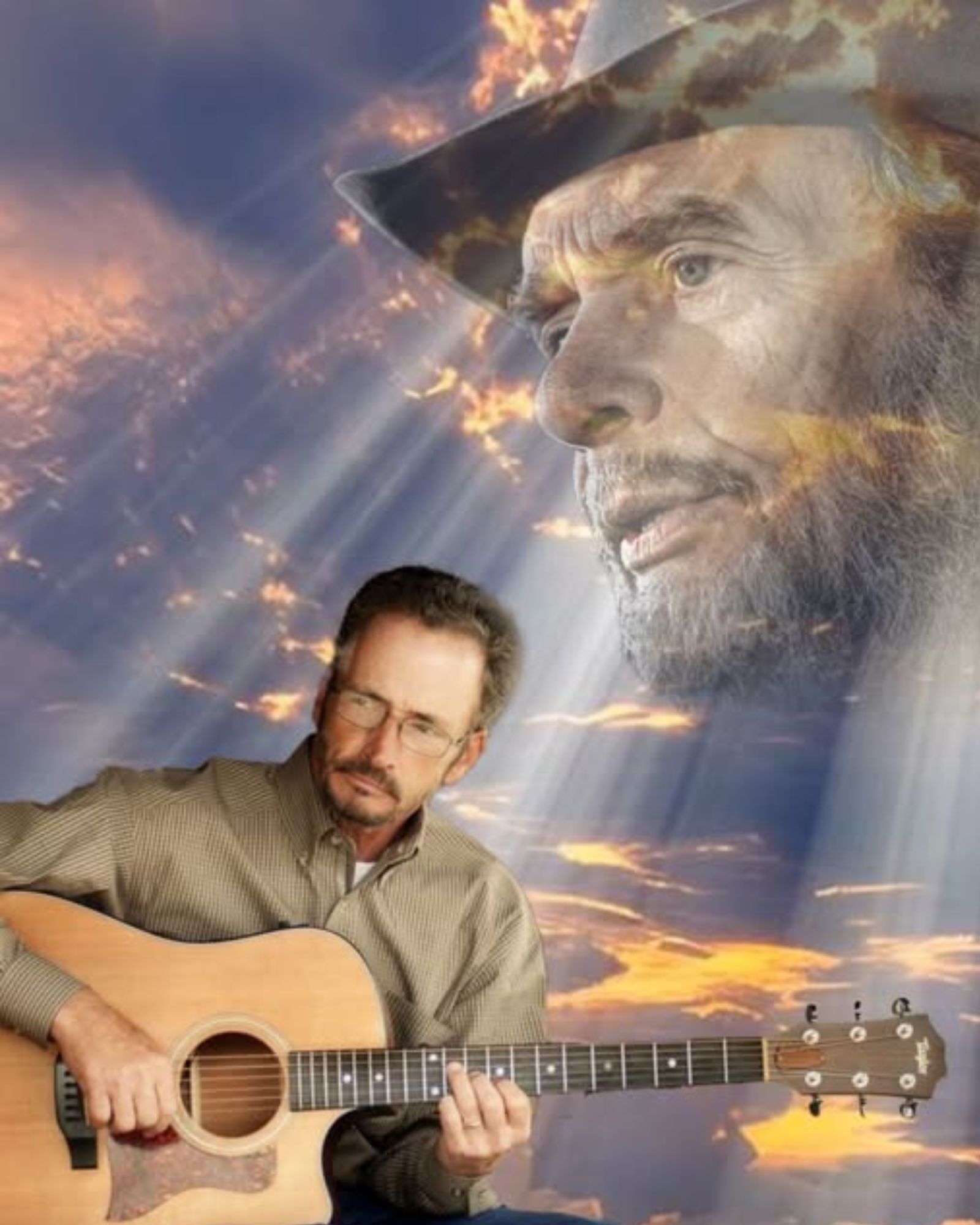

Some songs aren’t just covers; they’re a conversation between a father and son across time. When Marty Haggard picked up the mic to sing his dad Merle’s 1969 classic “Silver Wings,” he wasn’t just performing—he was continuing a legacy. His version is more than a simple reproduction; it’s a “heartfelt testament” to his father’s influence, adding a deeply personal layer of love and admiration that lets you feel the weight of the Haggard name in every single note.

I keep replaying the first ten seconds, not because the notes are elusive, but because of the way the room settles around them. The camera finds Marty Haggard at the Clay Cooper Theatre in Branson, Missouri, and the crowd gives the soft, approving hush that only comes when a familiar title is about to float into the air. This is “Silver Wings,” the Merle Haggard classic that never needed chart fireworks to become permanent. The YouTube caption places the performance on June 21, 2011, a time when Marty was touring a tribute set built from the music he inherited and made his own.

