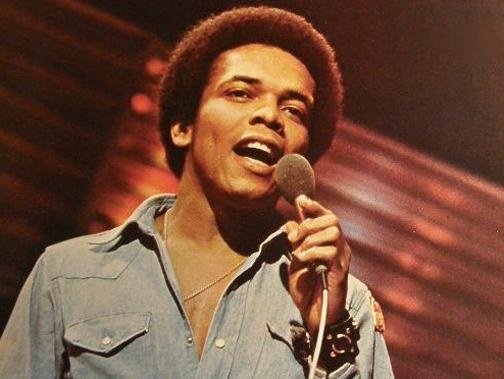

When Johnny Nash released “Tears On My Pillow (I Can’t Take It)” in 1975, he was already the rare American artist to have bridged U.S. pop, soul, and Jamaican reggae with effortless grace. This single completed that bridge for a British audience: it rose to No. 1 on the UK Singles Chart for the week of July 12, 1975—Nash’s only UK chart-topper—and it did so with a sound that was unmistakably reggae yet plush enough for mainstream radio. Just to clear the perennial confusion: Nash’s song is not the 1958 doo-wop classic by Little Anthony & The Imperials; his hit was penned by Jamaican songwriter Ernie Smith and produced by Nash with Federal Records founder Ken Khouri, arranged in a gently lilting lovers-rock style and even featuring a spoken monologue at its center.

The album: how the 1975 LP frames the single

The 1975 studio LP Tears on My Pillow gives the single a warm, cohesive home, and helps explain why the record feels so poised between island cadence and cosmopolitan polish. Issued on CBS (catalogue S 69148), the album surrounds the hit with a stylish, singer-forward set that folds in soul textures and reggae rhythms in equal measure. Its track list places “Tears on My Pillow (I Can’t Take It)” alongside a slate of smart choices and canny covers, including Bob Marley’s “Rock It Baby (Baby We’ve Got a Date),” and original material like “Why Did You Do It.” As an album statement, it presents Nash not just as the guy behind “I Can See Clearly Now,” but as a curator who could move with taste and authority through pop-soul and reggae-pop idioms. Contemporary discographic sources confirm the 1975 release and sequencing, and later reissues (notably in 1987 and the 2000s) kept the title in circulation for new listeners rediscovering Nash’s mid-’70s arc.

If you encounter a compilation or an international edition, don’t be surprised by alternate packaging; Nash’s catalog has been re-presented several times since the ’70s. But the core 1975 CBS LP remains the right context for hearing the single: it situates “Tears On My Pillow” inside a balanced set where the singer’s burnished baritone, his melodic instincts, and his affinity for Jamaican groove speak in a single voice.

How it sounds: rhythm, color, and the shine of mid-’70s production

Musically, “Tears On My Pillow” is a masterclass in restraint. The engine is a classic reggae one-drop feel: the kick and snare emphasize the third beat with a relaxed snap, while the bass walks a simple, hummable line that never fights the vocal. On the surface there’s the faintest shimmer: acoustic guitar upstrokes marking the offbeat “skank,” like a pendulum ticking time; a softly “bubbling” organ that fills the midrange; a few decorative piano touches to brighten cadences; and a veil of strings that thicken the chorus without smothering it. (Nash’s productions from this era often favored that stringed gloss—one reason his reggae crossovers landed so comfortably on adult-contemporary playlists.) The spoken interlude in the middle is pure theater: a quietly miked confession delivered as if directly to one person in a room, setting up the final chorus so the melody returns with a wash of recognition rather than a plea. These decisions—sparse rhythm section, vocal-forward mix, sympathetic strings—are why the track feels both intimate and immaculately finished.

Although detailed, session-by-session instrument rosters for the single remain sketchy, the credits are solid where it matters: written by Ernie Smith; produced by Johnny Nash and Ken Khouri; arranged and recorded in a reggae idiom that prioritizes groove and space. That combination of authorship and style is well-documented in contemporary and retrospective sources.

