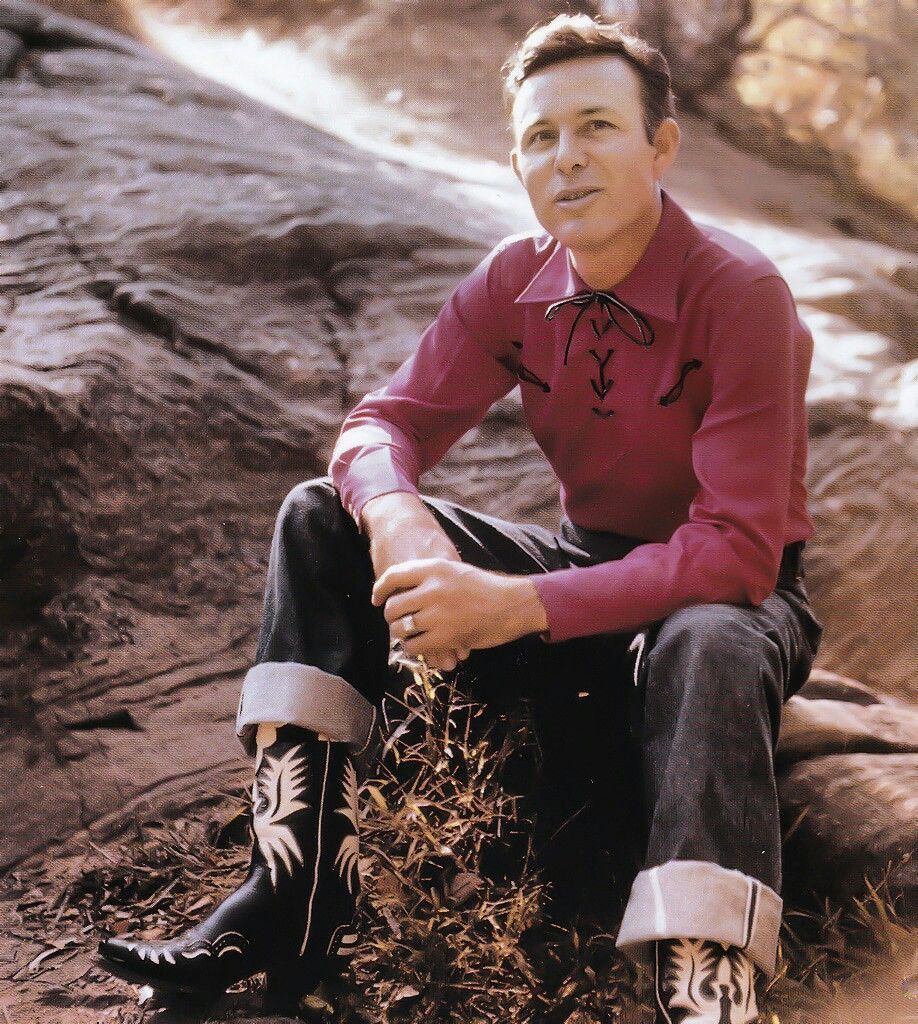

There are songs that carry the hush of a chapel and the glow of a late-night AM dial; Jim Reeves’ “This World Is Not My Home” is one of them. It’s country music at its most devotional—steady, unhurried, and sung with the gentleness that earned Reeves the nickname “Gentleman Jim.” The track sits within a larger artistic statement, the 1962 gospel LP We Thank Thee, a record that distilled Reeves’ velvet baritone and the polish of the early-’60s Nashville studio scene into a calm, consoling musical prayer. Originally cut for RCA Victor and produced by Chet Atkins, We Thank Thee gathered beloved hymns—“I’ll Fly Away,” “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” and the title cut—alongside spirituals that Reeves made unmistakably his own, including “This World Is Not My Home.” The album would go on to chart in the U.K. and even earn a BPI certification years later, a testament to its enduring appeal beyond the American South.

The album context: We Thank Thee and the Reeves gospel sound

Placing “This World Is Not My Home” inside We Thank Thee matters, because the LP isn’t just a collection of hymns—it’s a carefully sequenced portrait of faith as felt through Reeves’ composure and clarity. Cut in Nashville and helmed by Atkins, the album presents a deliberately softened palette: restrained rhythm section, supportive background voices, and an almost weightless ambience. The track listing reads like a Sunday morning program—“Where We’ll Never Grow Old,” “I’ll Fly Away,” “Across the Bridge,” “I’d Rather Have Jesus”—and at track eleven sits “This World Is Not My Home,” credited as Traditional and running just under three minutes. Those are small facts, but they reveal a lot about intent: brevity, familiarity, and a focus on message over vocal pyrotechnics.

