’s urge to leave.

-

Dynamic ceiling. The band rarely breaks above mezzo-forte. When intensity rises, it’s the singer and the hook doing the heavy lifting, not the faders.

For guitarists exploring tone, the song is a reminder that “clean” is not the enemy of “expressive.” A small tube amp, light compression, and gentle right-hand dynamics will get you most of the way there. If you’re a learner mapping out the part, this track is a perfect bridge between strumming and melodic fills—exactly the kind of piece that turns casual players into arrangers. (If you’re starting from scratch, structured guitar lessons online can help you internalize those pocket-friendly licks.)

On genre boundaries: folk, country, rock—same town, different streets

“Lodi” is rock by lineage, country by attitude, and folk by narrative economy. CCR treat genre as a toolkit, not a cage. That’s why the song slips easily into country sets, Americana playlists, and roots-rock anthologies. The band never leans on studio decoration to signal style; they let the writing and playing do it. It’s a valuable reminder that the border between forms is porous, and that authenticity often lives in the space where instruments, voices, and stories line up.

Pairings and listening recommendations

If “Lodi” resonates with you, the following tracks make natural companions, whether you’re building a road-dusk playlist or studying Americana songcraft:

-

The Band – “The Weight.” Another place-name narrative with a traveler’s burden and a chorus you’ll sing forever.

-

CCR – “Who’ll Stop the Rain.” From a later period, but it shares “Lodi”’s reflective gaze and acoustic leanings.

-

CCR – “Wrote a Song for Everyone.” From the same Green River album, this is a slower, introspective cut that complements “Lodi”’s mood.

-

Gordon Lightfoot – “If You Could Read My Mind.” Less barroom, more parlor, but the interior weather feels related.

-

The Eagles – “Desperado.” A piano-led ballad about weariness and myth, perfect to follow Fogerty’s tale.

-

Townes Van Zandt – “Pancho and Lefty.” Storytelling with unhurried gravity; if you love narrative lyrics, you’ll hear kinship.

-

Waylon Jennings – “Dreaming My Dreams with You.” Country minimalism that prioritizes voice and lyric over adornment.

Each of these songs offers a different angle on the traveler’s lament—some more country, some more folk, some more rock—but all share the courage to be plain and the discipline to be concise.

The song’s quiet influence

It’s easy to measure influence by volume—by riffs copied or gear purchased—but “Lodi” exerts its pull in subtler ways. It’s been covered by artists across country and Americana for decades, often without drastic rearrangement. That’s telling: when a composition is this sturdy, performers change their own posture before they feel compelled to change the song. In teaching settings, it’s a gateway to arranging: students learn how to leave space, how to annotate a lead vocal with fills, and how to keep a groove alive at medium tempo. For writers, it’s a primer on scene building. You can sketch a town with one or two proper nouns; you can sketch a life with the right chorus.

Final reflections: the art of saying just enough

“Lodi” is persuasive because it practices humility. The band doesn’t grandstand; the lyric doesn’t over-argue; the production refuses to make a simple story “bigger” than it is. The result is a song that has aged as well as anything on Green River, and arguably better than many larger-than-life anthems from the same year. It’s music that breathes with you, that understands disappointment without trivializing it, and that finds melody in the pauses between plans. In an era fascinated with maximal options, “Lodi” offers a counter-lesson: choose carefully, play honestly, and trust the listener.

As you revisit CCR’s catalogue—or discover it for the first time—consider how “Lodi” refines the band’s strengths into a miniature. It’s not a spectacle; it’s a confidant. And like a good confidant, it tells the truth kindly. For anyone cataloging their favorite roots ballads, it’s an essential piece of music, album, guitar, piano conversation starter. Put it next to your own travel stories, the ones with long sunsets and longer goodbyes, and notice how it keeps finding new meanings at every age. That’s the quiet miracle of a classic: it grows without changing.