The air in the Sun Records studio was heavy with Memphis humidity and the faint aroma of ozone from Sam Phillips’s antiquated tube gear. It was 1955, and the world was accelerating toward a seismic shift, but inside that tiny room at 706 Union Avenue, a simpler, grittier kind of revolution was brewing. It wasn’t the frantic, unrestrained howl of early rock and roll, but something far more disciplined, relentless, and dark. That sound belonged to Johnny Cash, and its vehicle was his second single, “Folsom Prison Blues.”

We talk often about the legendary 1968 live recording, the one that turned a concert into a cultural moment and a statement on penal reform. But to truly understand the Man in Black, we must rewind to the genesis: this original 1955 recording, released on Sun Records with Sam Phillips producing. It was a standalone single, backed with “So Doggone Lonesome,” before being collected two years later on Cash’s debut album, Johnny Cash with His Hot and Blue Guitar!

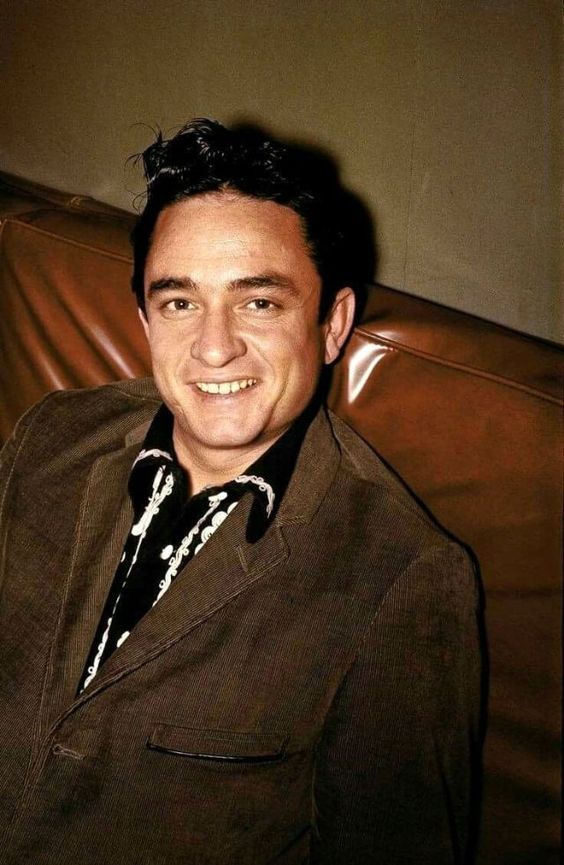

At this stage in his career, Cash was still a young man in the Air Force uniform who’d recently traded service for the siren call of country music. He and his band, The Tennessee Two—Luther Perkins on electric guitar and Marshall Grant on upright bass—were forging a new dialect. They were less a band than a rhythmic machine, a three-part harmony of stark, essential noise.

The production here, characteristic of Phillips’s work, is stripped-down, immediate, and completely unforgiving. There is no warmth of reverb, no sweetening string section, just the bone and sinew of the music. When we listen closely on premium audio equipment, the details of this sparse arrangement become visceral.

The Engine Room: Sound and Instrumentation

The true star of the original arrangement is what became known as the “boom-chicka-boom” rhythm, a sound that would define Cash for the next half-century. It is the sound of a train relentlessly grinding down a track, a perfect metaphor for confinement and the agonizing passage of time. This rhythm is generated not by a drummer—The Tennessee Two notoriously lacked one in the studio—but by Luther Perkins’s sharp, treble-heavy electric guitar.

Perkins holds a low, insistent, dampening tremolo riff that is less melody and more pure, percussive texture. It is a drone, a hypnotic pulse that drills into the listener. Cash himself also played a crucial rhythmic role, reportedly dampening his own acoustic guitar strings with a dollar bill to replicate a snare-like thwack on the off-beats. This ingenious hack gives the recording its unique, driving, yet entirely dry dynamic. It’s a sound that suggests not a party, but a work gang, a forced march.