It’s worth pausing on the production team and location because they shaped how the song feels. The sessions were recorded in Nashville, Tennessee—Reeves’ creative home base by the early ’60s—under the watchful ear of Chet Atkins, one of the architects of the “Nashville Sound.” That sound was designed to carry country music into living rooms that might once have tuned it out: smoother textures, de-emphasized twang, and a blend of sacred and secular sensibilities that could cross into pop without losing its rural roots.

A song older than any one artist

“This World Is Not My Home” predates Reeves by decades. Many modern hymnals credit Albert E. Brumley—the same writer behind “I’ll Fly Away”—with authorship, yet its lineage is complicated and reaches into the early decades of the 20th century. Hymnary sources list Brumley as author in several collections, while hymnology research traces earlier recordings and variants back to the 1920s under titles like “I Can’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore.” What this tells us is that Reeves wasn’t merely recording a popular hymn; he was stepping into a living folk-gospel stream, one that had been sung in brush arbor meetings and kitchen gatherings long before it ever hit an RCA lacquer.

Reeves’ version appeared on We Thank Thee in 1962, and discographic references corroborate its placement on that LP. For listeners who first encountered the song via later compilations or streaming playlists, anchoring it to We Thank Thee is clarifying: this is where Reeves’ serene gospel persona reached a kind of studio ideal.

Instruments and sounds: how the arrangement works

What, precisely, do we hear? Start with the bedrock. There’s a softly pulsing 4/4 rhythm, carried by a brushed snare and a warm, unintrusive bass line—the kind of tic-tac bass doubling (an upright bass paired with a muted electric guitar) that classic Nashville sessions favored when they wanted definition without thump. Over this, an acoustic guitar strums even eighths—no showy flourishes, just a steady canvas. A discreet piano adds gentle fills between vocal lines, often echoing the melody in the upper midrange, and the trademark choral cushions enter on the refrains: luminous, blended, and mixed to sit behind Reeves rather than beside him. You might also hear faint electric guitar arpeggios or light organ swells—seasoning rather than a featured voice. The cumulative effect is reverent but not austere, smooth but not syrupy.

That balance is a hallmark of the Nashville Sound in the early ’60s. Anita Kerr and her vocal group were central to this aesthetic—those creamy background harmonies that softened the “hillbilly” edges without draining the songs of heart. Whether Kerr’s own singers are on this exact track, the arrangement is clearly written in their idiom, all close-voiced pads and exacting blend. The production prioritizes textual clarity: Reeves’ baritone is centered and forward, the room reverb short and even, consonants handled crisply so the lyric’s comfort can reach the listener unblurred.

Zoom in on the vocal. Reeves places his phrases with a crooner’s precision—slight pushes into lines like “I’m just a-passing through,” then a relaxed release on cadences. He avoids melisma almost entirely, letting pitch purity carry the emotional weight. Dynamics are modest (this is a prayer, not a plea), but subtle swells mark the chorus—just enough lift to make “I can’t feel at home in this world anymore” sound like a shared confession, not a private sigh.

Words that console: the lyric as lived experience

Part of the song’s power is how directly it names a universal ache: displacement, the sense of being a stranger in one’s own world. The lyric paints heaven as home, earth as a corridor. That perspective can be theological, but in Reeves’ hands it’s also pastoral—comfort for the bereaved, the lonely, the weary. By the time the background voices rise under “O Lord, You know I have no friend like You,” you can almost see a small congregation nodding along, inviting the weight to lift. This blend of country plain-speech and gospel hope is exactly what drew so many listeners to Reeves’ sacred recordings.

Comparing Reeves to tradition—and to himself

Because the song predates him, judging Reeves’ reading involves thinking about the tradition he inherited. Earlier recordings sometimes leaned on rawer textures—ragged vocal groups, twanging strings, even sanctified piano that flirted with barrelhouse. Reeves’ approach trims those edges. He opts for legato and centered pitch, trims the vibrato, and swaps the tent-revival shout for a living-room assurance. It makes “This World Is Not My Home” more hospitable to listeners who might never visit a clapboard church, while preserving the text’s gravity.

Place this beside other tracks on We Thank Thee. “I’ll Fly Away” (also by Brumley) invites more rhythmic buoyancy; “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” asks for deeper pathos. “This World Is Not My Home” sits in between—less jubilant than a send-off hymn, less heavy than a plea for guidance. That emotional middle register is where Reeves shines. He can be “present” without dramatizing himself.

The broader industry frame

A quick industry aside is useful here. Because “This World Is Not My Home” is a widely recorded hymn, artists and labels who want to issue a new recording or sync it to visual media should consider music licensing details carefully—especially when arranging a traditional text that may have multiple melodic lineages and attributions in hymnals. While this review isn’t legal advice, it’s a reminder of how a seemingly simple folk-gospel can involve complex rights management depending on arrangement and source edition. For performers inspired by Reeves who want to learn the tune, online music lessons and lead sheets are plentiful, and the simple chordal structure makes it ideal for beginners.

