You can almost picture the studio. Two microphones stand in a warm, wood-paneled room, positioned under the watchful gaze of an engineer behind a wide pane of glass. One microphone is for the new king, the man whose steady baritone and unwavering respect for tradition had single-handedly pulled country music back from a pop-infused precipice. The other is for the legend, the survivor, the voice that contained more heartbreak and honky-tonk history than any library could ever hold.

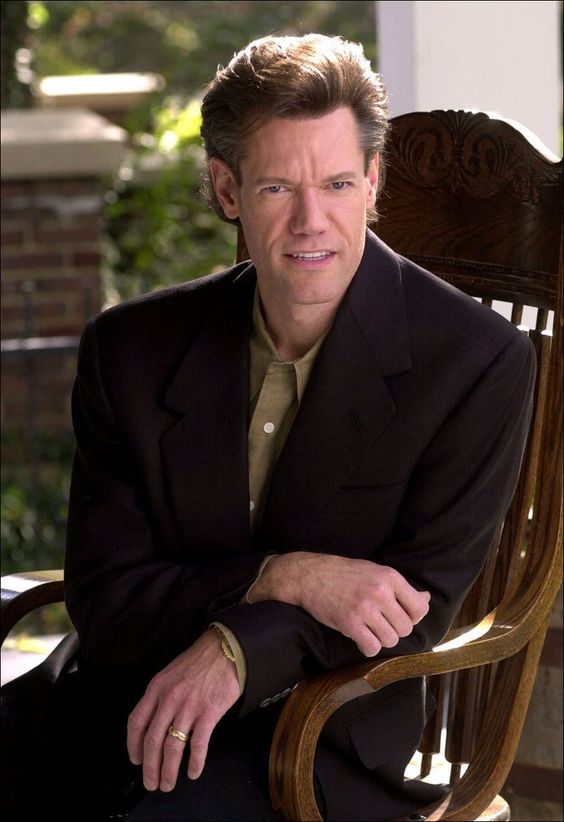

In 1990, Randy Travis was that king. George Jones was, and always will be, “the Possum.” When they stepped up to those microphones to record “A Few Ole Country Boys,” it was more than a duet. It was a summit meeting on tape, a moment where the past and the present of country music shook hands, shared a drink, and agreed that some things are timeless. The result is a recording that feels less like a performance and more like an overheard conversation, brimming with mutual respect and effortless charm.

The track arrived as the lead single from Travis’s fifth studio album, an ambitious project aptly titled Heroes & Friends. The concept was simple and profound: Randy Travis, the biggest star in Nashville, would use his commercial clout to create an entire album of duets with the very artists who had inspired him. It was a gesture of deep reverence, a public thank you note to everyone from George Jones and Merle Haggard to Tammy Wynette and Loretta Lynn.

Produced by Travis’s career-long collaborator, Kyle Lehning, the project was handled with the class it deserved. Lehning’s signature production style—clean, spacious, and deeply respectful of the song and the singer—was the perfect framework for such a historic undertaking. He understood that his job wasn’t to impose a modern sound on these legends, but to create a sonic space where their voices could coexist naturally. For “A Few Ole Country Boys,” this meant crafting a track that was pure, uncut neotraditional country.

The arrangement is a masterclass in understated support. It opens with a classic country flourish: a bright, confident fiddle melody that dances over a shuffling drumbeat and a walking bassline. The steel guitar soon joins, not to dominate, but to answer the vocal phrases with long, mournful sighs. It’s the sound of a thousand Saturday nights in a Texas dancehall, polished just enough for national radio without losing its grit.

The core of the rhythm is a crisp acoustic guitar, strummed with a steadiness that anchors the entire piece. An electric guitar adds subtle, clean licks, punctuating lines and filling spaces with taste and restraint. There is a hint of a honky-tonk piano deep in the mix, not playing solos, but providing a percussive warmth, a gentle harmonic bed that thickens the sound without calling attention to itself. This entire album was built to be heard, and listening back on quality home audio reveals layers of texture Lehning carefully wove together.

But the instruments, as perfect as they are, are merely the stage. The play is the interplay between the two voices.