The upright bass, expertly manned by Marshall Grant, provides a deep, woody underpinning, walking with solemn purpose. There is no melodic flourish, no improvisational jazz riffing, just a heavy, grounding anchor. The cumulative effect is one of restraint bordering on paranoia. It’s the sound of a man trapped in a concrete box, his only companion the distant, mocking sound of freedom embodied by the locomotive.

Cash’s vocal delivery is startlingly mature for a man so early in his career. His baritone is deep, steady, and chillingly devoid of self-pity. He doesn’t plead; he simply states his condition. His voice is placed front and center, almost unnervingly close to the microphone, lending the narrative an intimate, almost confessional quality.

“The economy of the 1955 recording cuts deeper than any orchestral swell, using just three instruments to conjure a lifetime of regret.”

The Cinematic Core: Narrative and Tone

The lyrics, of course, are what cemented this piece of music in the American consciousness. Cash, inspired by the film Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison and borrowing heavily from Gordon Jenkins’s “Crescent City Blues,” created a narrator whose moral compass is completely shattered.

“I shot a man in Reno / Just to watch him die.” It is one of the most infamously cold-blooded lines in all of popular song. What makes the lyric so potent is not the violence itself, but the narrator’s almost casual detachment, his utter lack of motive beyond pure, nihilistic observation. He has paid his debt, but his soul remains locked in a cage of his own making.

The narrator’s torment is not fear, but envy—envy of the rich folks eating and drinking on the passing train, their lives moving, while his own stands still. This contrast between the glamorous world outside the walls and the desperate monotony within is the core dramatic tension of the song. It taps into a primal human anxiety: the fear of being left behind.

Though the mood is unrelentingly dark, there is a strange, almost exhilarating energy in the guitar work. It moves so fast, so relentlessly, that it elevates the prison song into a rockabilly frenzy. The tempo is a desperate heartbeat, a furious pacing back and forth in a tiny cell. There is no time for a piano or complex melodic changes; the three members of the ensemble must simply keep the engine running, propelling the grim story forward.

The widespread success of this 1955 single, which peaked near the top of the Country & Western charts in early 1956, signaled that a massive audience was ready for Cash’s unvarnished truth. They recognized in his stark narrative a broader commentary on class, consequence, and the American dream gone sour. It was the first clear statement of the outlaw persona that he would carry, sometimes reluctantly, for the rest of his life. For those interested in learning to play this classic rhythm, a wealth of instructional guitar lessons exists, breaking down Luther Perkins’s deceptively simple, yet essential technique.

The Unending Echo

This 1955 recording remains a masterclass in musical minimalism. It proves that to convey a desolate world, you don’t need lush arrangements or studio trickery. You just need a strong voice, a heavy subject, and a rhythm that pulses like an inescapable doom.

This version is essential listening, a blueprint for American grit. When you put on the live 1968 version, you hear the catharsis, the release, the roaring crowd. But when you put on this 1955 studio original, you hear the quiet, claustrophobic despair—the true, cold sound of the walls closing in. It is a profound, foundational statement, one that rings just as true today for anyone caught in a cycle of regret.

Listening Recommendations (4–6 Similar Songs)

- “Sixteen Tons” – Tennessee Ernie Ford (1955): For the low-voiced, working-class narrative of inescapable economic and existential hardship from the same era.

- “That’s All Right” – Elvis Presley (1954): To hear Sam Phillips’s Sun Records recording philosophy—minimalist instrumentation, electric energy, and raw vocals—applied to a different kind of early rockabilly track.

- “Long Black Veil” – Lefty Frizzell (1959): Shares the somber, narrative-driven intensity and theme of tragic consequence, told from the perspective of the unjustly accused.

- “Hobo Bill’s Last Ride” – Hank Williams (1951): Connects to the ‘train song’ folk tradition and the theme of the lonely, forgotten man on the margins of society.

- “The Ballad of Jed Clampett” – Flatt & Scruggs (1962): A suggestion purely for the guitar technique—compare the speed and attack of Luther Perkins’s rhythm to Earl Scruggs’s bluegrass banjo roll, two masters of relentless forward momentum.

- “Cocaine Blues” – T.J. Arnall (Various recordings, popularized by Cash): Another prison song featuring dark humor, a grim narrative, and the fast, driving pace that defined Cash’s early repertoire.