Nash the singer: phrasing, warmth, and a storyteller’s patience

What ultimately elevates “Tears On My Pillow” is Nash’s phrasing. He never oversings; he settles into the pocket and lets syllables ride the back of the beat, landing just behind the metronomic guitar strokes. On the chorus—“Tears on my pillow / pain in my heart”—he presses the vowel on “pain” with a slight lift, then releases it almost immediately, as if the confession is too tender to hold. In the verses, listen to how he rounds off consonants, sanding away sharp edges to match the track’s upholstered production. The speaking passage has a country balladeer’s plainspokenness—direct, earnest—but placed in a reggae setting, it acquires a conversational lightness that keeps the mood from turning maudlin. Nash’s gift is emotional modesty: he shows just enough to make you feel the hurt, never so much that it collapses into melodrama.

From a country & classical ear: familiarity inside a new groove

Hearing this as someone steeped in country storytelling and classical orchestration, the record’s balance is striking. The lyric’s directness—love lost, regret owned without self-pity—shares DNA with countless country laments. Meanwhile, the diaphanous string parts (often voiced in mid register, avoiding heavy vibrato) feel closer to chamber-pop than to reggae’s rawer ska roots. If you’ve spent any time with Nashville’s “countrypolitan” era—those Patsy Cline or Jim Reeves records where strings act as a halo around the voice—you’ll feel an immediate kinship here, even as the rhythm section gently rocks on a Kingston tide. It’s a reminder that elegant orchestration doesn’t belong to any one tradition; it’s simply a set of timbral choices, used here to present sorrow without heaviness.

At the same time, the arrangement remains rigorously reggae in its bones. The bass is the melody-carrier, the drum pattern enforces negative space, and the guitar is percussive punctuation. That marriage—countrypolitan sheen over a lovers-rock chassis—explains both the song’s crossover charm and its lasting replay value.

A brief note on provenance—and what it isn’t

Because the title overlaps with a famous doo-wop standard, it’s easy to misfile this single. Nash’s “Tears On My Pillow” traces back to Ernie Smith’s 1967 composition “I Can’t Take It,” recorded in Jamaica; Nash’s 1975 recording re-titled the song and shaped it into a lovers-rock crossover. The result was a new piece altogether, distinct in melody and authorship from the 1958 Little Anthony hit that Kylie Minogue later revived in 1990. That difference matters if you’re exploring lineages, playlists, or publishing history, and it’s amply documented.

Inside the mix: instruments and textures to listen for

-

Bass & drums: The one-drop groove anchors the emotion. Notice how the drummer often uses a rimshot on beat three to keep the pulse springy rather than heavy. The bassist, meanwhile, draws little melodic arcs that outline the chord movement; those arcs are what make the chorus feel like a gentle tide rather than a march.

-

Guitar & keys: The acoustic or lightly amplified guitar lives on the offbeat, but you’ll also hear tiny anticipations—sixteenth-note flickers that push the line forward. A warm electric piano or organ (“bubble”) smooths the harmonic floor, occasionally answering the vocal with a phrase that’s there and gone in a bar.

-

Strings: They’re mixed as a pad, not a lead—no syrupy countermelodies, just sustained chords that swell into downbeats. It’s a tactic drawn from pop balladry and classical texture-building, giving the track its satin sheen.

-

Voice as instrument: Nash’s soft-focus baritone acts like an additional string section, particularly in the double-tracked lines. Listen for the almost whispered breath before phrases in the middle eight; the production leaves that air in, giving the performance intimacy.

The net effect is a recording that rewards attentive listening on a good pair of speakers or reference headphones. If you’re evaluating audio services to hear it at its best, sampling on the best music streaming service you already use in high-resolution mode (or spinning a clean CBS pressing) will make those micro-dynamics and the tape warmth register vividly.

The LP’s ecosystem: how other tracks frame the mood

Part of what makes the single land is the way the LP curates adjacent moods. “Rock It Baby (Baby We’ve Got a Date)” nods to Nash’s ongoing conversation with Bob Marley’s songbook; “Why Did You Do It” and “I’m Comin’ Home in the Morning” broaden the palette toward Philly-soul and contemporary pop; elsewhere, tunes like “Reggae on Broadway” underline the cosmopolitan arc of Nash’s ’70s writing and production. Together they create a listening arc in which “Tears On My Pillow” becomes the tender, conversational midpoint—the emotional candela by which other colors on the album are measured. This sequencing is documented across discographic references for the 1975 release.

