In the smoky glow of a small-town honky-tonk, a young Merle Haggard once sang with the raw honesty that would later define his career. “Falling for You” carries that same spirit — a tender confession wrapped in simple words, yet heavy with emotion. It’s the story of a man caught between toughness and vulnerability, where love disarms him more than life’s hardships ever could. Listening to the song feels like stepping into Merle’s heart, where every line lingers with both longing and surrender. His voice, rich and unpolished, draws you into the moment — a reminder that even the most hardened souls can be undone by love. “Falling for You” isn’t just a country song; it’s a timeless portrait of the fragile beauty that lives inside us all. When Merle sings, you don’t just hear the music — you feel his truth.

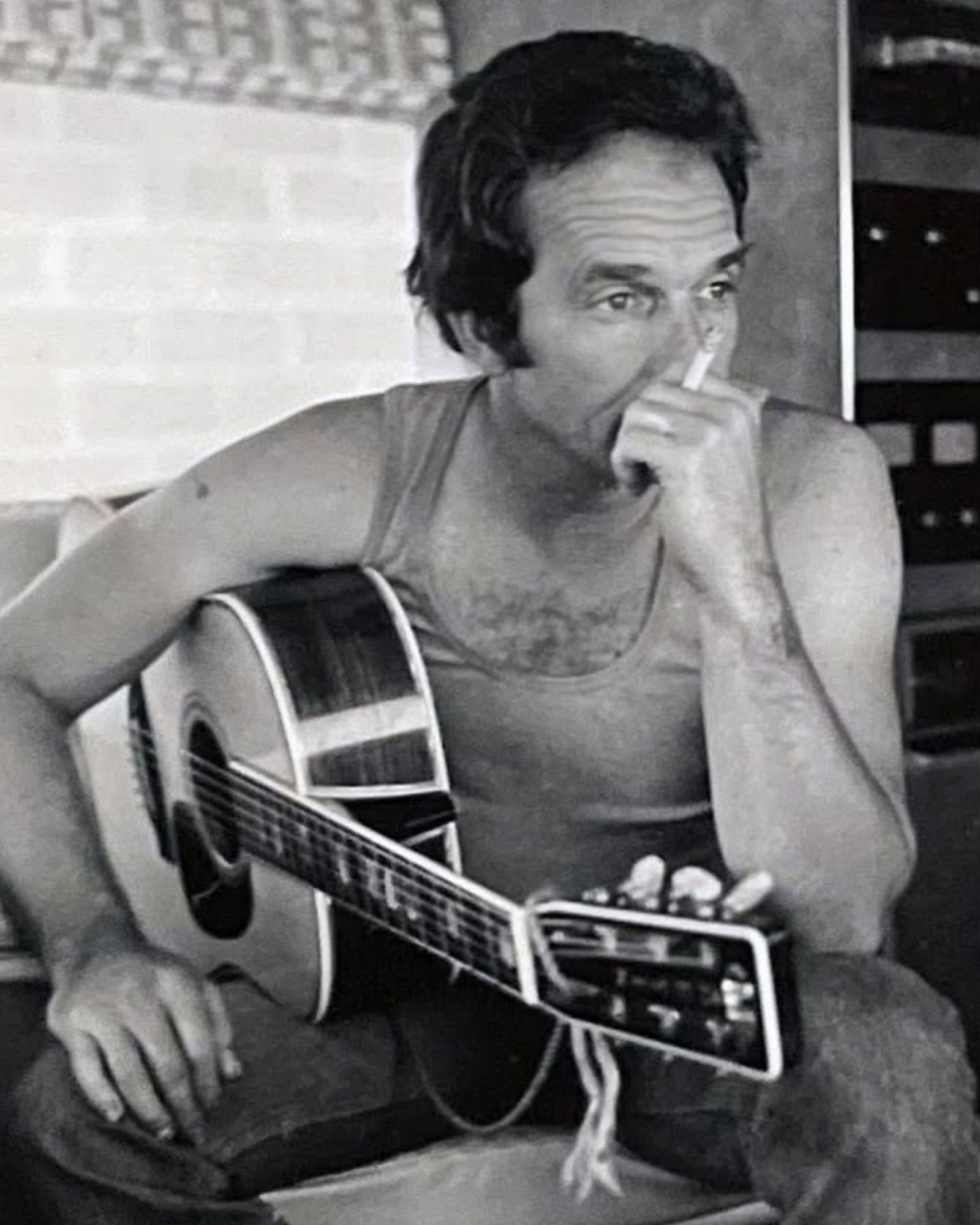

I first hear the shuffle, not the singer. A gentle tick of drums and the brush of cymbals draw a circle in the air, as if the band is sketching a room before anyone speaks in it. Then the steel sighs—one measured slide, just enough to place you at a neon-lit bar where two voices across the room might be about to change your night. On “Falling for You,” Merle Haggard doesn’t raise his voice. He doesn’t have to. The feeling is in the framing: the easy tempo, the precise geometry of twang and space, the way everything leaves room for a decision that hasn’t been made yet but already feels inevitable.

The recording dates to 1965, from Strangers, Haggard’s debut on Capitol after the Tally era, co-produced by Ken Nelson and Fuzzy Owen. It’s early days in a career that will soon redefine West Coast country, and you can hear the pivot: Bakersfield grit, tidy and road-hardened, being carried through a major-label door without losing its dust. If you map Haggard’s arc, this is the stretch where the California honky-tonk he cut his teeth on becomes exportable—still lean, still lived-in, but tuned to travel. The track sequence places “Falling for You” near the top, a modest-sized cut that acts like a thesis statement: economy, everyday poetry, emotional straight talk.

A word about authorship. “Falling for You” is credited to Ralph Mooney—the pedal-steel ace whose writing and playing helped codify the Bakersfield vocabulary. That matters. Mooney’s lines don’t just decorate; they narrate. His steel moves like a second voice, harmonizing with Haggard’s baritone even when the singer stops to breathe. The difference between “sad” and “resigned,” between “hope” and “risk,” often lives in those half-steps. You can hear it here: a lingering pull, a delicate return to tonic, a brief hover that says the heart hasn’t quite signed the contract.

