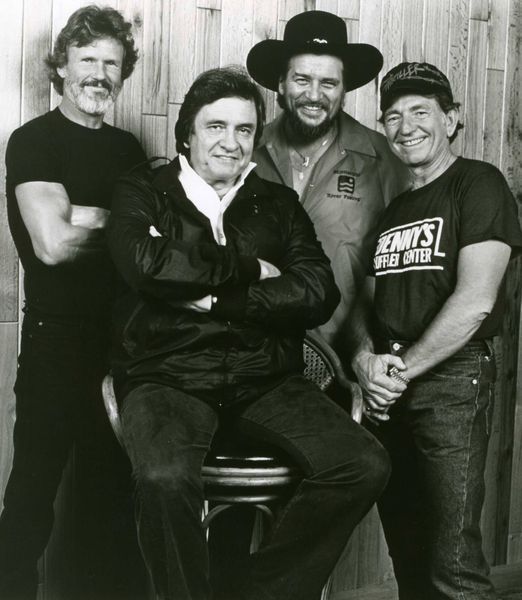

Four legends, one stage, and a story that rides across time—Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson didn’t just sing “Silver Stallion,” they embodied it. Watching them trade verses feels like witnessing a piece of history, a raw, unfiltered moment where the myth of the West meets the grit of four icons who lived it. It’s more than a song; it’s the kind of lightning in a bottle that captures the “thundering of his feet” and the soul of American music in one frame.

The first thing you hear is confidence. Not the swaggering kind, but the lived-in steadiness of four voices who’ve stared down crowds and bad weather and deadlines, then walked onstage anyway. “Silver Stallion” doesn’t explode; it arrives like a rider cresting a ridge, steady gait, dust kicking up behind. The Highwaymen—Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and Kris Kristofferson—treat Lee Clayton’s song like a shared vow, each verse an angle on the same horizon. As an opening track and lead single from Highwayman 2 (1990), it sets the terms for the record: minimal showboating, maximum presence.

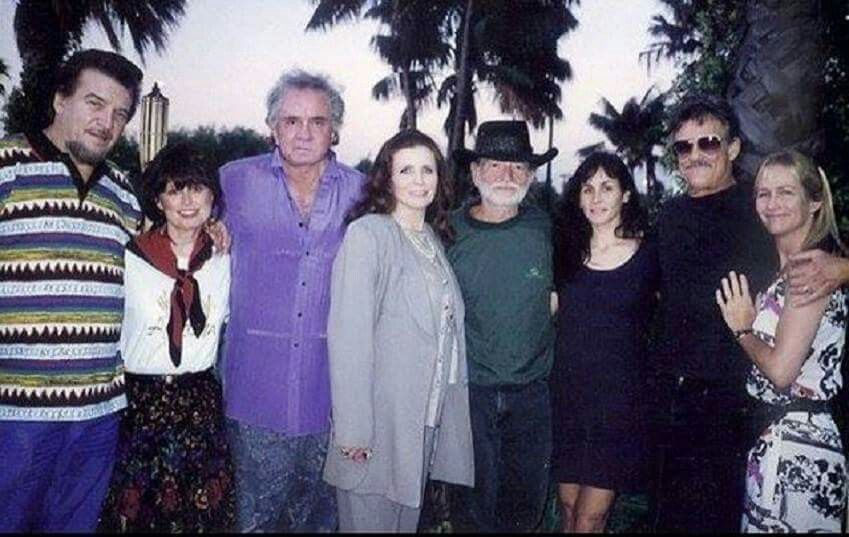

To place it properly, you have to remember where these men were in 1990. The first Highwaymen album had already proven the chemistry of this once-in-a-generation supergroup. Country radio, meanwhile, was shifting younger and glossier, but the quartet reconvened with producer Chips Moman, the architect behind their debut and a longtime collaborator to Nelson and Jennings. Highwayman 2 came out on Columbia Nashville—a “homecoming” for Cash, whose final Columbia work this would essentially be—recorded the previous year in Nashville, Memphis, and Spicewood, Texas. That lineage matters, because it explains the blend of polish and grit: Moman’s ear for contemporary sheen, anchored by veteran players and four voices that cut through any decade’s production tricks.

“Silver Stallion” itself began with Lee Clayton, who originally released it on his 1978 album Border Affair. The Highwaymen treated his outlaw dreamscape not as cosplay but as continuation, a reaffirmation that freedom songs don’t expire with trends. Their version rode the U.S. country charts into the Top 30—peaking at No. 25—and came with a music video that made its myth plain: four men, four legacies, one road.