The lineage matters here. “Silver Wings” first appeared on Merle Haggard’s 1969 release A Portrait of Merle Haggard, cut for Capitol Records and produced by Ken Nelson, sitting alongside “Hungry Eyes” and “Workin’ Man Blues.” It was not a single, yet it became one of those songs audiences request with the same certainty they reserve for hits. You can flip through album histories and you’ll keep encountering the same truth: some tracks are less broadcast than bestowed.

If Merle’s studio version felt like the quiet space between departures—a voice at the terminal window counting down to separation—Marty’s 2011 delivery is more like the after-landing, the part where memory replaces scenery. He treats it as a letter you read out loud, not to dazzle, but to honor. Contemporary features on the performance point out the family connection and the song’s original 1969 context; they stress how the ballad earned its status by affection rather than release strategy. That framing aligns with what you hear: a patient, human-scaled reading, nearly conversational in the verses, respectful in the chorus.

The band sets the table with an unfussy country arrangement. In Marty’s Branson-era shows he often worked with a compact ensemble—steel, rhythm section, and lead instruments—which squares with posts from the period that list steel guitar and lead guitar among the chairs. The result on this night is a modest, glowing frame: brushed drums, rounded bass, and those small filigrees from the lead that lift and recede like someone breathing through a story they’ve told before but still feel. Nothing clutters the center; it’s all negative space and clean lines.

The tempo leans slightly behind the heartbeat, and that lag is the song’s courage. Marty gives consonants an extra millimeter of air so vowels can bloom. He lets the reverb trail—just enough to suggest a roomy hall—carry the ends of phrases across bar lines. You can hear the subtle scoops into sustained notes, the controlled vibrato that arrives late like a thought you don’t want to admit. Where some singers might plant a flag at the chorus, he almost folds the melody in his hands as if smoothing a crease.

It works because “Silver Wings” thrives on restraint. As a piece of music, it resists spectacle. The lyric is spatial—metal wings, distance measured in weather and runway light—and so the performance’s job is to hold still while the pictures move past. Marty understands that faithfulness isn’t mimicry; it’s the ability to keep the song’s weather system intact. He avoids the trap of playing to nostalgia for its own sake and instead locates the emotion in the present tense.

Album context clarifies what Marty is protecting. Merle’s 1969 record—made with the Strangers, and guided by Nelson’s light-touch, radio-smart production—documented a band that could make muscular anthems sit beside ballads without strain. The LP carries two stone classics and still finds room for “Silver Wings,” which many sources note was never spun as a single but caught on through the live show and word-of-mouth. Marty’s version feels like a small portal to that era, a chance to measure time not in chart peaks but in how often a song gets asked for after the lights come up.

There’s also the inheritance. Children of icons are tasked with a nearly impossible balancing act: sing the music and step out of its shadow at the same time. Marty threads that needle by leaning into understatement. He doesn’t chase Merle’s burnished baritone; he rides his own grain. On certain lines, he presses a little extra breath across the attack, then relaxes the sustain, letting the band’s gentle backbeat do the carrying. It’s a decision born of lived familiarity—he knows where the emotion sits and doesn’t need to underline it.

You can hear the company he keeps onstage even if the camera mostly favors him. The steel adds a narrow beam of melancholy, sliding into the spaces between chord tones. The acoustic strum keeps the groove glued together while the electric picks out those signature shimmers at phrase ends. When the harmony arrives—barely more than a shadow—it doesn’t crowd; it frames. In 2011, press and fan pages that spotlighted this performance emphasized the familial tribute aspect, but they also celebrated the way the arrangement gave the song room to breathe.

A word about touch. The attack on the lead lines is soft, nearly pad-like—evidence of a player listening for blend rather than dominance. Notes arrive rounded, with the pick easing off just as the steel curls upward. That reciprocal motion—one instrument releasing as the other gathers—creates the sensation of a conversation held in low voices. It’s the difference between nostalgia as decoration and memory as momentum.

I found myself thinking about where this lives in Marty’s career arc. He has long presented music associated with his father, and in places like Branson—the city-as-theatre of American roots nostalgia—those sets become not only concerts but living museums, curated with affection. The 2011 timestamp matters; it situates the show in a decade when country legacies were being reintroduced to younger audiences via clips and reposts. The same upload that documents this performance has quietly kept the memory in circulation, like a reel someone puts on every time the family gathers.

