The light in the café was always a bruised yellow, the kind of weak London winter light that seemed to promise nothing good, nothing permanent. I was seventeen, a vinyl enthusiast nursing a lukewarm cup of instant coffee, trying to make sense of the British folk revival’s dusty seriousness. Then, from the tired speaker tucked above the counter, a sound cut through the clatter of porcelain—a voice like spun sugar, high and impossibly clear, draped over a deceptively simple acoustic pattern. It was a purity that felt alien to the grittier folk singers I admired, yet it carried an ache that was immediately, profoundly recognizable.

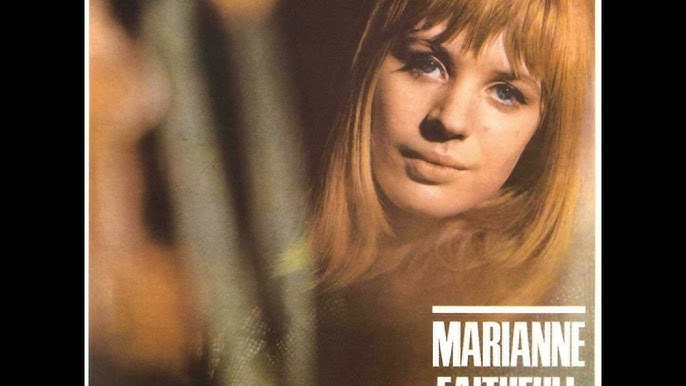

This was my introduction to Marianne Faithfull’s 1965 rendering of Malvina Reynolds’s protest hymn, “What Have They Done To The Rain.” It wasn’t the raucous, swaggering pop of her contemporaneous hits, nor the scorched-earth grit of her late-’70s resurrection. It was the sound of a fragile, aristocratic English Rose holding a political mirror up to the world, and it remains one of the most compelling pieces of music from her early career.

The Double-Bind of 1965: Pop Star vs. Folk Bard

To truly appreciate this track, you must first understand the conflicting gravitational pulls on Faithfull in 1965. Discovered by Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, she’d rocketed to fame with the Jagger/Richards ballad, “As Tears Go By.” Decca Records, her label, was naturally keen to cement her as a darling of the pop charts. Faithfull, however, had a deep-seated passion for the burgeoning folk scene.

The solution, born of this creative friction, was a remarkable, almost schizophrenic twin release in April 1965: the pop-leaning, self-titled album, Marianne Faithfull, and the entirely acoustic, folk-revival collection, Come My Way. “What Have They Done To The Rain” appears on the former, the ostensibly pop record, but it is stylistically far closer to its folk counterpart. Produced by Tony Calder, with arrangements by the skilled Mike Leander and Jon Mark, the inclusion of this socially conscious, American folk tune on the pop LP speaks volumes about Faithfull’s insistence on staking her claim outside the pure glamour of Swinging London. It’s a quiet declaration of independence nestled between beat covers and French pop chansons.

The song’s subject matter, penned by the great American folk writer Malvina Reynolds, is the dread of radioactive fallout from above-ground nuclear testing, a chilling concern often subtly transmitted through the rain, entering the soil, and tainting the food chain. Reynolds composed it in 1962, and its quiet, desperate poetry had already been championed by artists like Joan Baez.

Sound and Shadow: Unpacking the Arrangement

The production here is masterful in its restraint, particularly when contrasted with the lush, string-laden grandeur of her biggest hits. The arrangement is dominated by a core trio that acts as the backbone: subtle acoustic guitar, a foundational bass part, and a lightly brushed drum kit. The guitar playing, reportedly featuring future Led Zeppelin legend Jimmy Page on some of the album’s sessions (alongside Jon Mark), is a study in texture, offering delicate arpeggios that lend a wistful movement to the track.

The vocal is centered, miked close to capture the ephemeral breathiness that defined her initial sound—a voice that was often criticized, yet possessed an undeniable, haunting fragility. Her phrasing is unhurried, almost narrative, a direct delivery that honors the folk tradition. This clarity of vocal timber is what sells the emotional weight of the song. When she sings of the “old man in the rain with the tears upon his face,” the young woman’s voice sounds utterly exposed, a beautiful artifact perfectly preserved for anyone who invests in premium audio equipment.

The other key sonic element is the piano. It enters with a gentle, almost meditative quality, providing harmonic anchors without ever becoming florid. It’s a mournful counterpoint, its sustain adding a subtle sorrow to the air. The final touch of ornamentation comes from a muted, expressive oboe, its woodwind timbre weeping a simple line in the song’s instrumental break. The overall dynamic is soft, the drums barely breaking the surface, creating an atmosphere that feels less like a studio recording and more like an intimate performance captured in a slightly reverberant, empty church.

It is a simple piece of music, structured around the same two-line lament that opens and closes each verse, yet its quiet power is immense. It forces the listener to lean in, to strain to hear the words that are, in fact, devastating.

Echoes in the Present Day

When I hear this track now, it no longer feels like a relic of the ’60s Ban the Bomb movement. The quiet anxiety it carries has simply shape-shifted.

I think of the young climate activist, staring at a weather map on her phone, the forecast now a source of deep, existential dread rather than mere inconvenience. The line, “The grass is brown and the sun is yellow,” speaks not of Strontium-90, but of endless drought and bleached coral.

I remember once watching a friend of mine, a former activist who’d retired from the street and turned to teaching, sitting quietly, listening to this song while flipping through old black-and-white photos of 1960s marches. The sense of an inherited, perpetual fight against forces too large to see seemed to settle over the room. The fight changes its clothes, but the fundamental question remains: “What have they done?”

“The emotional truth of the protest is found not in the shouting, but in the soft, persistent sorrow of the question itself.”

It’s this contrast—the beautiful, almost ethereal vehicle of the vocal, carrying such a heavy, dark message—that defines Faithfull’s early genius. She wasn’t an overtly political artist in the mold of Dylan or Baez, but her choice to record this particular song at this particular moment in her career was a bold, artful statement. She was using her pop capital to sanctify a piece of the folk revival’s radical core, ensuring this quiet lament reached beyond the coffeehouses and into the mainstream living room. It’s a testament to the enduring power of a simple melody to convey a complicated, devastating truth. The song closes on that sustained oboe note, a single, plaintive cry that hangs in the air, forcing a moment of weighted silence before the next, more frivolous pop track kicks in. It’s a subtle act of musical sabotage, a reminder that even in the brightest sunshine of a new pop age, a shadow remains.

The song is not a nostalgic listen; it is a necessary one. It is a masterclass in how much can be said when an artist chooses to whisper rather than shout, and it continues to resonate with a chilling timeliness.

Listening Recommendations (Adjacent Mood/Era/Arrangement)

- “A Case of You” – Joni Mitchell (1971): Shares the intimate, acoustic guitar and piano arrangement supporting a raw, emotionally vulnerable vocal delivery.

- “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” – Bob Dylan (1963): Another folk piece driven by an arpeggiated acoustic feel, featuring a complex, slightly mournful narrative.

- “They Never Will Leave You” – Marianne Faithfull (1965): A deep cut from the same album, showing her delicate vocal applied to a French piece of music with similar string arrangements.

- “Hush-A-Bye” – Joan Baez (1962): A gentle, early acoustic lullaby that captures the same sense of fragile beauty and stark, unadorned voice as Faithfull’s track.

- “The Sound of Silence” – Simon & Garfunkel (Acoustic Version, 1964): Features that distinct, closely-miked acoustic guitar texture and a somber, reflective mood.