The air was perpetually thick with sulfur and ambition in 1967. London was an explosion of color, but beneath the Carnaby Street psychedelia, the old legends still lurked. This was the year that The Herd, a tight, talented group of R&B converts, decided to trade the gritty club circuit for something far grander and stranger. They were chasing the high, dramatic arc of a myth, and they captured it perfectly in a single. This was no mere pop song; it was a Trojan Horse of classicism smuggled onto the UK charts.

The single, “From The Underworld,” arrived in August 1967 on the Fontana label, a dramatic pivot for a band that had been dropped by Parlophone after three unsuccessful attempts at a hit. They were signed to professional songwriting and production duo Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley, men who had found massive success with the charmingly idiosyncratic Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich. Howard and Blaikley, reportedly seeking a more serious artistic outlet, took the tragic love story of Orpheus and Eurydice and translated it into three minutes of pop perfection.

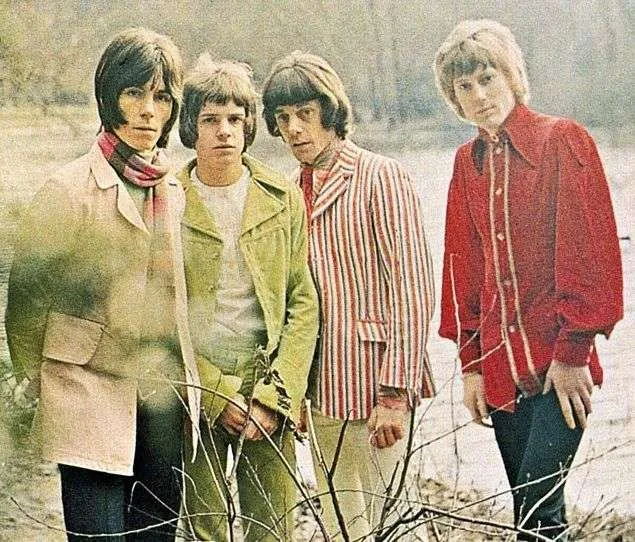

This wasn’t just a hit; it was the breakout for The Herd, peaking at number six on the British singles chart. Crucially, it established the 17-year-old lead singer and guitarist, Peter Frampton, as an instant teen idol—a designation that was both a blessing and a curse. Though Frampton’s destiny would lead him far from these baroque pop structures to the stadium rock heroics of Humble Pie and his massive solo career, this single remains the pivotal moment. It is the foundation myth for the myth-maker.

A Cinematic Overture in the Studio

The first sound is the chilling, funereal resonance of a bell, immediately casting the listener into a solemn landscape. This isn’t the jangly optimism of summer-of-love pop; this is the journey to Hades. The piano then enters, not with a rock-and-roll boogie, but with a stately, almost neo-classical figure. It is crisp and dry in the mix, setting a tense rhythm against the spacious reverb of the introductory soundscape.

The initial impression is one of restraint, a quiet dramatic tension that belies the full-throttle production that’s about to follow. When Peter Frampton’s vocal begins, double-tracked for a haunted, youthful fullness, the arrangement swells instantly, revealing its true complexity. We are immediately presented with a dense, lavish sonic environment crafted by producer Steve Rowland.

The arrangement is a masterclass in mid-60s orchestral pop, an almost baroque-pop maximalism. A full string section is deployed to provide the mournful sweep of a Greek tragedy, sawing and sweeping in great, dramatic movements that underscore the lyric’s descent. Brass cuts through the texture, not to blare a fanfare, but to add a weight of heavy, bronze-age gravity. This dense sound makes one wonder how the four-piece band—Frampton, Andy Bown on organ/keys, Gary Taylor on bass, and Andrew Steele on drums—ever attempted to replicate this intricate piece of music live.

The Sound of Star-Crossed Fate

The emotional center of the track is Frampton’s voice and his guitar. His playing here is far from the sustained, talk-box lead lines that would define his later career. Instead, the guitar work is sharp, punctuating the orchestral sweep with sudden, distorted interjections, almost like a rock counterpoint to the classical instrumentation. There are moments where the fuzz-toned attack feels almost disruptive, a rock energy barely contained by the sophistication of the arrangement. This contrast is the song’s brilliance: the glamour of the orchestra meeting the grit of the burgeoning psychedelia.

