If you could bottle joy, it might sound a lot like Three Dog Night’s “Shambala.” Released in 1973 and folded into the band’s tenth studio LP, Cyan, the track became one of the defining radio anthems of early-’70s pop-rock: concise, buoyant, and spiritually tinged without ever losing its sing-along core. It climbed to No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 and also topped the Cash Box chart, a testament to how completely it captured that summer’s appetite for hopeful, harmony-rich choruses and a backbeat you could steer a convertible by.

The album context: Cyan as a turning point

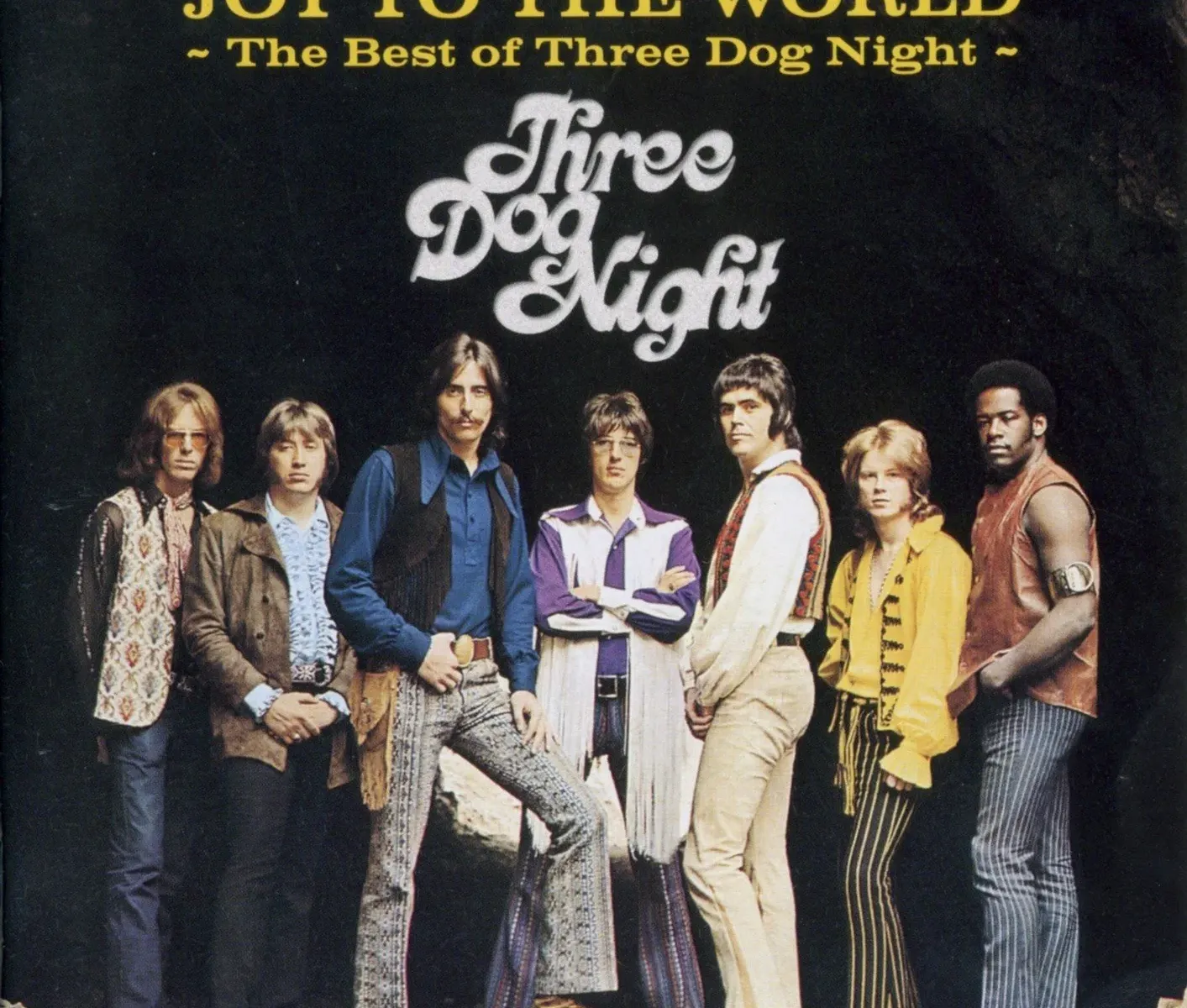

Although “Shambala” first arrived as a single in May 1973, it soon anchored Cyan, released on October 9, 1973, by Dunhill Records. Produced by Richard Podolor and recorded at American Recording Co. in Studio City, California, the album sits at an interesting midpoint in Three Dog Night’s run of hits—after the one-two-three of “Black & White,” “Pieces of April,” and “Joy to the World,” but before 1974’s Hard Labor. Cyan reached No. 26 on the U.S. Top 200 and cracked the Canadian Top 10, with “Shambala” and “Let Me Serenade You” serving as its twin radio engines. These facts matter for understanding the song’s place: it wasn’t just another standalone smash, but the star around which an entire LP cohered.

The Cyan track list also highlights the band’s eclectic curation—originals from guitarist Mike Allsup, a John Finley tune (“Let Me Serenade You”), a Seals composition (“Ridin’ Thumb”), and the Daniel Moore-penned “Shambala.” That mix of outside writers and in-house ideas was a Three Dog Night signature, and Podolor’s steady hand ensured the LP sounded like a single statement rather than a compilation of unrelated singles. The album credits (Podolor producing, Bill Cooper engineering; arrangements credited to Podolor and the band) show a mature studio machine capable of framing each song as a concise radio vignette while keeping the LP’s color palette—those deep blues of organ and the sunlit cream of vocal stacks—consistent across the sides.

Voices up front, band in lockstep

