The day his teenage daughter walked into the studio, nervous, unsure, he handed her a song. A simple story he’d written years ago. Just for fun. But somehow, the words rang different now. She took a deep breath. The tape rolled. And something shifted. When their voices blended—his seasoned, hers bright and unshaped—it wasn’t just a duet. It was a father holding his daughter’s hand, telling her: “I believe in you.” The track made it to radio. Then into homes. Then into hearts. You can still hear it: a father and daughter captured in time, before the world got louder.

I can still hear the hush that falls over a room when “Don’t Cry Joni” begins—the kind of hush you don’t plan, the kind you feel. It’s the soft air of a studio after the engineer cues the tape, when the musicians glance down at music stands and the red light steadies. A breath, then the first glow of the intro: measured, tender, modest in scope. And in that modesty, the record’s power arrives.

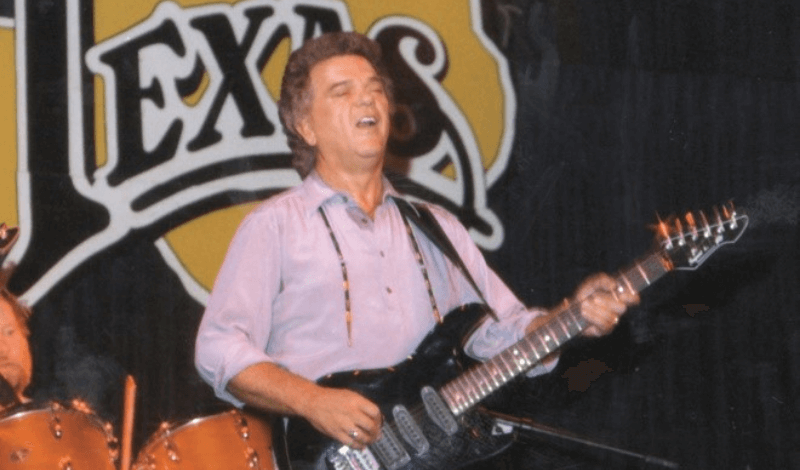

Conway Twitty didn’t need to shout to command attention in 1975. By then he was an institution, radiating the easy authority of a singer who had ridden out the rockabilly years and staked his flag in country. But the grace note on “Don’t Cry Joni” is the decision to share the microphone with his teenage daughter, Joni Lee—an act that changes not only the song’s plotline but its temperature, its resonance, its stakes. The performance asks you to listen more closely because it sounds like a private conversation that we’re gently allowed to overhear.

Historically, the track is anchored to a specific moment. It was issued in 1975 on MCA and produced by Owen Bradley, the architect of so many Nashville touchstones. It appears on The High Priest of Country Music, a release that further consolidated Twitty’s mid-’70s dominance, while also allowing a delicate experiment: a narrative duet that feels intimate and cinematic at once. The single emerged that August; sources document its chart life across country and pop listings, where it became a notable crossover for such a small, unassuming story.

The story itself is plain and potent: a young girl writes to an older neighbor, Jimmy; he returns the letter, gently declining; years pass; the roles reverse; the ending cuts. But what the synopsis misses is how the arrangement makes the plot inevitable. The drummer keeps an even, respectful pulse that feels like a heartbeat in a quiet room. There’s a soft shimmer of strings that doesn’t try to announce itself—just a slow-opening curtain behind the singers. A steel line arcs here and there like the horizon changing color, and you hear Twitty’s voice placed forward, warm and close, as if you could feel the air moving in front of the mic.

And then there is Joni Lee: that tremor of youth, the careful diction, the way she rounds a syllable as though to steady herself. She doesn’t dramatize the character; she inhabits it. Her presence turns the record from a parable into a scene you can place in an actual kitchen—letters on the table, a clock above the door, somebody’s truck idling outside before it pulls away. The duet partners don’t compete; they trade in sincerity. That’s the quiet trick of this recording.