Lyrically, the song follows Orpheus’s heartbreaking mission to retrieve Eurydice, walking back to the world of the living with the fatal caveat: he must not look back. The tension of that narrative is mirrored in the dynamic structure. The verses are controlled, driven by the steady drum pattern and bass line, while the chorus opens up into an emotional, soaring cry.

“From the underworld / She’s coming back to me / From the underworld / But I must not look and see.”

The backing vocals are key, layered in a choral style that adds to the epic scale. They sound less like a contemporary pop harmony and more like a Greek chorus, a collective voice of warning and fate. This commitment to the mythological theme—right down to the heavy, almost suffocating atmosphere of the recording—is what elevates the song beyond standard teen-pop fare. It’s a genuinely thoughtful interpretation of a timeless story, wrapped in an undeniably catchy melodic shell.

A Prelude to Superstardom

For a moment in 1967, The Herd seemed poised to be one of the UK’s defining bands. They followed “From The Underworld” with the similarly ambitious “Paradise Lost,” which continued the blend of orchestral drama and pop sensibility, and then the chart-topping “I Don’t Want Our Loving to Die.” However, the pressures of being a ‘singles’ band, coupled with Frampton’s burgeoning, uncomfortable teen idol status—he was dubbed “The Face of ’68″—caused a rift.

The band never quite translated their single success into a cohesive album statement during their peak. Their first full-length, Paradise Lost, largely compiled their singles and B-sides, revealing the uneven mix of crafted pop hits and original R&B-influenced rock written by the band (like Bown and Frampton’s “Sweet William”). Frampton’s growing desire to write and play more substantial, rock-focused music clashed with the pop factory structure of Howard and Blaikley. Ultimately, the very success of this baroque pop masterpiece led to the band’s dissolution. Frampton would depart to form Humble Pie, setting his course for rock and roll immortality.

“The song itself is a perfect cultural pivot point, where the clean, melodic precision of the Merseybeat era collides with the dense, artistic ambition of psychedelia.”

Listening to it today, perhaps on a decent set of studio headphones to fully appreciate the complex layering of the mix, the production still sounds vast. It is a dense, high-fidelity sound, almost overwhelming for the era, and it speaks to the ambition of all parties involved: the songwriters, the producer, and the musicians straining at the seams of their pop identity. This is the moment a band, and a star, had to break apart to fulfill their separate destinies.

The Echoes of Orpheus Today

The song’s power continues to resonate because it taps into that universal human desire: the impossible longing to bring back what is lost, the need to defy a cosmic rule. I often think of it when I see younger musicians wrestling with commercial pressures versus artistic identity. The Herd’s story is a tiny tragedy within the larger rock narrative. They made a work of sublime, dramatic beauty, and it was so potent that it shattered the band, freeing its brightest light.

It’s a song for late nights, driving home with the headlights cutting through the mist, feeling the heavy weight of a choice you made that you can’t undo. It’s a reminder that even the most fleeting of pop records can contain the complexity and weight of myth. In the end, Orpheus looked back. Frampton moved on. But the record remains, a magnificent echo from the underworld.

Listening Recommendations

- Procol Harum – “A Whiter Shade of Pale” (1967): Shares the same dramatic, soulful mood and organ-led, classically-influenced psychedelic-pop aesthetic.

- The Moody Blues – “Nights in White Satin” (1967): For a similar deployment of sweeping, cinematic orchestration to elevate a melancholic pop melody.

- The Zombies – “Time of the Season” (1968): Captures the same blend of psychedelic moodiness with perfect, intricate pop structure and vocal harmonies.

- Love Affair – “Everlasting Love” (1967): Another example of a highly orchestrated, dramatic UK hit from the same period with a powerful teenage vocal.

- Scott Walker – “Montague Terrace (In Blue)” (1967): For the stark, cinematic, and slightly dark orchestral pop storytelling that uses dramatic arrangements for emotional depth.

- The Honeycombs – “Have I the Right?” (1964): Also produced/written by the Howard/Blaikley team, showing their earlier knack for distinctive, punchy chart hits.