The year 1964 was not a year for subtlety. It was the absolute, screaming peak of the British Invasion, a dizzying, joyous blur of Merseybeat’s relentless energy and Mod-sharp attitude. Against this backdrop, where every single seemed to demand immediate dancing or defiant head-shaking, a four-piece band from Blackburn, Lancashire, quietly slipped an elegant, melancholic ballad into the pole position of the UK charts. This was The Four Pennies, and their one week at number one belonged to the hushed, almost pleading sound of “Juliet.”

I remember finding this piece of music buried deep within a forgotten 1960s compilation, a digital fossil on a streaming service’s deep-cut playlist. It came on late one afternoon, a moment of grey drizzle outside my window, and the song’s understated grace instantly cut through the typical archival noise. It was a beautiful, almost disarmingly simple construction, a quiet outlier in a year ruled by The Searchers and Cilla Black.

The Context: A B-Side’s Sudden Ascent

The story of “Juliet” is a classic, mid-century industry tale: a B-side accidentally becomes a hit. Originally the flip to “Tell Me Girl,” the song, co-written by three members—singer Lionel Morton, bassist Mike Wilsh, and guitar player Fritz Fryer—caught the ear of key DJs, leading their label, Philips, to reissue it with the sides flipped. It quickly became their breakthrough, ultimately climbing to the very top of the UK Singles Chart in May 1964.

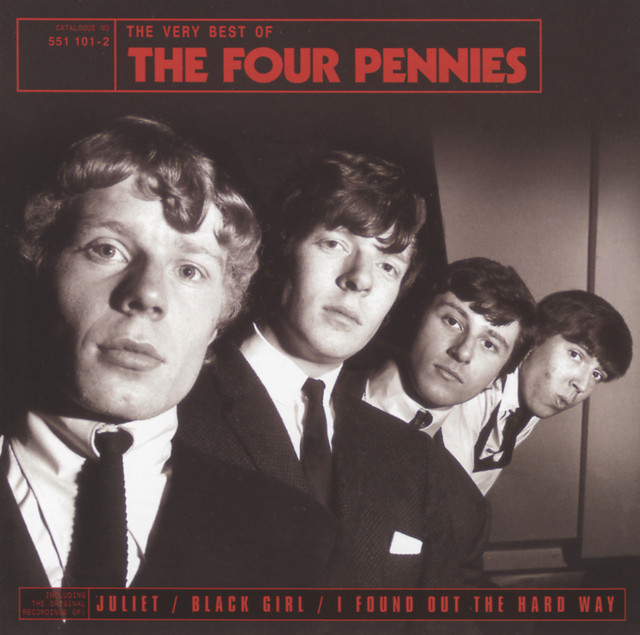

Their career arc, while brief—lasting only until 1966—was defined by this one luminous peak. Before the single, The Four Pennies, originally ‘The Lionel Morton Four’, were a club band signed after a demo caught the ear of renowned producer Johnny Franz (known for his work with Dusty Springfield). They had charted modestly with their debut, “Do You Want Me To,” but “Juliet” was their defining statement. It remains a fascinating snapshot of a group caught between the raw energy of the Beat movement and the polished, orchestral sound of established pop. Their subsequent work included the charting follow-ups “I Found Out the Hard Way” and a folk-blues cover of Lead Belly’s “Black Girl,” showing a versatility that never quite coalesced into a consistent, long-term sound—a common fate in that hyper-competitive era. The band did release one proper studio album in 1964, Two Sides of Four Pennies, though it largely ignored their hit singles, a quaint custom of the time.

The Sound: Restraint and Reverb

The heart of “Juliet” lies in its remarkable arrangement, expertly guided by producer Johnny Franz. It’s a masterclass in economy and melancholy. The song opens not with a guitar riff or a driving drum fill, but with a sparse, almost hesitant introduction. The rhythm section—Alan Buck on drums, Mike Wilsh on bass—lays down a gentle, slow-walking beat, a foundation of quiet resignation. The bass line, in particular, is less a pulse and more a continuous, soft underpinning that gives the song its deep, steady sadness.

The instrumental texture is what truly elevates the track. Morton’s tenor is placed right in the centre of the mix, clean and clear, but his vocal delivery is what sells the mood. He doesn’t belt; he implores, his sound almost a tearful plea that sits perfectly within the song’s modest dynamics. The backing vocals, layered in soft, slightly wavering harmonies on the title phrase, provide a delicate, almost cathedral-like echo, giving the piece an unexpected depth.

The role of the piano is subtle yet crucial. It comes in not as a rock-and-roll staple but as a classic pop instrument, playing simple, descending arpeggios that underscore the sentimentality without ever becoming schmaltzy. It’s the sound of lonely contemplation. The sparse, clean electric guitar lines, likely played by Fritz Fryer, are used less for rhythm and more for colour, adding bright, brief counter-melodies that sound like distant, fleeting memories of happiness.

What truly distinguishes “Juliet” is the gorgeous, almost ethereal reverb on the whole production. It gives the impression of a small, intimate performance taking place in a very large, empty room. The sonic choices reject the garage-band grit of their contemporaries in favour of a restrained, almost pre-rock sophistication.

“It is the sound of an artist choosing quiet dignity over shouting desperation, which, in 1964, was a radical act of restraint.”

This delicate sound has made the song a favourite among collectors and audiophiles. Even decades later, when playing the track on a high-fidelity premium audio setup, the depth of that reverb tail and the warmth of the bass are strikingly clear. It’s a sonic signature, not just a tune.

The Narrative: Nostalgia and Regret

Lyrically, the song is a direct, uncomplicated address to a lost love named Juliet, a clear, classic pop theme. It’s not about angry heartbreak but about the dull ache of a memory that refuses to fade. The songwriting is effective in its concreteness, focusing on simple phrases and a melody that is instantly memorable—a hallmark of great ballad construction. The singer doesn’t rage at the girl who “broke the heart that you gave me,” but merely remembers her, a lingering ghost in the emotional landscape.

This emotional temperature, cool and regretful rather than hot and angry, is perhaps why the song has been historically overlooked in favour of the period’s more visceral hits. It represents a brief, beautiful moment when the Beat Group model embraced the Tin Pan Alley ballad structure, resulting in something uniquely British, melancholy, and understated. Today, a new generation of listeners, tired of compressed, aggressively loud pop, often discovers this track and realizes the simple power of a well-phrased sentiment backed by exquisite, understated arrangement. It’s the perfect soundtrack for a moment of quiet reflection, a personal connection made through the distance of six decades.

The song’s quiet longevity reminds us that sometimes, the moments of greatest cultural significance are not those that shout the loudest but those that whisper directly into the ear.

Listening Recommendations (4–6 similar songs with ONE-line reasons)

- The Walker Brothers – The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore (1966): Similar dramatic, yet controlled, baritone vocal delivery with a lush, melancholic orchestral sweep.

- The Searchers – Needles and Pins (1964): Another early UK Beat group with a softer, more melodic approach and pristine vocal harmonies.

- Gerry and the Pacemakers – Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying (1964): Shares the mid-tempo, sentimental ballad structure and gentle instrumentation from the same era and scene.

- The Bachelors – Diane (1964): Exhibits the same blend of traditional pop vocal style and minimal instrumentation that allowed the sentiment to lead the recording.

- The Zombies – The Way I Feel Inside (1965): For its sparse, piano-driven beauty and profound sense of quiet longing and regret.