If you sit with the mix, you can map the texture. Acoustic rhythm keeps the frame. A tasteful electric figure—never brash—brushes the edges. A little room reverb gives space but not distance; you can imagine the baffling around the vocalists at Bradley’s command and a careful blend that favors clarity over spectacle. The dynamics rise just enough in each chorus to register a change of mood, then settle back to let the next verse land. Every instrument serves the narrative, and the narrative respects the listener’s intelligence.

As a piece of music, “Don’t Cry Joni” negotiates tenderness and restraint without a single wasted gesture. You hear the arrangement’s architecture: verse, response, and a final twist that reframes every earlier bar. The moral universe is neither punitive nor sentimental; it’s observational. Actions carry weight, timing matters, and love isn’t a puzzle to solve so much as a weather pattern to live through.

There’s also an extra-musical charge that arrives because of who is singing. Father and daughter, sharing a storyline about age difference and delayed recognition—on paper, that might sound awkward. In practice, it becomes something else: a layered performance in which familial trust allows each line to be delivered with more softness than another pair might have mustered. The duet feels guided, protected, and—crucially—judgment-free. The song isn’t wagging a finger; it’s observing two lives that just miss each other’s rhythm.

Twitty’s phrasing remains a marvel. He eases into vowels and resolutely lands his consonants; he enjoys the cadence of a good line without making you aware of technique. There’s nothing labored in how he carries the verses. He’s telling a story he knows will sting and still speaking with kindness. Joni Lee shapes her responses with a melodic profile that suggests hope even as she’s writing the letter that will upend it. The two voices create a corridor that the band threads: not too bright, never muddy, with the bar lines feeling like breaths instead of markers.

Production context matters here. Owen Bradley’s touch is evident in the balance between voices and the unobtrusive polish of the supporting parts. The strings are present but never syrupy; the rhythm section is crisp but never insistent. It’s the Nashville approach he refined for decades: keep the singer in sharp relief and let everything else surround like a halo. The record’s success across charts underscores how compelling that balance was for listeners far beyond country radio in the mid-’70s. Contemporary documentation places its country peak in the upper range while also logging a respectable run on the Hot 100, an unusual path for a hushed narrative ballad.

Consider also how the sound stage manages intimacy. You can envision a single mic each for the leads, bled together just enough to share a little air. When the strings lift behind the second chorus, they rise like a curtain parting rather than a spotlight switching on. The steel curls in without clawing for attention; the acoustic bed is brushed, not strummed hard. This is music engineered to feel like memory—the texture of recall rather than the glare of confrontation.

“Don’t Cry Joni” is not ornate, and that’s the point. In an era that also adored big crescendos and countrypolitan sheen, this record achieves its effect by walking you to a front porch and asking you to listen. What resonates is the echo after each line, the little pauses that signal a character thinking, recalibrating, trying to do right with imperfect timing. The ending lands not as a twist for shock value but as the natural result of years unspooled while two people changed at different speeds.

I return often to the way the record captures the sensation of letters as objects—paper that can be folded, tucked away, carried across distance. You can practically hear the envelope being opened in the silence the band leaves before a verse. There’s a tactile quality to the storytelling: the scrape of a chair, the sound of a screen door, the hum of a small town on a summer evening with the crickets just beginning. These are not literal sound effects, of course; they’re the imagery summoned by a measured tempo, a clear vocal blend, and a band that knows when to step aside.

When I first heard the duet through a good set of studio headphones, the mix revealed still more nuance—the shy push in Joni’s upper notes, the warmth in Conway’s lower register, the little harmonic sheen of the strings placed just off-center. On a well-tuned home audio setup, the bass has a friendly roundness and the brushed percussion breathes rather than taps, keeping the song from ever feeling static. The record rewards quiet attention, not because it hides tricks, but because its craft is the kind you feel in your chest before you name it.