Randy Travis kicks things off, his voice the very definition of smooth assurance. His baritone is rich and centered, every word delivered with a clarity and sincerity that had become his trademark. He sings his lines straight, setting the scene with a friendly, conversational tone. He’s the narrator, the steady hand, the young man laying out a thesis on the simple virtues of the country way of life.

Then, at the thirty-second mark, George Jones enters. And everything changes.

Where Travis is a sturdy oak, Jones is lightning in a bottle. His voice, weathered by decades of living the very songs he sang, immediately electrifies the track. He doesn’t just sing notes; he bends them, slides into them, and pinches them with that iconic, nasal cry. He phrases with an instinctual, behind-the-beat swagger that no amount of training could ever replicate. When he sings the line, “We’ve been known to get a little loud,” you believe him without a shadow of a doubt.

“It’s the sound of a torch being passed, not with a reluctant sigh, but with a shared grin and a knowing nod.”

The genius of this piece of music is in how Lehning and the vocalists navigate this contrast. Travis never tries to mimic Jones’s wild emotionality. Instead, he holds his ground, providing the anchor that allows Jones to soar. In the chorus, their voices blend in a harmony that is both surprising and deeply satisfying. Travis takes the lower register, a foundational hum of stability, while Jones’s tenor glides over the top, finding pockets of harmony that feel both ancient and spontaneous. To truly appreciate their distinct vocal textures, listen to the separation on a good pair of studio headphones; you can hear every bit of breath and gravel in Jones’s delivery against the pure tone of Travis’s.

The song’s narrative is a simple, proud declaration of identity. It’s about being content with a life of farming, fishing, and old-fashioned values. There’s no deep, hidden metaphor here. Yet, when sung by these two men, it becomes a meta-commentary on country music itself. Travis represents the “new” country boy, the one who remembers and reveres the old ways. Jones is the original, the man who needs no introduction and no justification. The song becomes a dialogue about authenticity, a quiet promise that the traditions are in good hands.

Imagine being a young country fan in 1990. You’ve grown up with Randy Travis on the radio. He’s your hero. This song comes on, and you hear his familiar voice, but then… you hear this other voice. A voice that sounds older, wilder, more unpredictable. You ask your dad who it is, and he smiles. “That’s George Jones,” he says. “That’s the greatest there ever was.” In that moment, the song becomes a bridge, connecting your generation to your father’s, revealing that the music you love has a history as deep and rich as the soil the lyrics praise.

Today, the song evokes a different kind of feeling. In a world of hyper-produced, pop-oriented country, “A Few Ole Country Boys” feels like a transmission from another time. It’s a reminder of the power of simplicity, of what can be achieved when two masters of their craft are given a great song and the space to simply sing it. It’s a warm, comforting sound, the audio equivalent of a well-worn leather chair.

It’s not a ballad of epic sorrow or a tune of foot-stomping revelry. It is something quieter but just as potent: a moment of perfect, unforced camaraderie. It’s the sound of a living legend giving his blessing to the new guard, and the new guard respectfully saying, “Thank you. We couldn’t have done it without you.” The song did well, becoming a top-10 country hit, but its true value isn’t measured on a chart. It’s measured in the warmth it still generates, a testament to the enduring power of two honest voices and one timeless truth. Go back and listen. You’ll hear it, too.

Listening Recommendations

- Merle Haggard & George Jones – “Yesterday’s Wine”: A foundational legend-on-legend duet with a similarly reflective and conversational tone.

- Alan Jackson & George Strait – “Murder on Music Row”: A sharp critique of Nashville’s pop crossover, delivered by two of the era’s neotraditional titans.

- Willie Nelson & Waylon Jennings – “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys”: The quintessential Outlaw duet, capturing a different but equally powerful strand of country camaraderie.

- Brooks & Dunn with Reba McEntire – “Cowgirls Don’t Cry”: A more modern example of a superstar collaboration where distinct vocal styles elevate a shared narrative.

- Brad Paisley & Alison Krauss – “Whiskey Lullaby”: For a darker, more cinematic duet that hinges on the powerful interplay between two unique voices.

- Vince Gill & Patty Loveless – “Go Rest High on That Mountain”: A gospel-infused duet that showcases the sublime beauty of two pure country voices blending in harmony.