Three Dog Night’s great trick was making three lead singers feel like one extroverted, many-headed storyteller. On “Shambala,” Cory Wells takes the lead—his timbre warm yet edged with grit—while Danny Hutton and Chuck Negron interlace jubilant harmonies around him. That assignment matters: Wells had a soulful directness that could sell both the groove and the song’s quasi-mystical imagery without tipping into parody. Meanwhile, the band’s classic lineup locks in behind him: Michael Allsup’s strummed acoustic/electric blend, Jack Ryland’s rounded bass, Floyd Sneed’s springy drums, and Jimmy Greenspoon’s piano/organ foundations. The personnel and vocal crediting for the album confirm this balance of roles, and it’s a model of how arrangement choices amplify a lyric’s meaning.

Instrumentally, “Shambala” radiates upward. The beat is straight and buoyant—kick and snare planted like fence posts—yet the percussion feels splashy and communal, with tambourine accents that lift each chorus. The guitars are mostly rhythmic—open-chord strums that churn like a jubilee—while a bright piano locks hands with organ swells, creating a simple but generous harmonic frame. Rather than busy riffs, Allsup offers connective tissue; rather than florid solos, Greenspoon’s keys color the edges and urge the singing forward. It’s a study in restraint serving euphoria: every player focuses on uplift, leaving just enough sonic air for the three voices to bloom.

For audio craft nerds, notice how the mixes tend to keep the bass and kick plush rather than thumpy; Sneed’s snare is crisp but not brittle; and the backing vocals are stacked to feel like a congregation surrounding the lead, not an overdub pasted on top. That aesthetic flows from Podolor and Cooper’s American Recording Co. playbook—clarity first, then warmth—one reason these records have aged so well on modern systems.

Lyric path: from Tibet to Top 40

Daniel Moore’s lyric draws on the myth of Shambhala—spelled “Shambala” here—a legendary kingdom in Tibetan Buddhist tradition sometimes used in Western pop culture as a metaphor for an enlightened community. Moore flips the idea into a road song: the promise isn’t just a destination but the act of traveling there, a journey where kindness accumulates, fear rinses away, and burdens are traded for fellowship. That’s a clever transposition for pop: it keeps the imagery open-ended and inclusive while letting the chorus function as a portable mantra. In typical Three Dog Night fashion, the band doesn’t sermonize; they celebrate. Wells’s lead calls out the vision, and the harmony section answers like a crowd that already believes.

