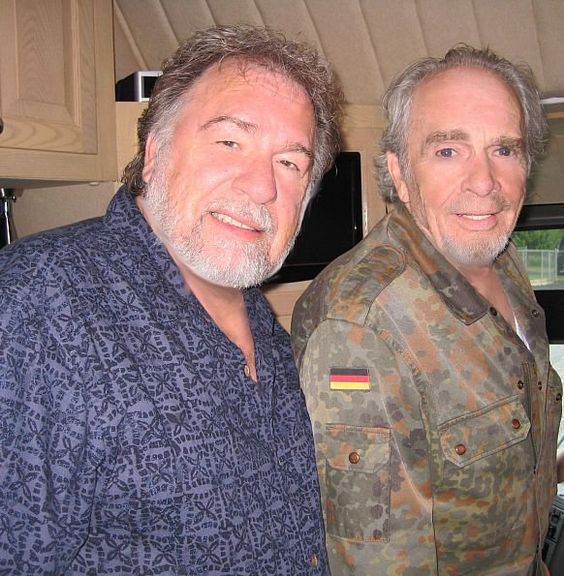

It begins not with a blare, but with a palpable sense of duty. An almost reverential hush precedes the first notes, setting the stage for a piece of music that is less a casual listen and more a declaration. Gene Watson, the “Singer’s Singer,” approaches Merle Haggard’s seminal 1970 anthem, “The Fightin’ Side of Me,” not as a cover, but as a commitment—a renewed pledge to the classic country sound he has championed for decades.

For listeners steeped in the glamour of modern country, stepping back into a Watson recording is like trading a stadium spectacle for a smoke-filled honky-tonk stage, the kind where every note has weight and every word is etched in grit. Watson’s career, launched nationally in 1975 with the Capitol Records hit “Love in the Hot Afternoon,” is a tapestry woven with heartbreaking ballads and assertive traditionalist fare. This song, in particular, often appears in the later chapters of his vast discography, frequently on live recordings or compilations, serving as a powerful nod to his influences and his core audience’s values. It’s a recurring theme in his body of work: a deep respect for the roots and writers who paved the way.

🎸 The Anatomy of a Country Classic

The power of this rendition lies entirely in its restraint and its unwavering focus on the core message. Merle Haggard’s original was a potent cultural artifact, a working-class response to the anti-war movement, and Watson treats that legacy with a craftsman’s care. The arrangement is archetypal country: a classic rhythm section, a crisp, driving acoustic guitar, and the shimmering lament of the pedal steel.

The sonic texture is clean, almost spare, allowing Watson’s voice to sit front and center, mic’d close enough that you can hear the subtle catch in his breath, the slight Southern burr on certain vowels. There’s a noticeable lack of heavy compression, which helps preserve the natural dynamic range—a quality that rewards listeners who invest in premium audio equipment. The mix favors clarity over flash, a deliberate choice that makes the assertion of the lyrics land with maximum impact.

The instrumentation creates a sturdy, unyielding frame. The bass line walks with deliberate certainty, anchoring the tempo, while the drums are played with a simple, unfussy pocket rhythm. The lead guitar parts, often played on a telecaster or similar bright-toned electric instrument, cut through with short, melodic fills that echo the phrasing of a fiddle or a steel guitar. Crucially, the piano, when present, functions as a textural cushion, offering chords that fill the mid-range without ever competing with the vocals or the steel’s sustained notes. It is a masterclass in how much can be conveyed with few moving parts, a testament to the enduring simplicity of the honky-tonk band.

📜 Lyrical Heritage and The Singer’s Delivery

The song’s lyric, penned by Haggard, is a straightforward defense of a certain kind of American working-class patriotism, a rebuttal to those who criticize the nation while “living in the land of the free.” When Watson sings these words, he does so with a distinct lack of theatrics. He doesn’t bellow or rant; his delivery is firm, measured, and deeply convincing.

“The best way to keep from speaking your mind

Is to keep your mouth shut most of the time.”

That line is delivered with a kind of weary wisdom, suggesting a man who has held his tongue many times, but who feels compelled now to speak. It’s the contrast between his normally velvety tone and the abrupt, hard edge he introduces here that makes the performance so captivating. Watson’s strength has always been his peerless ability to navigate an octave with smooth, seamless transitions, but here he sacrifices some of that vocal grace for raw, undeniable authenticity.

This isn’t merely a political song; it’s a statement of identity. For the listener, it conjures the image of a dimly lit diner counter or a worn vinyl booth, the kind of place where men and women who feel unheard finally find a voice in the jukebox. It’s the sound of a conviction held deep in the chest, given sudden, soaring expression.

“The singer is not just performing; he is translating the sentiment of a generation that felt misunderstood.”

It is a powerful example of how an album track or a compilation deep cut can resonate years after its initial popularity, simply because the artist brings a new layer of lived-in experience to the material. When you listen with a set of good studio headphones, the clarity of the arrangement is startling; every pick stroke and pedal steel bend feels intentional, serving the song and the emotion, not just the technical prowess.

The track reinforces Watson’s standing not just as a hitmaker, but as a staunch preservationist of country music’s most profound and straightforward storytelling tradition. The commitment to his vocal style, which never chases fleeting trends, is a major reason why this decades-old piece of music still connects with modern audiences seeking genuine roots country. The emotional truth in his phrasing—the slight lift on a high note, the quick, clean vibrato on the word “flag”—transcends the time and politics of the original release.

The truth is, while many come to Watson for his ballads, they stay because his artistry is fundamentally honest. He represents a kind of country music that is simple, direct, and overwhelmingly powerful—the very same reasons Haggard’s composition endures. Re-listening to this track, one is reminded that the greatest voices don’t just hit the notes; they inhabit the entire world of the song.

🎶 Similar Sounds for the Traditionalist Ear

- Merle Haggard – “Okie From Muskogee”: The spiritual and thematic precursor, addressing the same cultural moment with direct, unapologetic language.

- George Jones – “The Grand Tour”: A contrasting mood (deep heartache), but shares the traditional instrumentation and a commitment to raw vocal storytelling.

- Conway Twitty – “Hello Darlin'”: Similar mid-tempo pacing and use of a prominent, emotional vocal delivery, a true “singer’s singer” performance.

- Keith Whitley – “Don’t Close Your Eyes”: An essential ’80s track that retained the classic country feel, showcasing vocal purity and traditional arrangement prowess.

- Hank Williams Jr. – “A Country Boy Can Survive”: A later song that channels the same spirit of cultural defense and self-reliance, with a similarly driving rhythm.

- Dwight Yoakam – “Guitars, Cadillacs”: Excellent example of the post-Haggard Bakersfield sound, emphasizing the role of the acoustic and electric guitar in the rhythm section.