Zoom out to the band picture and another piece clicks. The Strangers—Haggard’s road unit—are the sort of musicians who make invisibility into an art. Roy Nichols plays lead with that unmistakable Bakersfield snap, his guitar notes quick and articulate, like chisel marks on soft pine. Ralph Mooney’s pedal steel is the velvet knife. George French Jr.’s piano comps lightly in the midrange, never crowding the vocal, often carrying the harmony that the steel leaves suspended. Name the ingredients and you might expect flash; Haggard and company choose contour instead. It’s the shape of the room, not the neon sign.

“Falling for You” is not a showpiece. It’s a study in controlled pressure. The drummer keeps that two-step pulse so even you could check your watch against it. The bass is a floorboard, firm but springy. When Haggard enters, the mic captures him a touch forward—dry, local, honest. There’s little reverb on the voice; the air around him feels like a real space, not a glossy warehouse. Listen for the way he rounds off the ends of phrases, saving the slight lift for the clause that contains the verdict. You don’t need a high-drama bridge when the bridge is the distance between what you should do and what you’ve started doing anyway.

Here’s the heart of it: Haggard’s early singing is practical, almost architectural. He lays beam upon beam—consonants you can count, vowels that stretch but never drip. It’s the plainspokenness that turns into poetry on the third listen. By the second chorus, the band tightens a fraction, like a hand closing politely but firmly around the idea. The steel makes one of those smiling-through-tears glissandos, Nichols throws a tidy answer lick, and the melody gives you the generosity you came for. The song ends without fanfare and leaves behind a small crater.

What kind of piece of music is this? It’s one that leaves you in possession of a little more honesty than you had before. The lyric’s premise—risking a fall you half-hope will happen—could tilt either way. But the performance keeps it grounded, democratic even. This isn’t a cinematic confession from a mountaintop. It’s a quiet yes said at a kitchen table, late, when the clock is the only loud thing in the room.