And yet the performance isn’t frozen in amber. Listen closely to the way Marty trims the ends of certain lines, leaving a half-beat of silence before the band breathes. That negative space is modern; it assumes listeners will do the connective work. He trusts the audience to recognize the ache without being spoon-fed. That’s where the performance becomes its own argument.

Sound-wise, the mix captured on the clip is honest: you hear the room’s early reflections and the slight compression on the vocal mic that warms the mids. The bass is kept polite, sitting under the kick rather than thumping against it, which keeps the lyric intelligible. This is not a show built to blast; it’s meant to cradle. If you check it on good studio headphones, you can pick up the tail of the steel’s reverb receding into the hall after the last chorus—a small pleasure worth the restart.

“Even when the notes feel inevitable, the performance leaves just enough air for memory to do the rest.”

Thinking about the original recording session only adds to the gravity. A Portrait of Merle Haggard was a record cut during a ferociously productive run: multiple releases across 1968–70, radio dominance, a band sharpened by the road. That Ken Nelson kept the production spare is significant; he trusted songs and singers to carry themselves. You can hear that aesthetic echoed—through lineage and sensibility—in Marty’s choice to under-sing rather than reach for a shapely climax.

Instrumentation deserves a final glance. The guitar here doesn’t strut; it speaks. A few single-note climbs answer the vocal, then step aside. The steel paints the negative space with half-diminished sighs. If there’s a keyboard in the wings, it stays transparent, reinforcing chords without calling attention to itself. Imagining how the original studio personnel might have handled these colors is instructive—the Strangers were adept at balancing bite and balm—yet Marty’s crew chooses balm almost every time, as if to say the song’s emotion doesn’t require new architecture, only right lighting.

All of this invites a broader reflection on what “Silver Wings” has become. Some songs are era-bound. Others fly on, reinterpreted by family and friends until they feel like standards. This one is the latter. Country outlets that revisit the piece return to the same points—its 1969 origin, its non-single status, its disproportionate fan devotion—and those points function not as trivia but as cultural coordinates. Marty stands at those coordinates and draws a smaller circle. He makes the song sound like someone whispering a goodbye they’ve said before, and—because goodbyes repeat in life—will say again.

Two micro-scenes kept returning to me as I listened.

First: a late-night drive on a two-lane highway, dash lights dimmed. You’re following a tail of red lamps that look like beacons in fog, and the chorus comes around like a thought you can’t chase down. The harmony drops in, you take your foot off the gas, and the chorus drops you right back into that parking-lot farewell, years ago, when you learned that some distances can’t be negotiated.

Second: a kitchen with the radio playing too softly to disturb a sleeping child. You and an old friend are nursing one last coffee. When Marty sings the word that names the wings, your friend nods without looking up. No one says “remember,” because the song does it for you.

There is a dignity to the way this performance declines to overexplain itself. It assumes you know what departure feels like. It assumes you’ve had a runway moment, literal or otherwise. It assumes you’ve watched someone become smaller through glass.

And it’s right.

One more contextual footnote before we close: discussions of the piece often cite Merle’s own account that he shaped it mid-flight with Bonnie Owens—an origin story that suits the lyric’s imagery of air and distance. Whether you take that as anecdote or an artist’s tidy memory, it fits the song’s sense of motion. What matters is that by the time it reached the 1969 LP, it already sounded fully formed. Marty’s rendition, delivered decades later, doesn’t argue otherwise. It simply holds the song to the light and lets us see the miles inside.

If you’re hearing this for the first time, give it three plays. The first to surf the melody. The second to notice how the steel and voice trade glances. The third to sit in the rests between phrases where the story really lives. And if you’re already a devotee, try it through your living-room setup at a conversational volume; the performance rewards the kind of listening where a quiet line can bloom across the room, doing in seconds what long paragraphs cannot. It’s the kind of home audio moment that turns a familiar song into an evening.

Before I leave it, two practical notes for readers who inhabit music from the inside out. If you’re mapping the chordal motion for your own cover, browsing the many versions of the tune’s sheet music can show how different transcribers handle the suspensions in the chorus, which is helpful if you’re arranging harmony. And for singers chasing that poised, unforced delivery, note how Marty keeps the consonants soft and moves the breath early, so the vowel arrives like a gentle landing rather than a lunge.

In the decades since 1969, the song has moved from a track deep in an LP to a hand-to-hand standard carried by families and bands. Marty’s 2011 reading is one more faithful relay in that long pass. It doesn’t reframe or reinvent. It remembers, and in remembering, it renews.

Quietly persuasive? Maybe only this: put it back on. The chorus still takes off, and if you let it, it’ll carry you a little—just far enough to see what you’re leaving and what you might return to.