Bread’s “Everything I Own” is one of those rare ballads whose gentleness disguises its craftsmanship. Written and produced by David Gates and released in 1972, it became an emblem of early-’70s soft rock: unhurried, tuneful, sincere, and immaculately arranged. To many listeners it scans as a romantic confession, but Gates famously wrote it in tribute to his father—an insight that adds emotional weight to every line. What follows is a close listen to the record itself, with particular attention to the album context it came from, and the instruments and production choices that give the song its enduring warmth.

The album backdrop: Bread’s soft-rock summit

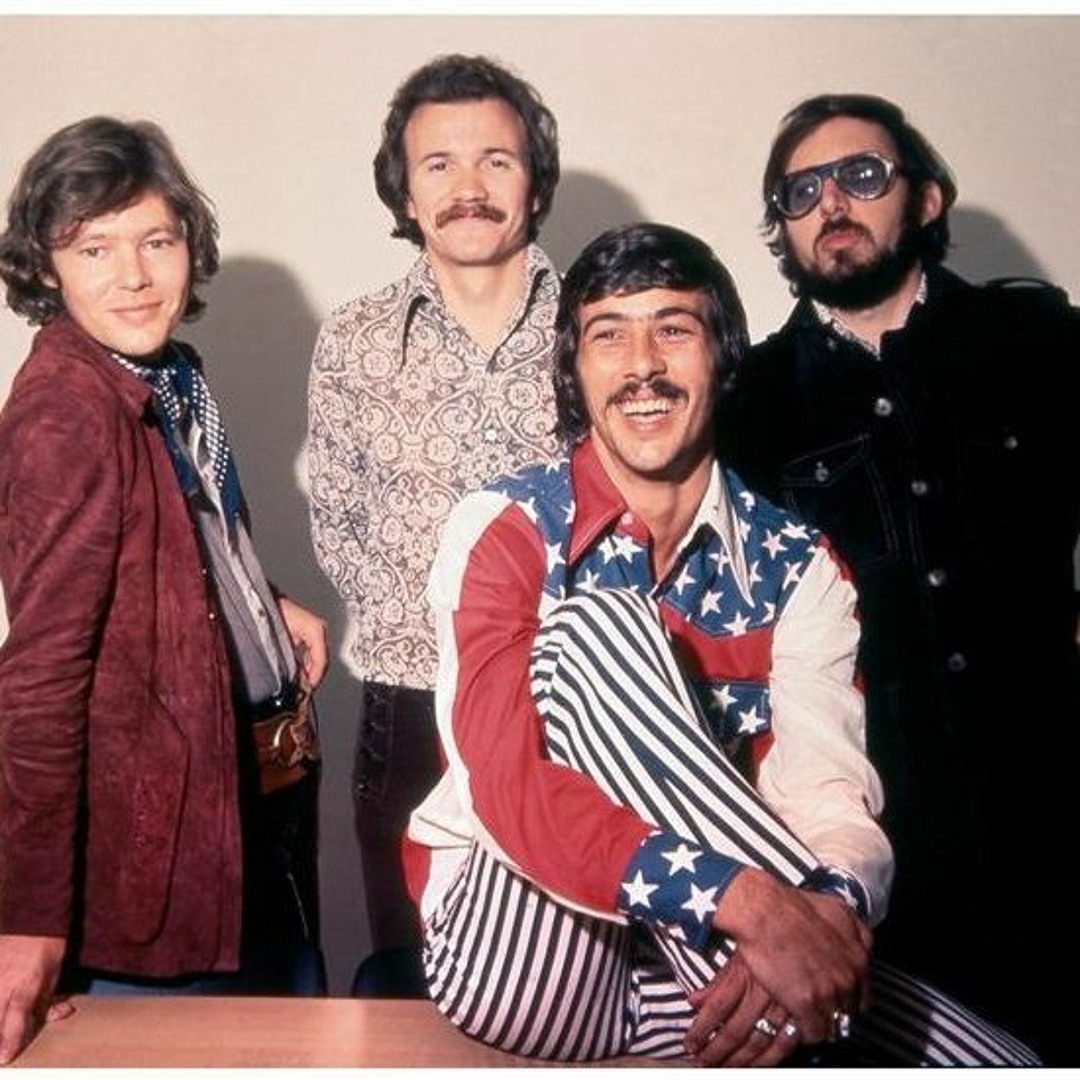

“Everything I Own” appears on Bread’s Elektra release Baby I’m-a Want You (1972), a pivotal album in the band’s arc. The record arrived as soft rock was crystallizing into a radio-defining sound, and Bread—by then the premier studio-savvy outfit of the form—leaned into clarity, melody, and restraint over spectacle. Baby I’m-a Want You threads together velvet-lined ballads and mid-tempo tunes with an almost chamber-pop polish, a sensibility fortified by the arrival of multi-instrumentalist Larry Knechtel alongside David Gates, James Griffin, and drummer Mike Botts. In this setting, “Everything I Own” functions as the album’s emotional centerpiece: a song that distills Bread’s core strengths—elegant songwriting, spotless ensemble playing, and tasteful studio decisions—into three and a half minutes of unaffected grace.