Songwriting and storytelling: the craft under the gloss

Ernie Smith’s lyric is deceptively simple: it speaks the plain truth of hurt without ornament. That plainness lets Nash, as interpreter-producer, do two clever things. First, he matches the text with a melody that barely leaps; when it does—on “pain in my heart”—the leap feels like a catch in the throat. Second, he frames the confession with an arrangement that breathes. Space equals sincerity here; the track trusts silence as much as sound. It is, in the most literal sense, a living “piece of music, album, guitar, piano.” Used sparingly, that quartet of words captures what’s happening: a song crafted as a discrete object, housed within an LP that cares about timbre, and carried by uncomplicated instruments you can picture in the room.

If you’re the sort who also tinkers with music production software, the record is a tutorial in doing more with less: high-passed guitars to keep the low end clean, strings tucked under a gentle compressor, and a vocal EQ’d for warmth rather than edge. The recipe is all about proportion, never spectacle.

Why it endures

Three things make “Tears On My Pillow” durable. First, Nash’s voice: it’s a humanely scaled instrument that avoids both vocal pyrotechnics and detached cool. Second, the groove: reggae’s heartbeat is there, but it’s swaddled in arrangements that invite listeners who might think they “don’t like reggae” to discover they do. Third, the cultural bridgework: by the mid-’70s, British listeners were primed for lovers-rock textures, and Nash—an American who had been cutting records in Jamaica since the late ’60s—knew exactly how to make that connection sing. The chart history and production credits tell this story in the record’s own metadata.

If you like this, cue these next

-

Johnny Nash – “I Can See Clearly Now” (1972). The inevitable companion piece: brighter, faster, and jubilant, with some of the same elegant string sweetening and rhythmic bounce that made Nash the era’s great reggae-pop emissary. The album of the same name, released in 1972 and featuring backing from Jamaican musicians, is a cornerstone in this crossover story.

-

Johnny Nash – “There Are More Questions Than Answers” (1972). Philosophical but feather-light; proof that Nash didn’t need a big hook to be memorable. Also from I Can See Clearly Now.

-

Ken Boothe – “Everything I Own” (1974). Lovers-rock royalty: a soul ballad rebuilt atop a reggae chassis, like Nash’s single but with a rawer vocal edge.

-

Jimmy Cliff – “Many Rivers to Cross” (1970). Gospel-tinted reggae with a stately organ and a vocal that reaches for the rafters; the ache in Nash’s single finds its cathedral here.

-

Bob Marley & The Wailers – “Stir It Up” (Nash’s cover or the Wailers’ version). A companion in feel and history—the connective tissue between Nash’s pop craft and Jamaica’s songwriting renaissance. Nash’s own relationship with Marley’s material is central to his ’70s output.

-

Janet Kay – “Silly Games” (1979). To hear where lovers-rock would travel later in the decade—lighter, higher, more overtly romantic—try this UK classic.

Final verdict

“Tears On My Pillow (I Can’t Take It)” endures because it is so exquisitely proportioned. Every element—the one-drop drum feel, the buoyant bass, the skanking guitar, the tender string pad, the shaded organ, and that quietly confiding voice—pulls in the same direction. It is a record about sorrow that refuses to be heavy, a ballad in which grace is the governing aesthetic. Within the 1975 album that shares its name, it becomes the emotional axis around which the set turns, a reminder that Johnny Nash’s gift was not just writing or singing but taste—saying enough, never too much, and trusting the listener to meet him in the space between beats.

For listeners who love country’s plainspoken truth and classical music’s textural finesse, Nash’s hit feels familiar on first contact and richer with every replay. It’s a small miracle: a heartfelt soliloquy delivered in three minutes and change, half-sung, half-spoken, carried by a rhythm that makes even the saddest heart nod along. And though the artist is rightly immortalized for a different mega-hit, this single—and the 1975 Tears on My Pillow LP that cradles it—shows why he mattered then and matters still: he knew how to invite the world into a reggae groove without sanding off its soul. The documentation of its chart triumph, authorship, and album home is clear; the feeling it gives is clearer still.