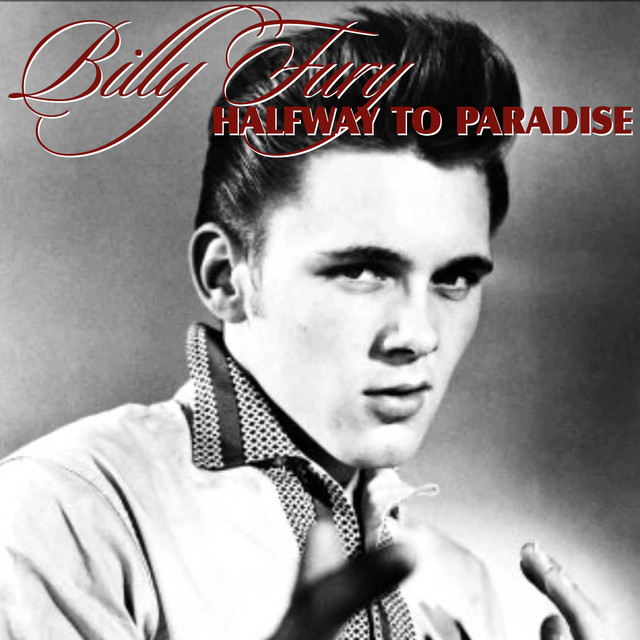

The year is 1961. The air in British music studios still felt like an echo chamber, holding the ghost of skiffle and the first, raw adrenaline of domestic rock and roll. Then, you had the crooners—the handsome boys who traded hip-shaking grit for satin-jacket polish. Among them, Billy Fury stood apart, a Liverpool working-class lad with the brooding intensity of a film star, but a voice capable of shattering vulnerability. His early singles, like the self-penned rockabilly brilliance of The Sound of Fury album, showed a raw, hungry artist.

But in the spring of 1961, everything changed. “Halfway To Paradise” arrived, a non-album single, a sweeping, dramatic cover of a Tony Orlando track. It was a conscious shift in his career arc, guided by Decca Records who sought to mold the rock and roll wildman into a sophisticated, chart-dominating balladeer, a British answer to Elvis Presley’s own transition to schmaltz and cinema. The single soared up the UK charts, becoming one of his biggest hits, peaking at number three. It was a turning point, sacrificing the raw guitar attack for a majestic, orchestrated sigh.

I often think of the recording session itself. Not the clinical, digital precision we know today, but a wide, deep room, packed with orchestral musicians, all looking toward conductor Ivor Raymonde. This was a major production for Decca at the time, a true leap into the lush, pre-Beatles baroque pop era. Raymonde, the arranger and conductor (with production credited to Dick Rowe and Mike Smith), understood exactly how to frame Fury’s voice—not with the standard four-piece band, but with an aural amphitheatre.

The Anatomy of Heartbreak: Sound and Instrumentation

The opening alone is a cinematic event. A dramatic, sweeping cascade of strings—violins soaring into their upper register—immediately announces the song’s grand, tragic scale. This isn’t background music; it’s the sound of a heart breaking on a grand staircase. The sense of drama is palpable, and for listeners today using studio headphones, the sheer depth of the orchestration is astonishing.

The core rhythm section is tight but often submerged beneath the symphonic swell. The drums keep a simple, purposeful beat, mostly accenting the downbeats with a heavy, yet tasteful, reverb tail that suggests the cavernous studio. The bass walks a subtle, resonant line. The piano, played with a classic, straight-eighth rhythm, functions primarily as a percussive anchor, holding the harmony firmly in place against the soaring strings. It provides a bright, stable counterpoint to the fluidity of the orchestral arrangement.

Fury’s vocal performance is the true centerpiece. He sings with a tightly controlled vibrato, his voice pushed forward in the mix, dry and immediate, conveying a potent mixture of teenage angst and wounded maturity. The control is remarkable; he holds back the sheer power of his instrument, opting instead for a wounded, breathy delivery on lines like, “And now you’ve gone, I’m only halfway to paradise.” It’s a masterful piece of phrasing, showcasing his ability to inhabit the persona of the romantic sufferer.

This piece of music, penned by the legendary American songwriting duo Carole King and Gerry Goffin, was fundamentally a Tin Pan Alley hit. But in Fury’s hands, and with Raymonde’s arrangement, it became something distinctly British and infinitely more melancholy. It traded American pop’s optimism for English pop’s innate sadness, achieving a glamour that was still grounded in rain-swept streets.

The Glamour and The Grit: A British Pop Paradox

Billy Fury always carried that contrast. He was handsome, charismatic, an original songwriter in his own right, yet here he was, delivering a polished, orchestrated cover, shedding his early rockabilly skin. It was a trade-off that elevated his chart career significantly throughout the early 1960s, making him one of the decade’s biggest domestic hit-makers—a fact often overlooked in the post-Beatles narrative.

The song’s success locked him into the role of the troubled romantic idol. This meant relinquishing creative control, shifting from his initial rock guitar focus to embracing the orchestral pop sound that audiences demanded. It was a Faustian bargain that defined the rest of his career, yielding a string of Top 20 singles but perhaps obscuring the raw talent of the artist he started as.

Think of a teenager hearing this on the radio in a dimly lit, smoky café. They are wrestling with the same melodramatic ache of young love. The song validated that feeling, treating their personal heartbreak with the dignity of a film score. It’s the sound of private agony made public, wrapped in the comforting luxury of a full string section.

“Billy Fury’s ‘Halfway To Paradise’ is not just a song; it’s a blueprint for the emotional blockbuster, where every heartache is scored with the majesty of a film soundtrack.”

This record holds a special place because it represents the pinnacle of that pre-Beatles, orchestrated sound, a moment right before the British music scene was detonated by bands who preferred four instruments to forty. To listen to “Halfway To Paradise” today is to witness the final, beautiful flourish of that era, a testament to what professional production and a captivating performer could achieve. It is a work of pop architecture—built to last, built to soar, and built entirely around the compelling vulnerability of its singer.

The popularity of this single was crucial in helping to finance and promote the eponymous album Halfway to Paradise, released later in 1961, which collected this hit alongside other singles and a mix of material. The track permanently established Fury’s vocal style and the lush arrangements that would characterize his peak years on the Decca label.

Listening Recommendations: Orchestral Pop and Teenage Drama

- Roy Orbison – “Crying” (1961): Shares the same dramatic, operatic vocal style and sweeping orchestral arrangement over a melancholic theme.

- Gene Pitney – “Town Without Pity” (1961): Another early 60s track that expertly uses big production and strings to amplify emotional torment and high drama.

- Mark Wynter – “Go Away Little Girl” (1962): Exemplifies the smooth, ballad-focused British pop of the early 60s that directly competed with Fury in the charts.

- Walker Brothers – “Make It Easy on Yourself” (1965): A later masterclass in the orchestral pop sound, featuring a deep, wounded baritone and soaring arrangement.

- The Everly Brothers – “Cathy’s Clown” (1960): Shares the vocal intensity and underlying heartbroken lyrical theme, though with a simpler arrangement.

- Joe Meek – “Telstar” (The Tornados) (1962): A sharp contrast, showing the simultaneous rise of instrumental futurism in British music around the same time period.

The music video below features the audio of Billy Fury’s enduring signature hit, “Halfway To Paradise.”

Halfway to Paradise — Billy Fury