The arrangement is spare but not skeletal. Listen to how the rhythm section plants its heels—Gene Chrisman’s drums landing with purposeful weight, Mike Leech’s bass outlining the trail with a low, unhurried walk. Over that, guitars come in like weather fronts: Reggie Young with his unerring taste, Johnny Christopher with unfussy comping, and the spectral cry of Robbie Turner’s steel tracing the skyline. Bobby Emmons and Bobby Wood add discreet keyboard color, never jostling vocals but lending a faint, wind-as-organ backdrop. It’s the kind of band Moman loved to assemble, the kind that knows restraint isn’t the absence of feeling but its containment.

What makes the performance work is how the four leads split the song without fracturing it. Cash takes a line and immediately stakes the moral terrain—authority without force. Jennings arrives with that cool, slightly nasal glide, hand on the wheel of the verse like a driver who’s already learned every curve of this road. Nelson threads his phrases conversationally, slipping just behind the beat in the way only he can, a reminder that time is elastic when the singer owns it. Kristofferson leans into the weather of his tone, the cracked-leather texture that makes every image feel hard-won rather than borrowed. The chorus doesn’t belt; it binds, the quartet moving as a single unit, like riders who’ve learned to keep formation without talking about it.

Moman’s production has been called “of its moment,” but that’s part of the song’s charm. There’s a quiet gloss to the mix—the drums slightly forward, the guitars layered in a gentle halo—that speaks to late-’80s/early-’90s studios. Yet the bones are classic. A single mic won’t catch four decades of road dust, but the vocal blend suggests a shared room: air moving around these timbres, breath and consonants folding into one another. Some contemporary listeners might wish for rawer edges, yet the record proves you can streamline without sanding away soul.

If you isolate the details, the track’s architecture reveals itself. The “attack” on the acoustic strum is soft, almost brushed, creating a bed that lets the electric figures peep through at the phrase ends. Steel guitar isn’t smeared across everything; it’s placed with almost cinematographic intent, slipping you from medium shot to wide shot, horizon opening in the reverb tail. The drums avoid big fills, preferring the stoic backbeat that implies distance traveled rather than drama manufactured. When the harmony stack enters, the blend is more oath than choir—no ornamental vibrato, just four signatures aligning on a dotted line.

“Silver Stallion” works as myth, but it also works as craft. Clayton’s writing balances emblem and motion—“stallion” reads as symbol, “ride” reads as verb. The Highwaymen honor both. When they sing together about riding, they don’t posture as eternal youth; they sound like men who know exactly what it costs to keep moving. That’s the paradox of the cut: a promise of flight delivered by voices that have already paid the toll.

As an opener, it frames Highwayman 2 as a conversation with time. Moman surrounds the group with measured layers—electric guitars like sun flares, keyboards like heat haze—and the sequencing places “Silver Stallion” as the invitation to the journey. A different band might have turned it into a chest-beating anthem. Here, it’s closer to a benediction for the road ahead, a handshake to the listener. The record went on to reach No. 4 on the country album chart and snag a Grammy nomination for Best Country Vocal Collaboration, but you don’t need plaques to hear why this track sits at the front. It tells you what kind of company you’re keeping.

I like to imagine a late drive with this song because it invites you to make a small film of your own. The lines aren’t dense, and the tempo doesn’t push, so your mind has room to cut. Mile markers tick by; the road noise becomes percussion; the center-line dashes blur and reappear. Everything about the track is cleanly voiced—the kind of “piece of music” you can lean into without having to brace for impact.

One micro-story: a commuter heading out of town after a long week, windows cracked to the evening, finding in that unison chorus a little fellowship in forward motion. No one announces courage there; it’s simply practiced mile by mile.

Another: a parent teaching a teenager to drive on a county road, radio low, the song’s calm steadiness modeling how to hold a lane through small uncertainties. The lyric’s imagery feels cinematic to the kid; to the grown-up, the voices register as living history sitting quietly on the dash.

A third: someone at a crossroads—job, relationship, home—packing boxes at midnight. The song comes on a playlist and doesn’t hand out advice. It just lays down that pulse, a reminder that moving on needn’t be a sprint. Sometimes you just ride.

Quote me on this:

“Four voices, one horizon—‘Silver Stallion’ doesn’t gallop so much as it keeps faith with the road.”

Listen closer to the interplay. There’s a point where a tremolo-kissed electric flickers under the vocal—barely there, like heat lightning—then recedes into the texture. That’s Reggie Young’s kind of touch, a masterclass in saying more by saying less. A harmonica ghost from Mickey Raphael threads a fleeting line, the sort of cameo you notice only on headphones, but once you hear it, you anticipate it every time. A steel phrase lifts a cadence like a horizon line rising, then disappears before the ear can cling. This is arrangement as trust: no one elbowing for the frame, everyone confident that the song will carry them if they carry the song.