Strangers, the album, is full of early markers: “(My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers,” “Please Mr. D.J.,” “You Don’t Have Far to Go,” the Wynn Stewart carry-over “Sing a Sad Song.” Hearing “Falling for You” in that company shows you the range Haggard was framing even at the start—roadhouse tempos, torchy slow dances, the unadorned ache of songs that don’t try to be bigger than the rooms they were written for. The LP would go top-10 on the country albums chart, but the deeper significance is stylistic: a West Coast sensibility that refused to polish off the fingerprints.

Micro-story No. 1: Years ago I DJ’d a small bar where couples actually danced—boots, belts, the whole clatter. Put on “Falling for You” after a run of fast numbers and the floor changed texture. People moved closer. Shoulders rose and fell. Two minutes and a few seconds later, they walked back to their tables looking as if they’d negotiated something—maybe not solved it, but named it. That’s the kind of song this is, a hinge cut. It turns a room just enough.

Micro-story No. 2: I tried the track through a pair of studio headphones one night, midnight volume, no distractions. The steel’s sustain felt almost tactile, like touching the rim of a glass and feeling it sing. The vocal sits near center, but you can pick out the guitar’s little side-smiles left of the stereo field, the way the piano anchors a middle shelf that keeps the whole structure from tipping. The more you zoom in, the more you admire how little anyone tries to steal a scene.

Micro-story No. 3: A friend of mine who swears he can’t stand “old country” kept this one on a driving playlist, slotted between modern Americana and a 1990s alt-folk track. It never blinked. Some recordings make genre a topic sentence. This one makes feeling the grammar.

If you’re new to Haggard, a little context helps. Capitol’s Ken Nelson had an ear for letting artists be who they were and capturing why that self would travel. Fuzzy Owen—longtime advocate, co-producer, manager—understood how to keep a working band’s character intact even as budgets and reach changed. Strangers is the sound of those hands off the wheel just enough. And while many sessions of the era got sweetened with strings, the Bakersfield backbone stayed visible here: Telecasters, pedal steel, dance-floor math. You can hear the heritage, and you can hear the ambition.

“The difference between modest and unforgettable,” I wrote in my notes, “is often a single performance choice held with discipline.”

“Falling for You” is full of those choices. The tempo never drags, but it never hurries. The vocal refuses melodrama; the band refuses filler. Even the steel’s prettiest curlicue draws a map back to the line you’re supposed to hear next. When Nichols takes a tiny turnaround, it’s not to impress you; it’s to escort you across the bar to the chair you’ve been avoiding. And the ending—clean, untelegraphed—feels like the lights going up just enough to see that nothing outward has changed, though you know something inward has.

We should talk a little about tone, because Bakersfield records often get simplified to “loud Telecasters and barstools.” That’s not wrong, but it’s incomplete. This cut is about touch. The pick attack is clipped but not harsh. The steel’s vibrato is narrow, almost a whisper. The drum sound is close, with the snare’s wires clearly speaking under light sticks. It’s the kind of recording that makes you aware of distance: mouth to mic, pick to string, pedal to string. If you listen at conversational levels on a decent home audio setup, you can sense the air stir when the band leans into a chorus—and then backs off like courteous guests.

Does it belong to one emotional color? Not really. Haggard’s early catalog is full of mixed weathers, and this one carries the after-rain smell of a decision you’ll be living with in the morning. The narrator knows the risk. He won’t declaim it. He embodies it. Where later, larger singles would put architecture around heartbreak—bigger hooks, starker narratives—this track uses the least lumber for the most shelter.

As a critic, I’m supposed to identify the grand takeaway, the career-sized thesis. Here’s mine: Haggard found greatness early not by writing the biggest story, but by trusting the smallest details. The specific breath before a confession. The steel line that bends one extra millimeter. The band that treats a dance floor like a place where lives are negotiated in public. That’s why “Falling for You,” a sub-three-minute B-side feeling of a tune, keeps revealing itself decades later. You don’t outgrow it because you didn’t exhaust it on first contact.

