I remember the first time I heard it—not as a blast of nostalgia on an oldies station, but as a disruptive anomaly, a two-minute piece of music that seemed to defy the smooth, choreographed sound of the radio dial. It was late, maybe two in the morning, and the static-laced airwaves yielded a noise that felt less like pop song and more like a tribal instruction manual for pure, unadulterated rock and roll.

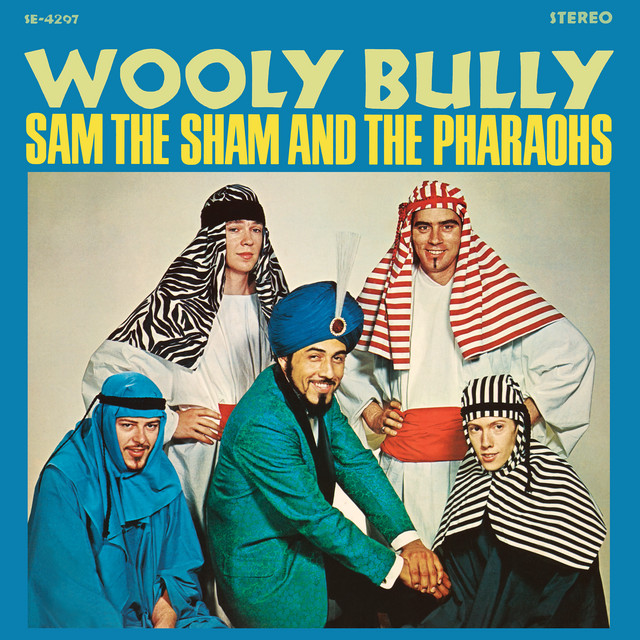

The countdown begins in Spanglish, a command shouted into the dark: “Uno, dos… one, two, tres, cuatro!” It’s the sound of a garage door rolling up on an American basement scene, immediately transporting you to a moment of spontaneous, slightly drunken genius. This wasn’t the manicured pop landscape of 1965; this was Sam the Sham & The Pharaohs arriving like an uninvited guest to a white-glove party, wearing a turban and driving a hearse.

The song is, of course, “Wooly Bully,” the worldwide smash that launched Domingo “Sam” Samudio and his band onto the international stage. Released initially as a single in late 1964 and then reissued by MGM in 1965, the track became the anchor and namesake for their debut album, Wooly Bully, later that year. Its success was a cultural earthquake, a homegrown Memphis sound—filtered through Samudio’s Texas roots and love of Latin rhythm—that managed to sell a million copies domestically right in the teeth of the British Invasion. It was, many sources note, the ultimate American counterpunch.

The Gritty Anatomy of a Hit

What makes this track a timeless piece of music is its brilliant, almost accidental minimalism. Stan Kesler, a veteran of the Sun Records orbit, reportedly handled the production at Sam C. Phillips Recording Studio (Phillips’ second Memphis location), and the sound is beautifully raw. There’s little polish, only urgency.

The bedrock of the song is the rhythm section: drummer Jerry Patterson delivers a simple, insistent backbeat, while David A. Martin’s bass guitar anchors the frantic energy with a driving, repeating line. It’s a 12-bar blues progression, but treated with a kind of reckless abandon. This structure is not a formal blueprint; it’s a skeleton for a party.

Then there is the instrumental star: Samudio’s own Farfisa organ. It’s the song’s signature texture, a thin, buzzing, trebly riff that cuts through the mix like a cheap serrated knife. It’s a sound that would define much of the era’s garage rock—the sound of budget and brilliance colliding. This small, crucial electronic piano sound is what elevates the track from a blues stomp to an instantly recognizable global anthem. The way that organ buzzes, almost fighting against the rhythm, creates the song’s inherent tension.

Ray Stinnett’s guitar work is economical, mostly providing rhythm chugs and color, stepping forward only for the simplest, most effective riff work. The true instrumental solo, however, belongs to Butch Gibson on the saxophone. It’s a frantic, honking blast of R&B energy, perfectly matching the overall air of barely-controlled mayhem. The entire arrangement is a masterclass in ‘less is more,’ clocked in at a lean two minutes and twenty seconds. The brevity is part of the genius; it hits you, makes you dance, and vanishes before you can ask what the lyrics meant.

The Sound and the Story

The lyrical content, a simple narrative about two characters named Matty and Hatty and a mysterious creature called the “Wooly Bully,” is notoriously ambiguous. Samudio’s slurred, shouted vocal delivery makes the words almost secondary to the rhythm. This vagueness, this impressionistic storytelling, reportedly led to the song being banned by some radio programmers who suspected the unintelligible lines were risqué. If you are listening on premium audio equipment today, you can discern the words, but in the gritty, compressed mono of a 1965 AM radio broadcast, it became a wonderful Rorschach test for youthful rebellion.

The shouts, the “Watch it now, watch it now, here he come!” interjections—they are primal. They give the song a call-and-response feel that ties it directly to the foundational rhythm and blues and early rock traditions, but injected with a distinctly Tex-Mex flair. The subtle, churning energy comes from Samudio embracing his heritage, fusing rock and roll’s energy with the borderland’s conjunto rhythms.

“The greatest hits often aren’t perfect recordings, they are simply perfect moments captured on tape.”

This cultural moment of ’65 was defined by a transition—from the polished teen idols to the rougher, self-contained band unit. “Wooly Bully” was one of the key American tracks that proved you didn’t need a huge budget or a symphonic arrangement to dominate the charts. You just needed an undeniable, three-chord hook. Today, it’s the kind of sound a serious musician studies after taking guitar lessons, realizing the real lesson is how to maximize impact with the fewest possible notes.

A Legacy of Grin and Grit

The lasting appeal of “Wooly Bully” lies in its swaggering refusal to be tidy. It is joyous, reckless, and deeply authentic. It’s the sound of a band enjoying the sheer kinetic pleasure of making a glorious noise. It reached a chart peak of number two on the Billboard Hot 100, and while it was famously kept out of the top spot by The Beach Boys and The Supremes, Billboard named it their Number One song of the year for 1965 based on its sustained commercial performance. That unique distinction tells the real story: this song was not a flash in the pan; it was the soundtrack to a whole summer.

When you revisit this track, pay close attention to the frantic energy that never dips. It’s a constant, driving pulse. This simple, shouted anthem provided a template for the emerging garage-rock sound that swept the U.S., a sound that prized energy and attitude over technical complexity. It’s not just an old song; it’s a living document of an era’s spirit.

“Wooly Bully” is a reminder that the best music often comes from the margins, from artists who look and sound like nobody else, who disregard all the prevailing trends and simply drive. It’s a piece of raw, unforgettable pop art, one that still commands you to stand up and dance—or at least, to shout along to the gibberish.

Listening Recommendations

- “96 Tears” – ? and the Mysterians (1966): Shares the driving, trebly sound of the Farfisa organ as the central hook, defining the genre.

- “Hang On Sloopy” – The McCoys (1965): Another mid-sixties garage-rock anthem featuring simple, infectious melody and an unpolished vocal delivery.

- “I Fought the Law” – The Bobby Fuller Four (1966): Features similar raw production and a three-chord rock and roll structure rooted in Sam Phillips’ Memphis lineage.

- “Do Wah Diddy Diddy” – Manfred Mann (1964): An early, high-energy single that captures the simplicity and vocal interjections that make “Wooly Bully” so immediately engaging.

- “Louie Louie” – The Kingsmen (1963): The ultimate predecessor, sharing the deliberate lyrical ambiguity and raw, cheap production that became hallmarks of garage rock.