Vocally, you can map identity onto grain. Cash is the floorboard—oak-solid, resonant. Jennings is the wheel—easy, directional. Nelson is the suspension—subtle give that makes rough stretches feel navigable. Kristofferson is the odometer—evidence of distance, a reading you believe precisely because it shows the wear. When they merge on the chorus, it isn’t to flatten difference; it’s to let contrast become chord. That’s harder than trading verses. It requires listening equal to singing.

Because the production bears the era’s fingerprints, “Silver Stallion” often becomes a test of what you value in records. If you chase raw tape hiss and mistakes left in, you might initially hear this as too careful. Yet the care has a point. By 1990, these men had nothing to prove except that they still knew how to choose and deliver songs. Their restraint is a kind of pride. And in a catalog where blaze-ups and barnburners get the headlines, it’s good to have a track that looks you in the eye and says, “We’ll get there.” The fact that it charted, nudging its way up the Hot Country Songs tally, simply confirms that listeners recognized the promise when they heard it.

As part of the group’s career arc, “Silver Stallion” signaled durability. The Road Goes on Forever would come five years later with Don Was at the helm, but this was the last Columbia chapter for Cash and a fine send-off on that label. Highwayman 2 also broadened authorship within the group: Nelson and Kristofferson brought in material, Jennings co-wrote elsewhere on the record, and the repertoire felt less like a victory lap and more like a second wind. You can hear that in the first 30 seconds of the opener.

For sound-focused listeners, this cut rewards playback care. The vocal blend in the chorus, the steel’s decay, the way the kick and bass find each other—all sit in a frequency pocket that opens up on decent speakers. If you’ve invested in thoughtful home audio, the mix assumes an almost three-dimensional snap: the guitars stage left and right in light counterpoint, the lead vocal centered but not glued to the cone. On good studio headphones, the room bloom around the stacked parts reveals itself—subtle but satisfying.

Instrumentally, it’s instructive to notice how little “soloing” happens. The guitar work behaves like a companion rider, keeping pace, occasionally pointing to a landmark, never dragging your gaze away from the path. Keyboard figures hover toward the edges, more road shimmer than billboards. If you strain to identify pure “piano,” you may realize that on this cut the keyboard timbres skew toward organ and electric textures rather than hammered acoustic strings—another way the track keeps its austerity clean. But the ghost of a piano’s percussive logic is there, guiding chord changes with a light hand.

There’s also cultural patience in the song. By 1990, country had already thrown multiple cycles of fashion at its artists. The Highwaymen didn’t chase any of them here. They chose a lyric that could hold four distinct American mythologies and an arrangement humble enough to let each man’s story breathe. That’s why the performance has aged better than some of its surface choices might suggest. You can remix a snare; you cannot remaster conviction.

Crucially, “Silver Stallion” is not nostalgia pretending to be rebellion. It’s older men putting rebellion in context—less about breaking out, more about carrying on. When they sing together, you hear generations of rooms, cheap monitors, tour buses, small emergencies solved by good humor and stubbornness. That history turns the stallion from metaphor into memory, and the ride into a ritual.

If you’re approaching the track as a musician, pay attention to the pocket discipline. No one rushes the downbeat. No one flutters on the line-end holds. The tempo is mortal and trusting. That patience is a lesson—one that shows up in your own playing after approximate repetition, whether you learned via piano lessons or by banging through changes with friends in a garage. Songs like this teach you to leave space, then believe the space will hold.

The Highwaymen’s “Silver Stallion” is also a reminder that covers can be acts of stewardship. Clayton’s original remains a weathered beauty—longer, more solitary, with a slightly different atmosphere. The 1990 rendition doesn’t erase that; it builds a communal porch onto it. Cat Power would later reinterpret the tune on Jukebox (2008), proof that the melody and myth travel well, but the Highwaymen version anchors the standard in four-person harmony, a reference point for any future rider who wants to take the journey in company.

In the end, the song’s power is practical. It invites you to go somewhere—across town for a talk you’ve been avoiding, or across years to a version of yourself that once believed roads were endless and open. The record guarantees nothing. It only accompanies. Which is, if you think about it, the thing we most need from music when the map blurs: a steady beat, a patient chord, a few voices that have seen some miles and still choose to sing.

And when the last chorus fades, what lingers isn’t the stallion’s shimmer but the riders’ companionship. Put it on again. The trail will look different the second time.