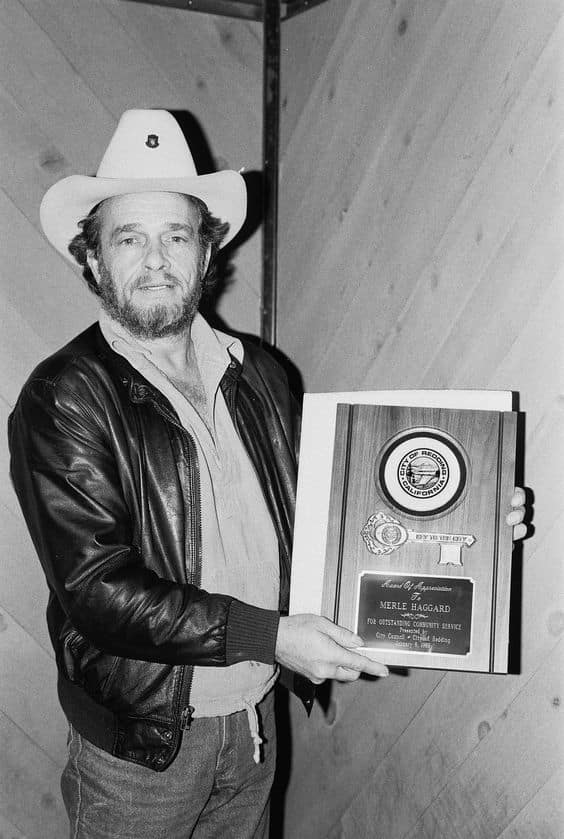

Let’s also be precise about provenance. The YouTube track making the rounds is the remastered edition tied to later reissues, but the original cut belongs to 1965, announced to the world on Strangers, a Capitol record whose personnel and producers are well-documented. Strangers climbed into the country chart’s upper tier, and it seeded a run of releases that would make Haggard the genre’s essential narrator for the next decade. The fact-trail matters not to fetishize data, but to honor how this small song sat at the start of a very big road.

One last listen. This time I focus on the relationship between steel and voice. The steel never quite doubles the melody; it trails, nudges, or pre-echoes it. That dance creates the sense that the singer’s thoughts are happening half a second ahead and half a second behind his words. You believe him not because he strains to prove sincerity, but because the band’s phrasing proves he’s not alone. It’s a communal honesty—the kind that can only happen when players absorb a song’s temperature together and keep it there.

As for mechanics: the mix places the instruments with surgical calm. Nothing jumps, but everything glows. The midrange—where human attention lives—is rendered with care. You could diagram the spectral balance and it would look like a conversation around a table. These choices make “Falling for You” portable across eras and equipment. It works in a truck, in a bar, and in the kind of quiet room where you can hear your own second thoughts.

And that, to me, is why this track endures. It’s not rare because it’s flashy. It’s rare because it’s useful. It gives shape to the ordinary drama of deciding to let yourself be moved. It respects the listener by declining to pretend that decision is easy. In a catalog that would later contain towering anthems and award-night signatures, “Falling for You” remains the spare wooden chair that you keep pulling back to the table.

If you want the official paper trail, Strangers is the album to start with. If you want the field guide, “Falling for You” is the page you dog-ear. Play it next to the rowdier tracks; it will hold. Play it next to torch standards; it will make them tell the truth. That’s the miracle of constraint. It doesn’t limit feeling; it frames it.

Before I close, a practical note for listeners who like to compare masters: the remastered versions floating around on digital platforms are clean without sanding off the fundamental character. The steel still breathes, the vocal still feels close-miked, the rhythm section still sounds like a band that could pack up in ten minutes and make their next show two towns over. Put it on, let the tempo set your heartbeat, and notice how the last line leaves you a little suspended—exactly where the song wants you.

“Falling for You” doesn’t ask to be your favorite. It asks to be there when you need a song that tells the truth as gently as possible.