There’s a certain wisdom in how the melody behaves. It rarely jumps; it leans. When the harmony parts enter, they do so to underline rather than argue. That sense of agreement—between arrangement and narrative, between voices and space—gives the performance its calm authority. You don’t need to be a historian to sense the care at work here; the evidence is in how the song makes time slow down long enough for the final line to sting.

Career-wise, the track also speaks to Twitty’s breadth. He had built a run of country hits, many of them grittier or more adult in their themes. Yet here he was, shepherding a quieter tale and using his stature to introduce another voice. Documentation places the single squarely in his productive mid-’70s period under MCA, guided by Bradley’s seasoned hand; it belongs to a sequence of records that set a template for how country could cross into pop consciousness without losing its storytelling soul.

One of the things I admire most is how the record refuses to editorialize. It offers no tidy moral, no scolding, no grand redemption. Instead, it honors cause and effect, letting the calendar do what the calendar does. In that way, the duet feels modern even now. We live with timing, with letters unsent or sent too late, with what we wish we had said becoming the thing we cannot say anymore. The song tucks that realization into a melody you could hum while washing dishes and only later realize what it has done to you.

There’s a practical dimension to why the record plays so well in different rooms. The center image is sturdy; the spectral content is kind; there’s headroom. The vocal blend doesn’t distort at ordinary listening levels, and the transients are brushed so the performance never fatigues. It’s a lesson in how arrangement economics—spend where it counts, save where you can—make a recording age gracefully.

If you’re learning to hear production, listen for how the accompaniment mirrors the plot’s time jumps. The first verse and chorus feel like a fresh letter; the middle sections widen slightly, as if the camera pulls back to show years passing; the final section tightens again—personal, almost whispered. That cinematic framing is achieved with the lightest of touches: a supporting line from the strings, a pick’s brief glide across guitar strings, a chord voiced lower on piano to suggest gravity. Nothing flashy, everything necessary.

“Don’t Cry Joni” is also a reminder that country excels at miniature dramas. The arc is compact, the language familiar, the stakes ordinary; yet the song seems to expand upon playback, filling a room the way memory does—quietly but completely. It also shows how collaboration can be about tone, not just harmony parts. The duet configuration here invites us to weigh two perspectives without forcing a verdict.

Every time I revisit the track, I picture a late afternoon in a small town: sunlight on a mailbox, a gravel road, the smell of cut grass. The recording catches that precise hue of nostalgia—not the kind that polishes everything to a shine, but the kind that holds both sweetness and ache. The final lines aren’t cruel; they’re honest. And the honesty is what lingers.

“Restraint is the record’s boldest instrument—the choice to underplay every emotion until it lands where it matters most.”

There are many reasons the duet has endured, not least its ability to meet listeners at different stages of their lives. As a teenager, you hear longing. In your twenties, you hear the restlessness of moving on. Later, you hear timing’s quiet arithmetic and the cost of chance. The same recording, different mirrors. It’s a rare trick, and it’s pulled off without spectacle.

If you place the track within the broader historical ledger, the facts are straightforward. It was released in 1975, written by Conway Twitty, produced by Owen Bradley, and it charted across country and pop in a way that was striking for such a gentle performance. In some markets abroad it found additional traction later, a testament to the way narrative songs travel. But the vital record of its impact is not on paper; it’s in the hush that still gathers whenever those first bars begin.

And perhaps that is the measure worth keeping. Not the metrics, not the labels, but the lived silence between notes. In that silence, a father and a daughter tell a story about timing, and the story feels true—not because it flatters us, but because it recognizes us. Listen again, quietly, and you’ll hear how the song holds its breath so the ending can speak.

Before I close, a practical note for musicians and listeners who want to sit inside the arrangement: the contours are instructive. Study the vocal entrances, the way the harmony waits a half-beat before entering, the small rise of the strings before the final section. Each decision teaches economy. This is not a record that flaunts technique; it allows technique to disappear into feeling. That’s why it lasts.