The year is 1965. The air is thick with a strange brew of optimism and impending fracture. Pop music is speeding toward an electric, psychedelic horizon, yet one of the year’s most enduring anthems arrives wrapped in the stately, shimmering elegance of a Burt Bacharach arrangement. This is the curious, contradictory power of Jackie DeShannon’s defining hit, “What The World Needs Now Is Love.”

I first encountered this song not on vinyl, but in a memory-scene painted by weak FM radio static during a long, late-night drive across a deserted stretch of highway. The tune floated out, instantly recognizable, but stripped of its usual cheerful context. It felt heavier, almost mournful, the sheer weight of its simple request pressing down on the silence of the car.

That initial feeling—of a deeply felt ache beneath a polished surface—is the key to understanding DeShannon’s definitive version. It’s an unusual piece of music in the pop canon. It does not demand; it simply observes a fundamental human deficit and offers an elegant solution.

A Voice Against the Tide

Jackie DeShannon was already a force in the music industry by 1965, though often behind the scenes. She was a prolific songwriter, penning hits for The Searchers (“When You Walk in the Room”) and others. Her career arc placed her perfectly at the nexus of the ’60s folk revival and the orchestrated pop coming out of the Brill Building. She had grit and a distinct Southern vocal texture, but also an innate pop sensibility.

“What The World Needs Now Is Love” was, famously, initially rejected by Dionne Warwick, who reportedly felt its message was too simplistic for her complex artistic collaborations with the Bacharach/David team. It fell to DeShannon, and what she brought to the table was exactly the humility the lyrics required.

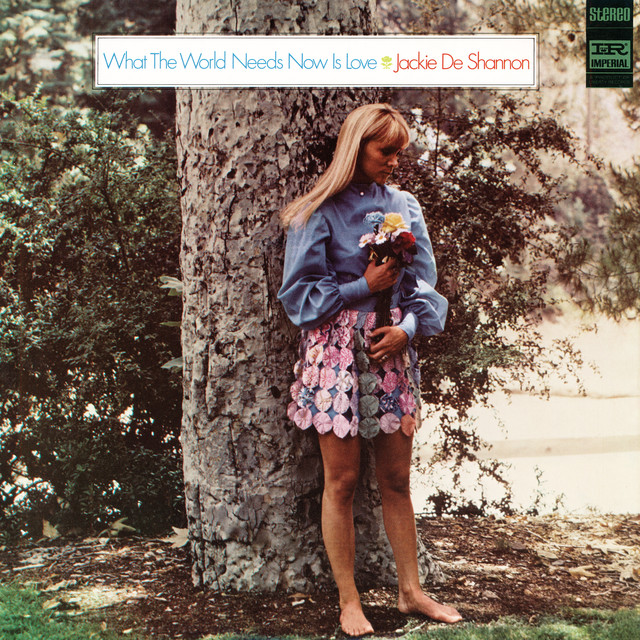

The single, released on the Imperial Records label, was featured as the opening track on her 1965 album, This Is Jackie DeShannon. It was produced and arranged by the composer himself, Burt Bacharach, in collaboration with lyricist Hal David. This pairing ensured the track was imbued with the sophisticated, almost cinematic scope that defined the Bacharach sound.

The Architecture of Affection

The brilliance of the arrangement lies in its restraint, especially given the song’s grand, universal theme. The track begins with the stark, insistent, and slightly melancholy signature figure played on the piano. It establishes the unusual meter—a shifting, almost waltzing rhythm—that keeps the listener slightly off-balance, reflecting the unease of the era.

DeShannon’s vocal delivery is startlingly direct. She navigates the complex, unexpected chord changes—the very hallmark of Bacharach’s composition—with an unadorned, almost matter-of-fact tone. There is no histrionics here. When she sings the title phrase, it sounds less like a rousing call to action and more like a shared, weary secret. The sound of the recording itself feels surprisingly intimate, almost as if she is singing directly into a slightly warm, older-style microphone.

The guitar in the arrangement is subtle, providing gentle fills and texture rather than driving the rhythm. It often doubles the string figures, adding a woody, acoustic warmth beneath the vast canvas of the orchestration. The percussion is delicate, mainly cymbals and brushed snare, building the tension slowly.

In fact, the true engine of the song’s emotion is the string section. They swell and recede in perfect dramatic arcs, never overwhelming the vocalist. At the two-minute mark, just as DeShannon hits the bridge, the dynamics shift. The backing vocals, reportedly featuring Cissy Houston, enter with a gentle power, turning a personal plea into a communal declaration. This is where the emotional catharsis arrives, a moment of expansive warmth that makes the preceding restraint all the more impactful.

The Hard Truth of Soft Sound

The song peaked within the top ten of the US Hot 100 chart, a solid success that solidified DeShannon’s reputation as both a writer and a formidable interpreter. It landed in a cultural moment when grand statements were being traded for intimate, individual appeals. The message—that “love, sweet love” is the ultimate necessity, transcending physical and material needs—was radical in its simplicity, a stark contrast to the escalating international conflicts of the time.

Consider the line: “Lord, we don’t need another mountain, there are mountains and hillsides enough to climb.” David’s lyricism here avoids platitude; it speaks of physical exhaustion and existential fatigue. It’s a beautifully concise piece of writing. Even today, if you play this song through a high-quality set of premium audio speakers, the subtle complexity of the string arrangement reveals itself, showcasing Bacharach’s meticulous hand. It’s not a simple pop song; it’s a chamber piece of music dressed in rhythm section clothes.

“The song’s power is not in its volume, but in its quiet, confident refusal to give up on its central, unshakeable belief.”

I think of a friend, an overworked public defender, who plays this song every Friday afternoon as he clocks out. For him, the song is a ritual, a reminder of the foundational decency that must underpin his exhausting work. It’s not just an anthem for global peace; it’s a soundtrack for the personal, daily struggle to remain empathetic. Similarly, I know a young musician just starting out, learning to transpose older pop structures. He keeps a copy of the sheet music for this particular track, studying the counter-melodies between the bass line and the vocal phrasing, absorbing the lessons in sophisticated pop writing.

The piano continues to be the backbone, its chords the foundational stone of the entire structure. The final moments of the track fade out, leaving the strings to gently dissolve. It’s a conclusion that suggests the question—What the world needs now?—will remain open, and the answer—Love, sweet love—is a perpetual choice, not a single, dramatic arrival.

It is this mixture of glamour and grit, of orchestral sweep tethered to a raw, honest vocal, that makes DeShannon’s recording irreplaceable. It is an artifact of a specific time, yet its message is utterly timeless. It invites us not to sing along mindlessly, but to quietly reflect on the cost of our current deficits and the profound beauty of human connection.

Listening Recommendations

- “Anyone Who Had a Heart” – Dionne Warwick (1963): For a masterclass in how Bacharach/David tailor complex arrangements to a singular voice.

- “Put a Little Love in Your Heart” – Jackie DeShannon (1969): Another self-penned classic by DeShannon that carries forward the optimistic, humanist theme.

- “Up Up and Away” – The 5th Dimension (1967): Shares a similar airy, orchestral pop production and themes of hopeful escapism in the late ’60s.

- “Wichita Lineman” – Glen Campbell (1968): Features Jimmy Webb’s equally sophisticated, wide-screen arrangement that balances melancholy with melodic strength.

- “Alfie” – Cilla Black (1966): A different Bacharach/David classic, showcasing a similar vocal restraint against lush, building orchestration.

- “Hurt So Bad” – Little Anthony & The Imperials (1964): An excellent example of a soaring, dramatic mid-60s pop track that uses strings to magnify emotional depth.