Groove anatomy: how “Shambala” works on the body

The record’s euphoria begins in the drum pocket. Sneed drives an even, medium-fast tempo that invites clapping on two and four. Against that, Ryland’s bass avoids acrobatics; instead, it pulses with short, rounded notes that make the pattern feel like a wheel rolling forward. The guitars—mainly open chords—provide percussive chatter in the midrange, while piano and organ supply both harmonic pad and punctuating fills between phrases. It’s all about forward motion, the musical equivalent of a caravan cresting a sunlit ridge.

Then there’s the band’s peerless vocal arranging. Three Dog Night were masters of “call-and-response” built for AM radio: a declarative lead line followed by stacked harmonies that answer in agreement. On “Shambala,” that technique translates the lyric’s communal ideal into sound. You hear a single voice reach toward a better world; you hear many voices say, “We’re coming with you.” It’s that emotional architecture, more than any one riff, that makes the record feel like shared catharsis. (For collectors and arrangers who care about search terms like piece of music, album, guitar, piano, this is a near-textbook example of balancing rhythmic strum, keyboard pad, and vocal massing.)

Production values and sonic character

Podolor’s production aesthetic prizes transparency: every element has a clear seat in the stereo field, and nothing overstays its welcome. Listen to how the intro springs open with instantly intelligible layers; how the choruses add width via backing stacks and hand percussion rather than radically changing the core instrumentation; how the break never drifts into indulgent soloing but keeps the attention on the collective voice. Bill Cooper’s engineering keeps transients lively without harshness—one reason the record holds up beautifully on modern playback chains. Cue it on a good system and you can practically count the layers of harmony in the choruses and the piano’s percussive strikes riding just above the rhythm guitar bed.

Chart story and cultural footprint

Part of “Shambala”’s enduring appeal is that it brought spiritual vocabulary into mainstream pop without the heaviness that sometimes dogged early-’70s “message music.” Listeners voted with their ears: the single shot to No. 3 on Billboard’s Hot 100 (and the U.S. Adult Contemporary chart) and hit No. 1 in Cash Box, while Cyan itself earned a gold certification and a respectable Top-30 album berth. The band’s ability to translate outside songwriters’ ideas into their own three-singer language helped them stack an astonishing 21 U.S. Top 40 hits between 1969 and 1975—“Shambala” among the brightest of that run.

It’s also worth noting that Moore’s tune had a near-simultaneous competing version by B.W. Stevenson in 1973, a reminder of how quickly good material could spread in that era. Three Dog Night’s reading won the airwaves decisively, not because it was louder or flashier, but because the arrangement made the communal promise feel contagious.

Country and classical lenses: why it connects across genres

Coming from a background steeped in country and classical music, I hear “Shambala” as a canny fusion of gospel call-and-response with pop-rock craft. The chord language is simple and diatonic—closer to a hymn or a country camp-meeting chorus than to bluesy R&B changes—while the vocal phrasing leans on unison openings that flare into triads and sixths, a move you might recognize from church choirs or the finales of classical oratorios. The acoustic strum has a whiff of country campfire; the piano-organ blend nods to both Southern gospel and symphonic pad thinking (sustained tones filling the spectrum). That cross-pollination helps explain the song’s cross-demographic success: it feels familiar to roots listeners without alienating pop audiences.

Even the narrative stance—the promise that burdens will be washed away “on the road” rather than at the journey’s end—echoes the traveler’s metaphors that thread through American folk and country music. If you love the structural clarity of classical forms and the heart-on-sleeve storytelling of country, “Shambala” hits a sweet spot: clean design, big feeling.