Although the album offers several highlights—“Diary” and the title track among them—“Everything I Own” is the cut where the band’s lyrical tenderness and sonic minimalism align most completely. In an era when progressive rock embraced grandiosity and country rock courted twang, Bread carved out a quieter lane: intimate, carefully layered, and welcoming to mainstream ears without ever feeling pandering. The record’s sequencing also flatters the song, handing it a corridor of space so its modest gestures feel larger than life.

Instruments and sound: the architecture of intimacy

At first blush the recording seems spare, but its minimalism is achieved by precise choices rather than simple subtraction. The principal instruments are:

-

Acoustic guitars: The bedrock of the track. You can hear finely picked arpeggios interlocking with gently strummed chords. The acoustic tone is round and close-mic’d, with the kind of soft top-end shimmer associated with high-quality steel-string instruments. The double-tracking is subtle; a listener might only register the sense of width and steadiness the way one notices a well-framed photograph rather than the frame itself.

-

Piano and electric keys: A restrained piano (often voiced in the middle register) places soft chords and connective tones between the guitars. There are hints of electric keyboard—likely an understated electric piano—to add pearly sustain without intruding on the vocal midrange. These keys are mixed like supportive furniture: you’d notice if they were gone, but they never call attention to themselves.

-

Bass guitar: The bass is round and supportive, sitting low but articulate. It tends toward stepwise motion and outline tones that emphasize the changes without a lot of ornament. Compression is tight enough to hold the notes in place, giving the bottom end a pillowy cushion rather than a thump.

-

Drum kit and light percussion: The drums are played with a velvet touch—close hats, brushed or lightly struck snare, and a kick that’s felt more than heard. The part avoids fills that would break the spell; instead it breathes with the vocal phrasing. A tambourine or shaker appears sparingly in the final choruses, adding a halo of motion.

-

Strings (or string-like textures): You’ll hear a small, lush string sheen that swells under key phrases and resolves with the harmony—arranged to color emotion, not dictate it. Whether tracked as a small ensemble or overdubbed section, the strings lift the chorus without thickening the mix unduly.

-

Vocals and harmonies: Gates’ vocal is the center of gravity: breath-supported and clear, with barely any grit. The harmonies, likely layered by the band, enter like a soft tide during the chorus. Slight double-tracking on the lead gives the voice a dimensional glow without losing intimacy.

On the production side, the palette is a hallmark of L.A. studio craft of the era. EQ carves a pocket for the voice; gentle compression keeps the dynamic range smooth; and plate reverb (think classic studio plates) is dialed in short enough to suggest a room rather than a cathedral. Panning is classic: acoustic guitars providing stereo breadth, bass and kick locked to center, piano slightly off-center, strings painting the periphery when they arrive. Nothing is loud for its own sake. The cumulative effect is a living room performance captured with surgical finesse.

Song design: a lesson in emotional economy

“Everything I Own” demonstrates how a song can be harmonically straightforward and yet emotionally sophisticated. Verses open like a conversation, with uncomplicated diatonic movement that keeps the listener oriented. The chorus steps up modestly in register and density—never with brute force, but with an elegant increase in harmonic support and vocal layering. The melodic line conveys a private admission: it rises where the lyric confesses and resolves where the lyric consoles. If you map the melody’s contour, you’ll notice it favors stepwise motion with occasional yearning leaps—intervals that feel like reaching for, and then returning to, home.

Rhythmically, the groove is a soft rock heartbeat; nothing gallops or drags. The drums lay down a pocket that is simultaneously steady and unassuming. The bass complements this by playing legato lines that “breathe” with the vocal rests. Because the arrangement refuses to overplay, micro-details become dramatic: a held syllable, a bass pickup note, a passing chord clustered on piano that briefly shades the harmony before clearing to the acoustic guitar bed.

Country tenderness, classical poise

What makes the record so appealing across styles—including to fans of country and classical music—is its discipline. Country songwriting values plainspoken emotion; classical traditions value proportion and balance. “Everything I Own” sits at their intersection. The lyric says a profound thing in direct language, while the arrangement applies classical restraint—sparing string lines, voice-leading that coils and releases without showing the wire. The result is dignified rather than dramatic, more like a cherished letter set to music than a confession shouted from a rooftop.

This dual affinity also makes the song a remarkable study in piece of music, album, guitar, piano aesthetics: how a tender text, sung without affectation, rests on a small ensemble that plays like a chamber group. You could strip the song down to voice and one instrument and it would still work; add the ensemble and it becomes three-dimensional.

Performance notes: singing and playing the song

For singers, the challenge is breath control and sincerity. Gates places phrases so each one feels conversational, avoiding the temptation to oversing. For guitarists, the right hand must balance arpeggios and light strums without crowding the vocal. Pianists should think in terms of supportive voicings—close-position triads with tasteful extensions—played like velvet cushions under the singer. Drummers and bassists should aim for an unbroken, cradle-like pocket: think of the groove as the song’s pulse rather than its engine.

