The year is 1969. The airwaves in Britain and America are thick with the dense, swirling psychedelia of the Summer of Love’s fallout, the thunder of hard rock, and the emerging earnestness of folk-rock. Then, the radio dial lands on something utterly singular: a rhythm that leans back when everything else is pushing forward, a guitar strumming with an unnerving, perfect syncopation, and a voice that soars in a beautiful, aching falsetto, singing words that few outside a tight Jamaican community could fully parse.

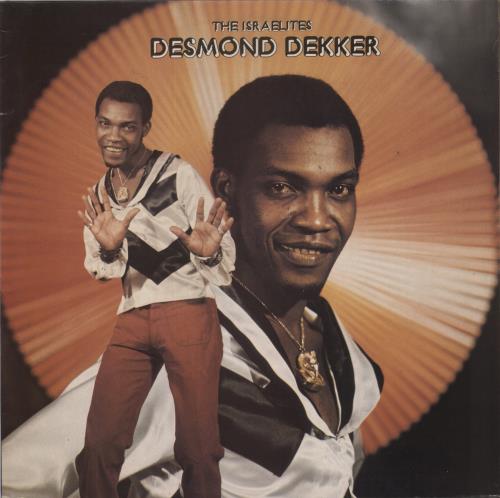

This was the cultural moment of Desmond Dekker & The Aces’ “Israelites,” a seismic single that didn’t just climb the charts; it cracked them open. Released internationally in 1969 (having first appeared in Jamaica in late 1968), it became the first Jamaican-produced song to hit number one in the UK and crash the US Top Ten, peaking at number nine. It was a victory for Jamaican music, for producer Leslie Kong, and for the man whose soulful, urgent plea introduced millions to the vibrant complexity of reggae.

I remember hearing it echo out of a small transistor radio on a beach vacation decades ago, the sound oddly perfect against the relentless crash of the waves. The beat, that famous ‘one-drop’ rhythm, seemed to move with a liquid, impossible grace, effortlessly cooler than the rock music I was obsessing over. That first exposure was a lesson: sometimes, the most revolutionary sound is simply the one that hasn’t been heard before.

The Sound of Struggle, The Sound of Joy

The success of “Israelites” can be traced directly to Desmond Dekker’s unique position in the evolving Jamaican music landscape. He had already established himself as a “rude boy” icon with 1967’s hit, “007 (Shanty Town),” a song steeped in the rebellious energy of the Kingston street youth. “Israelites,” originally titled “Poor Me Israelites,” shifts the focus from defiance to desperation, painting a vivid picture of a man struggling to survive, his wife and children leaving due to poverty.

“Get up in the morning, slaving for bread, sir, so that every mouth can be fed.” The opening lines are a blues cry dressed in the bright colours of rocksteady, the slower, more melodic genre that bridged ska and the emergent reggae. This piece of music is fundamentally about the daily grind, the economic anxieties that resonate whether you’re in Kingston, London, or Los Angeles.

The lyrics, delivered in a rich Jamaican Patois, were often misheard or misunderstood by international audiences, adding a layer of exotic mystery. Yet, the emotional core was undeniable. Dekker’s vocal performance is a masterclass in controlled agony, alternating between that trademark high tenor and a lower, more spoken-word delivery that lends the narrative absolute sincerity.

The Leslie Kong Touch: Arrangement and Rhythm Section

Credit must be given to producer Leslie Kong (who shares a writing credit), working out of his Beverley’s studio. Kong was one of the island’s most important figures, and his production on this single is crisp, tight, and foundational. He helped define the early reggae sound—a sound which emphasized the bass and drums, creating a mesmerizing dance between simplicity and syncopation.

The famous rhythm section provides the core texture. The bassline, far warmer and rounder than the average rock guitar bass, is pushed high in the mix, giving the track its characteristic forward propulsion, a low-end urgency that makes it impossible to sit still. The drums, often hit on the third beat, establish the quintessential ‘one-drop’ pattern, a hypnotic and revolutionary rhythmic device that feels sparse yet deeply funky.

The rhythmic guitar chop, the skank, is sharp and bright, playing on the upbeats. This is the guitar’s primary role here: not melody or riffing, but pure rhythm, an electric punctuation mark that keeps the entire track buoyant. This attention to the rhythm section made the record a phenomenon in dancehalls and clubs. I believe the best way to appreciate the rhythmic interplay is to listen with studio headphones, as they allow you to separate the bass, drums, and guitar skank in a way speakers often flatten.

The inclusion of the Aces’ backing harmonies—Winston Samuels and Easton Barrington Howard—is another crucial element. Their swooping, layered vocals provide an almost gospel-like response to Dekker’s lead, adding a depth of spiritual yearning that perfectly matches the ‘Israelites’ reference to Rastafari and the plight of the diaspora.

“‘Israelites’ isn’t just a song; it’s a perfectly distilled dose of rhythmic courage, delivering struggle with undeniable joy.”

The Legacy of the Single

“Israelites” was a non-album single, a promotional firework that launched the concept of Jamaican music as a global commercial force. An album titled The Israelites was released later in 1969 on the Pyramid label (a Doctor Bird subsidiary) to capitalize on the success, but the single itself was the trailblazer. It was a pivot point in Dekker’s career, consolidating his reputation from Jamaican star to international pioneer, paving the way for the later worldwide success of Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff, and the entire Trojan Records catalogue.

The song’s influence echoes through every subsequent wave of ska and reggae revival. It’s a reminder that global music exchange is not always a slow, gradual process; sometimes, a single, perfectly timed record can shift the entire cultural topography. A young punk fan, decades later, seeking to understand the origins of the Two Tone movement might be pointed toward this track for guitar lessons on rhythm technique. They would learn a lot more about musical structure than just a simple strumming pattern.

The enduring resonance of this 1969 masterpiece lies in its contrast: a lament of poverty set to a rhythm of pure, irrepressible joy. It is the sound of enduring hardship with dignity, a truly powerful statement delivered in less than three minutes, making it one of the most significant three-minute pop songs of its era. There is no piano solo or sweeping string section to distract; it’s just the raw, sophisticated interplay of human voice and rhythm. This enduring honesty is why “Israelites” remains an essential listen, a vibrant piece of musical history that still moves the feet and stirs the soul.

Listening Recommendations: Songs of Rhythmic Urgency and Pioneers

- Toots and the Maytals – “Pressure Drop” (1969): Shares the same raw, foundational early reggae beat and an urgent, soulful vocal performance.

- The Pioneers – “Long Shot Kick De Bucket” (1969): A contemporary single showcasing the rocksteady-to-reggae transition and rich backing vocals.

- The Melodians – “Sweet Sensation” (1969): Another Leslie Kong production that highlights the melodic sophistication and vocal harmony of the era.

- Jimmy Cliff – “Wonderful World, Beautiful People” (1969): Reflects the emerging international focus of Jamaican artists in the same year, with a message of social unity.

- Dandy Livingstone – “Suzanne Beware of the Devil” (1972): A later, similar UK reggae hit that captures the lyrical narrative and driving, light-footed rhythm.

- The Kinks – “Sunny Afternoon” (1966): Offers a non-Jamaican parallel in its use of irony and lyrical social commentary about the comfortable elite.