The air in the room is thick, heavy with unspoken accusation and the scent of cheap perfume. It’s 1969, and the radio—if you were lucky enough to catch it between the day-glo psychedelia and the earnest folk revival—could suddenly deliver a punch of black-and-white, unvarnished human drama. That’s how “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town” hit the world: less like a song, more like the opening scene of a grim, independent film.

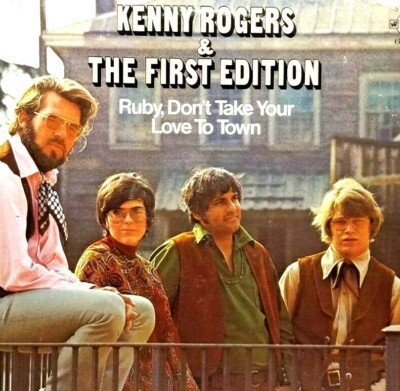

Before Kenny Rogers became The Gambler, the soft-focus balladeer with the perfect beard, he was the frontman for the genre-bending, slightly psychedelic outfit The First Edition. This single, a cover of a 1967 country song by Mel Tillis, was the turning point. It was the moment the billing on the record officially shifted to Kenny Rogers & The First Edition, cementing Rogers’s presence at the microphone and setting the template for the dramatic, narrative-driven country-pop that would define his solo superstardom.

Released in May 1969, the song became the title track for the corresponding album and was a massive international hit, reaching the Top 10 in both the US and the UK. It was a dark, brooding anomaly amidst a year of Woodstock dreams, demonstrating that the appetite for honest, heart-wrenching storytelling was as strong as ever.

A Vietnam-Era Tragedy, Two Wars Too Late

Mel Tillis, the songwriter, reportedly intended the narrative to be about a World War II veteran. However, the song’s reference to “that crazy Asian war” struck a raw nerve in 1969, instantly contextualizing it within the escalating tragedy of Vietnam. This ambiguity gave the already potent lyrics a terrifying, immediate relevance.

The song is a monologue, delivered from the perspective of an unnamed veteran, paralyzed and confined to his bed. He can only watch as his wife, Ruby, prepares to leave him nightly, presumably to find love and life elsewhere. The narrative is pure, escalating emotional torture, a claustrophobic vision of domestic disintegration.

The depth of the character study here is stunning. The narrator’s emasculation—“It’s hard to love a man whose legs are bent and paralysed”—is juxtaposed with his lingering, possessive love, which curdles into helpless resentment. This is not simply a sad song; it’s a portrait of a soul in crisis, trapped in a body that has betrayed him. The song is a masterful, three-minute cinematic tragedy.

The Sound of Desperation: Arrangement and Timbre

Produced by the team of Glen D. Hardin, Jimmy Bowen, and Mike Post, The First Edition’s rendition is a subtle marvel of arrangement. It straddles the line between their counter-culture roots and the country direction Rogers craved, resulting in a sound often dubbed “country-rock.”

The introduction is immediately arresting, anchored by the hypnotic, slightly menacing rhythm section. Terry Williams’ guitar work is restrained, offering a sparse, almost Spaghetti Western twang that cuts through the atmosphere like a razor. There is no triumphant solo, only nervous, repetitive figures.

Crucially, there is a pronounced lack of bright, acoustic piano. Instead, the harmonic backing is filled with dark-hued electric piano and possibly a harpsichord-like tone, creating a sound that feels both period-specific and timelessly stark. It’s a dry, intimate mix; you can feel the room around Kenny Rogers’s voice. The vocal delivery itself is the centerpiece of this piece of music. Rogers’s signature gravelly baritone, which would become instantly recognizable to the masses, is deployed here with masterful restraint.

He doesn’t belt; he whispers, pleads, and finally, collapses. The low register emphasizes the physical weight of his condition and the crushing emotional burden. His phrasing is conversational, almost a theatrical reading, right up until the chilling spoken-word climax: “Oh, Ruby, for God’s sake, turn around.”

The Craft of the Narrative: Dynamics and Delivery

The dynamic structure is key to the song’s power. It rarely rises above a mezzo-forte, relying instead on textural shifts to communicate tension. The drums, played by Mickey Jones, are often sparse, mostly emphasizing the downbeat, which creates a feeling of inevitable, slow-motion dread. The backing vocals from Thelma Camacho and Mary Arnold are used sparingly, a ghostly, ethereal echo that serves less as harmony and more as a Greek chorus of despair.

The central contrast lies in the lyrics versus the instrumentation. The verses are deeply sad, but the melodic structure is almost a waltz, a gentle, inexorable sway. This counterpoint—sadness dressed in a dance rhythm—heightens the tragic quality, suggesting a slow, formal surrender to fate. For those studying songwriting, or wanting guitar lessons in how to create dramatic tension without volume, this track is a masterclass in dynamic control.

In a small, contemporary vignette, I often recommend this track when people discuss songs about emotional captivity. We might not be paralyzed war veterans, but the feeling of watching something precious slip away, powerless to stop it, is universal. The song is a mirror for all those moments of quiet desperation that happen behind closed doors, away from the stadium lights.

“This is not simply a sad song; it’s a portrait of a soul in crisis, trapped in a body that has betrayed him.”

The success of Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town cemented the band’s commercial viability and pointed Rogers towards his future. It proved that his voice, full of warmth yet capable of delivering gut-punching dramatic realism, could bridge the gap between country storytelling and mainstream pop. It validated a direction that prioritized lyricism, character, and emotional depth over volume or flash, a gamble that paid off for Rogers for decades to come.

Listening Recommendations: Songs of Despair, Storytelling, and Genre Fusion

- Glen Campbell – “Wichita Lineman” (1968): A contemporary single that shares the same tone of bittersweet, adult melancholy and highly evocative lyrical detail, blending country and pop orchestration.

- The Doors – “Riders on the Storm” (1971): Uses the electric piano and a slow, almost cinematic sense of foreboding to create a dark, narrative atmosphere, similar to the tension in Ruby.

- Bobbie Gentry – “Ode to Billie Joe” (1967): A narrative classic that relies entirely on a single, compelling perspective and a sparse, atmospheric arrangement to tell a story of unspoken tragedy.

- Johnny Cash – “Folsom Prison Blues” (1955/1968): Shares the central theme of a man trapped and helpless, relying on a deeply resonant baritone vocal to convey the emotional core of the tragedy.

- Garth Brooks – “The Dance” (1990): A later country narrative hit that, like Ruby, uses a subdued, reflective delivery to explore a profound sense of loss and acceptance.