If you’re learning the tune, it’s also a rewarding vehicle for arranging skills. Try beginning with solo voice and guitar, then gradually add piano, bass, and finally a small string pad in the final chorus. This orchestrated bloom mirrors the record’s emotional arc. Listeners who audition equipment with this track will appreciate how much information is tucked into small gestures; it’s a lovely test piece for the best headphones not because it’s flashy, but because clarity, decay, and stereo spread are so carefully rendered.

Lyrical reading: gratitude widened to universality

Knowing that Gates wrote the song for his father reframes the lyric without closing off other meanings. Lines that initially read as romantic suddenly carry the humility of filial gratitude. That’s why the song has functioned so well in settings as varied as memorials, anniversaries, and quiet evenings alone—it gives the listener room to map their own story onto it. The melody’s patient unfolding reinforces this intimacy; there’s always the sense that confession is being offered, not demanded.

Covers and cultural afterlife

A song built on clarity and feeling invites reinterpretation, and “Everything I Own” has flourished in new guises. Ken Boothe’s 1974 reggae version transformed the harmony’s soft sway into a rocksteady lilt and shot to No. 1 in the UK, a testament to how transportable Gates’ melody is across rhythmic languages. More than a decade later, Boy George’s 1987 cover likewise topped UK charts, his androgynous timbre opening the lyric to fresh ambiguities. Numerous other versions—country-flavored, orchestral, acoustic—confirm a core truth: when a melody is sturdy and a lyric honest, style becomes a set of clothes rather than a cage.

This broad afterlife has a useful side effect for musicians and listeners alike. For learners, exploring multiple arrangements is an education in adaptation—how to keep the song’s heart alive while changing tempo, groove, or harmonic color. For listeners, comparing the original with later versions sharpens one’s sense of why the Bread recording still feels definitive: it’s the equipoise of timbre, touch, and tempo that’s hard to better. If you’re pursuing online guitar lessons, the tune is approachable and a fine study in balance—never too many chords, never too few.

Why it endures

There is a deeper reason “Everything I Own” still lands. Many ballads of its era aim for catharsis; this one aims for candor. It’s musical empathy. The record refuses melodrama and finds a steadier, truer current—the musical equivalent of a hand on the shoulder. Technically, it is a masterclass in frequency-zone cooperation: the voice occupies the midrange; acoustic guitars provide rhythmic chime above and below; piano fills knit the fabric; bass and drums supply a pulse that says “trust me, we’re here” rather than “follow me, we’re going.” Artistically, it’s a portrait of gratitude given a tune so natural you feel you’ve always known it.

Listening recommendations: if you love this, try…

If “Everything I Own” speaks to you, there’s a family of songs that share its clarity, softness, and sincerity:

-

Bread — “Diary”: Another Gates gem from the same Baby I’m-a Want You album, intimate and diary-true, with the same silken production touch.

-

Bread — “Aubrey”: From the later Guitar Man album, a hushed, almost chamber-pop reverie with luminous string writing.

-

Bread — “Make It with You”: The band’s earlier breakout hit, meltingly melodic and a template for soft-rock tenderness.

-

James Taylor — “Fire and Rain”: Confessional folk-rock with pristine acoustic guitar work and a quietly indelible melody.

-

John Denver — “Annie’s Song”: A breath-like melodic arc that, like Gates’ writing, makes intimacy feel universal.

-

Randy VanWarmer — “Just When I Needed You Most”: Late-’70s soft-rock ache with acoustic guitar at the center, stylistically adjacent to Bread.

-

Don McLean — “Vincent”: A folk-tinged ballad whose gentle guitar and painterly lyricism complement Bread’s sensibility.

-

Bee Gees — “How Deep Is Your Love”: A later soft-soul classic; note the way the vocal harmonies and gentle rhythmic bed mirror Bread’s emphasis on restraint.

Each of these recordings shares some DNA with “Everything I Own”—delicacy of arrangement, melodic directness, and that elusive feeling of a song speaking at room volume yet carrying across a lifetime.

Final thoughts

More than a nostalgic relic, “Everything I Own” remains a living example of how understatement can magnify feeling. Set within the sympathetic frame of Baby I’m-a Want You, it shows Bread at their most distilled: melody first, arrangement in quiet service, performance without flourish. The instrumental choices—acoustic guitars laid like silk, a considerate piano, supportive bass, heartbeat drums, and strings that sigh rather than soar—build the sonic architecture of trust. Listeners new to the band will find here an ideal starting point; those who grew up with it will likely hear anew the meticulous decisions that make it glow.

In an age that often mistakes volume for intensity, Bread’s ballad whispers and is heard. It’s the kind of song that turns a room inward, that prompts gratitude rather than grandstanding. And it is a reminder that when a melody is honest, a lyric is plainspoken, and the arrangement respects silence, the music does what it was meant to do: it moves us—quietly, lastingly, and without end.