How to listen today

In 2025, the track remains a model of radio-ready euphoria. On contemporary music streaming services, you’ll find remasters that preserve the snap of Sneed’s snare and the shimmer of Greenspoon’s piano. This is also a terrific track to test the imaging of your setup—those backing vocals should arc across the speakers like a half-smile. If you’re spinning vinyl, a good copy of Cyan delivers satisfying warmth; if you’re on the go, even a decent pair of the best wireless headphones will reveal the interplay between organ swells and acoustic guitar strums. (Bonus: it’s a perfect car-window-down song—moderate tempo, endless chorus.)

Instruments and sounds: the palette in focus

-

Lead vocal: Cory Wells. His approach is declarative but smiling; he pushes the melody forward and trusts the choir behind him to widen the emotional frame.

-

Harmony vocals: Danny Hutton and Chuck Negron. Their blend is the band’s not-so-secret weapon, delivering a gospel glow that never turns preachy.

-

Guitars (Michael Allsup): Primarily rhythmic strums with occasional electric glints; the role is less “soloist” and more “engine,” an endlessly churning propeller.

-

Keyboards (Jimmy Greenspoon): Piano provides attack; organ paints sustain. The combination keeps the mix bright without sacrificing body.

-

Bass (Jack Ryland) and drums (Floyd Sneed): A cushion rather than a spotlight—round notes, tasteful fills, pocket first.

-

Percussion: Tambourine/handclaps amplify the communal feel; you can practically hear the room smiling.

Notice how none of these parts fight for dominance; they’re designed to interlock. The production declines the temptation of flashy overdubs in favor of a lived-in groove where the chorus can bloom every time. In a classroom setting, it’s a superb case study in arranging for three lead voices while retaining radio concision—something bands as far afield as country-rock ensembles and modern worship collectives still chase.

Recommended listening pairings

If “Shambala” lights you up, try these tracks next for a coherent mini-playlist that leans into jubilation, spiritual motifs, and robust harmony work:

-

B.W. Stevenson – “Shambala.” The parallel 1973 cut is earthier and a touch looser; hearing it back-to-back with Three Dog Night’s version shows how arrangement can shift the center of gravity.

-

Three Dog Night – “Let Me Serenade You.” From Cyan, with another roof-raising chorus and vivid organ colors; it reached the U.S. Top 20 later that year.

-

Norman Greenbaum – “Spirit in the Sky.” Gospel-rock at its most iconic; fuzz guitars in place of sunny piano, but the same communal uplift.

-

Dobie Gray – “Drift Away.” A masterclass in feel; less overtly spiritual, but the chorus embraces and reassures in a similar way.

-

Ocean – “Put Your Hand in the Hand.” Pop-gospel DNA that tilts a little more explicitly toward church, with piano leading the way.

-

Bellamy Brothers – “Let Your Love Flow.” Country-pop warmth and a rhythm guitar engine that scratches the same itch for open-road optimism.

Final thoughts

“Shambala” endures because it is both a great record and a great feeling. It’s a communal chorus captured in under three-and-a-half minutes, a vision of a kinder world that never scolds or lectures. Wells’s vocal centers the promise; Hutton and Negron enfold him in harmonies that feel like good company; Allsup, Greenspoon, Ryland, and Sneed keep the caravan moving with an unfussy, sunshine-toned groove. And Podolor and Cooper—quiet craftsmen—frame it all so cleanly that half a century later, you can still sit back and trace the outline of every instrument while getting swept up in the shout.

Heard within Cyan, the song is even more satisfying: the LP context gives it gravity, and the surrounding tracks show how adaptable the band’s three-singer architecture could be. Few singles better capture why Three Dog Night mattered in the first place: they were curators and translators who could take a songwriter’s metaphor—here, a mythic city of compassionate living—and make it feel like the chorus that breaks out when a carload of friends spots the ocean. It’s pop as fellowship. Spin it again, and you may find that, for three minutes and change, the road to a better place is as simple as clapping on two and four and adding your voice to the refrain.