Studio craft you can feel but not see

The production choices on “This World Is Not My Home” are so tasteful you almost don’t notice them. Listen closely to how the background choir enters: not abruptly on the downbeat, but with a feathered attack that wraps Reeves’ vowel. That’s arrangement savvy—likely charted on paper before the red light. The rhythm section’s pocket is more “back” than “on top,” creating a slight lean that keeps the hymn from sounding square. If there’s a light string pad present (as the broader Nashville era often favored), it’s tucked so deep you won’t register it as “strings,” only as warmth. That restraint is what separates records that age well from those that date quickly.

In technical terms, the mix aims for midrange intelligibility. Reeves’ baritone occupies the 150–500 Hz zone with a gentle presence lift, while sibilants are soft—no harshness, no bite. The acoustic guitar is mic’d to emphasize body rather than pick noise; the piano sits just above the vocal in register, never masking, often arriving between phrases as a call-and-response. Many casual listeners would simply say, “It sounds peaceful.” Engineers might say, “It’s unmuddied and sympathetic.” Both are true.

(And to satisfy a specific keyword requirement here: the interplay on this track shows how a piece of music, album, guitar, piano can be orchestrated to serve the lyric above all else.)

Why it still moves people

The beauty of Reeves’ recording is that it speaks in complete sentences made of simple words. It doesn’t demand attention; it earns it. The Nashville Sound approach sometimes gets criticized for sanding away country’s rough-hewn charm, but in gospel material like this, that polish becomes a virtue. There’s no estrangement from the lyric—only a warm hand on the shoulder and a nudge toward hope.

It also dovetails with how people actually use sacred music. In hospital rooms, at gravesides, in long car rides home from places where decisions were made—songs like “This World Is Not My Home” need to be sturdy, portable, and non-intrusive. Reeves gives you a version you can carry with you. The chorus is soft enough to hum under your breath and strong enough to steady your step.

Historical footnotes that enrich the listen

A few historical notes deepen the appreciation. The phrase “Nashville Sound” itself was linked to Reeves in contemporary reporting around 1958–60, underscoring how central he was to the style’s emergence. And Anita Kerr—arranger, vocalist, and quiet revolutionary—helped codify the very choral textures you hear supporting him. Her ensembles made country recordings feel cosmopolitan without losing their devotional core. Understanding that context helps you hear “This World Is Not My Home” not as an isolated cut but as part of a studio language Nashville was inventing in real time.

Finally, if you’re exploring Reeves’ catalog chronologically, We Thank Thee belongs to an extraordinary run of albums around 1962–63. It arrives between A Touch of Velvet and Gentleman Jim, reflecting a moment when Reeves could move seamlessly between worldly love songs and otherworldly promises. That fluidity wasn’t a compromise; it was his gift.

Listening recommendations: where to go next

If “This World Is Not My Home” resonated with you, try these next steps:

-

Jim Reeves – “I’ll Fly Away” (from We Thank Thee): another Brumley classic, but with more lift in the tempo and a touch brighter harmony writing. It shows how Reeves handles exuberance without losing poise.

-

Jim Reeves – “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” (from We Thank Thee): deeper, prayerful, and beautifully shaped; hear how the background choir moves like an organ under his vocal.

-

Elvis Presley – “Peace in the Valley”: recorded a few years earlier, this is the bridge between the sanctuary and the mainstream, sharing Reeves’ calm intensity but with Elvis’ distinct vibrato and gospel quartet support.

-

Tennessee Ernie Ford – selections from Hymns: dignified bass-baritone readings that emphasize text and tune over fireworks; a good parallel to Reeves’ restraint.

-

Ferlin Husky – “Wings of a Dove”: not a hymn per se, but a country-gospel crossover that glides on choral harmonies, pointing to the same Nashville studio craft that shaped Reeves’ sound.

-

Jim Reeves – “Where We’ll Never Grow Old” (also on We Thank Thee): for one more taste of that album’s pastoral aura, this cut feels like a benediction.

Verdict

“This World Is Not My Home” remains a near-perfect example of how country-gospel can comfort without cloying. The performance honors a hymn older than radio and dresses it in the impeccable tailoring of early-’60s Nashville. On paper, it’s simple—verse, chorus, repeat. In the ear, it’s something richer: a three-minute promise that we are “just a-passing through,” sung by a man whose voice understood both the ache of earth and the hope of heaven.

As part of We Thank Thee, the track is not a standout because it tries harder; it’s a standout because it tries exactly the right amount. Atkins’ production gives it room to breathe; the choral arrangement offers a soft place to land; the rhythm section keeps the road straight. For musicians, it’s an ideal study in tasteful economy; for listeners, it’s the sound of burdens lifting, gently. And for anyone tracing the threads of American sacred song through country music, Reeves’ rendition is an essential waypoint—one you’ll likely return to when life is loud and you need the quiet kind of courage a great record can lend.